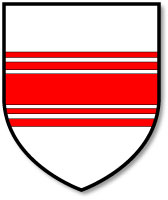

John FitzGilbert (?)1

M, #2641, b. circa 1106, d. b Michaelmas in 1165

| Father* | Gilbert le Marshal2 d. c 1130 | |

John FitzGilbert (?)|b. c 1106\nd. b Michaelmas in 1165|p89.htm#i2641|Gilbert le Marshal|d. c 1130|p482.htm#i14433|||||||||||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | Bride=Aline Pippard3 | |

| Birth* | circa 1106 | Pembroke, Pembrokeshire, Wales4 |

| Divorce* | before 1141 | Principal=Aline Pippard5 |

| Marriage* | 1141 | Bride=Sybil de Salisbury6,7,4 |

| Death* | b Michaelmas in 1165 | 4,5 |

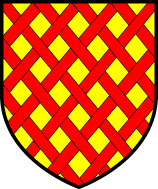

| Title* | Earl of Pembroke1 | |

| DNB* | Marshal, John (d. 1165), marshal, son of Gilbert, marshal of Henry I, first appears in records when, with his father, he successfully defended the family's right to the marshalcy against rivals at some time in Henry I's reign. This plea occurred before 1130, as John was recorded in that year's pipe roll as paying for succession to his father's lands and office. He features by name as master marshal in the Constitutio domus regis, drawn up for Stephen in the early part of his reign, and he seems to have joined King Stephen soon after Henry I's death. He appears constantly in the king's charters between 1136 and 1138, and accompanied the king on his Norman tour of 1137. But there is no trace of him in Stephen's charters after the outbreak of rebellion in the west country. The annals of Winchester say that in 1138 he garrisoned the Wiltshire castles of Marlborough and Ludgershall, which he appears to have had at farm or in fee from Stephen. The king certainly came to regard him as a rebel, because John of Worcester notes that Stephen was conducting a siege of Marlborough when disturbed in September 1139 by news that the empress and Robert of Gloucester had landed in Sussex. In March 1140 a rogue mercenary, Robert fitz Hubert, was captured by John Marshal. The Gesta Stephani says that John Marshal was at this time a member of Gloucester's party, while John of Worcester believed that he was a supporter of the king. It may well be, then, that it was in his own interest that John was working, beginning to define a sphere of lordship in north Wiltshire and the Kennet valley. After the capture of Stephen at Lincoln in February 1141, John appears unequivocally in the empress's following, at Oxford in July and at the siege of Winchester in August and September. He seems to have been that John ‘supporter of the empress’ who, according to the continuator of John of Worcester's chronicle, was detached with a force to prevent the relief of Winchester. He was trapped at Wherwell Abbey which was set on fire around him. The verse biography of his son says that this incident cost him an eye, but is otherwise unreliable on the details. He remained firmly committed to the empress's cause after 1141; his brother, William Giffard, became the empress's chancellor. But his chief preoccupation seems to have been the extension of his power in Berkshire, where the abbey of Abingdon recorded him as one of its chief oppressors, and in Wiltshire, where he came into conflict with Patrick of Salisbury. In 1141 John acted with Patrick's elder brother, William of Salisbury, in the keeping of Wiltshire, but he had fallen out with the Salisbury family by 1145. The Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal preserves a number of stories deriving from this period of private warfare in Wiltshire between two Angevin supporters. However, it cannot disguise John Marshal's ultimate defeat, and the fact that he was forced to come to an agreement with Earl Patrick by which he divorced his first wife, Adelina (who later married an Oxfordshire landowner, Stephen Gay), and married the earl's sister, Sybil. John continued to support the Angevin party, appearing with Henry fitz Empress at Devizes in 1147 or 1149. In 1152 it was the siege of John's forward post of Newbury in Berkshire that provoked the final crisis of Stephen's reign. Under pretext of negotiation, the Marshal (who was not in the castle) surrendered his son William to the king as hostage, but then abused the truce by running provisions and men into Newbury. When informed by the king's messenger that his son's death would follow from this, he is credited with the remark that he still had the hammers and anvil to make more and better sons. As it happened the humane king refused to execute William, and held him at court until the general peace was made the next year. John Marshal remained prominent at Henry II's court in the first year or so of the new king's reign and was allowed to keep most of his gains from Stephen's reign, but it seems that he lost Ludgershall Castle. It probably reflects the general decline in his fortunes that he lost Marlborough Castle in 1158. In 1163 John Marshal was in disgrace; he had indiscreetly disclosed his belief that one of the prophecies of Merlin referred to Henry II and that the king would die before he could return to England. In 1164 John was involved in the persecution of Becket. He had been deprived of the manor of South Mundham in 1162, when the archbishop reclaimed all lands held of him at fee farm. When his suit to regain the manor failed in the archiepiscopal court, he appealed to the king, alleging unfair treatment. Henry II heard the case at the Council of Northampton in October 1164, and although John's case failed, grounds were found to turn the plea against Becket. John Marshal died in 1165, some time before Michaelmas. He was succeeded initially by his eldest sons, Gilbert and John, but the former died before Michaelmas 1166, leaving the entire estate and office of marshal to John, who was succeeded in turn (after 1194) by his younger brother William Marshal, later earl of Pembroke. David Crouch Sources P. Meyer, ed., L'histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal, 3 vols. (Paris, 1891–1901) · Florentii Wigorniensis monachi chronicon ex chronicis, ed. B. Thorpe, 2 vols., EHS, 10 (1848–9) · K. R. Potter and R. H. C. Davis, eds., Gesta Stephani, OMT (1976) · J. Stevenson, ed., Chronicon monasterii de Abingdon, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 2 (1858) · J. C. Robertson and J. B. Sheppard, eds., Materials for the history of Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, 7 vols., Rolls Series, 67 (1875–85) · Ann. mon. · Radulfi de Diceto … opera historica, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 68 (1876) · S. Painter, William Marshal (1933) · D. Crouch, William Marshal (1990) · M. Cheney, ‘The litigation between John Marshal and Archbishop Thomas Becket in 1164’, Law and social change in British history [Bristol 1981], ed. J. A. Guy and H. G. Beall, Royal Historical Society Studies in History, 40 (1984), 9–26 · Pipe rolls © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press David Crouch, ‘Marshal, John (d. 1165)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18122, accessed 23 Sept 2005] John Marshal (d. 1165): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/181228 | |

| Name Variation | John le Marshal3 | |

| Name Variation | John the Marshal6 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1130 | He was with Henry I in Normandy5 |

| Event-Misc | 1137 | He was with King Stephen in Normandy5 |

| Event-Misc | 1138 | He fortified the castles of Marlborough and Ludgershall5 |

| Event-Misc | 1140 | He captured Robert FitzHubert, who had taken the royal castle of Devizes5 |

| Event-Misc | May 1141 | He joined the Empress Maud against King Stephen5 |

| Event-Misc | September 1141 | He was cut off and surrounded in Wherwell Abbey, but escaped with the loss of an eye and other wounds5 |

| Event-Misc | 1144 | "He used his base at Marlborough to raid the surrounding countryside and oppress the clergy"5 |

| Event-Misc | 1158 | Following Henry's succession, he was given lands in Wiltshire, but had to surrender the Castle of Marlborough5 |

| Event-Misc | 1164 | He sued Thomas Becket for part of his manor of Pagham, Sussex5 |

Family 1 | Aline Pippard | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | Sybil de Salisbury b. c 1120 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 55-28.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 66-27.

- [S344] Douglas Richardson, Aline Basset in "Hugh le Despenser," listserve message 14 Apr 2005.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 147.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 81-28.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 66-27.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

Sybil de Salisbury1

F, #2642, b. circa 1120

| Father* | Walter of Salisbury1,2 b. c 1087, d. 1147 | |

| Mother* | Sibilla de Chaworth2 b. c 1082, d. b 1147 | |

Sybil de Salisbury|b. c 1120|p89.htm#i2642|Walter of Salisbury|b. c 1087\nd. 1147|p89.htm#i2643|Sibilla de Chaworth|b. c 1082\nd. b 1147|p135.htm#i4044|Edward of Salisbury|b. b 1060\nd. 1119|p135.htm#i4045|Matilda d' Evereux||p135.htm#i4046|Patrick de Chaworth|b. c 1052|p135.htm#i4047|Maud de Hesding||p135.htm#i4048| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1120 | 2 |

| Marriage* | 1141 | 2nd=John FitzGilbert (?)1,3,2 |

Family | John FitzGilbert (?) b. c 1106, d. b Michaelmas in 1165 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

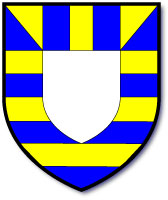

Walter of Salisbury1

M, #2643, b. circa 1087, d. 1147

| Father* | Edward of Salisbury2 b. b 1060, d. 1119 | |

| Mother* | Matilda d' Evereux2 | |

Walter of Salisbury|b. c 1087\nd. 1147|p89.htm#i2643|Edward of Salisbury|b. b 1060\nd. 1119|p135.htm#i4045|Matilda d' Evereux||p135.htm#i4046|Walter d' Evereux|b. s 1034|p148.htm#i4435|Philippa d' Evereux||p140.htm#i4185||||||| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1087 | Salisbury, Wiltshire, England2 |

| Marriage* | Principal=Sibilla de Chaworth2,3 | |

| Death* | 1147 | Chitterne, Wiltshire, England4,2 |

| Burial* | Bradenstock Priory5 | |

| Note | He was the hereditary Sheriff of Wiltshire and Constable of the Salisbury Castle5 | |

| Residence* | Chitterne, Wiltshire, England4 | |

| Name Variation | Walter de Evereux2 | |

| Name Variation | Walter FitzEdward3 | |

| Event-Misc | September 1131 | He was present at The Council of Northampton5 |

| Event-Misc | Easter 1136 | Westminster, He was with King Stephen5 |

| Event-Misc* | before 1147 | Bradenstock, He took the habit of a canon5 |

| Note* | Founder of Bradenstock Priory4 |

Family | Sibilla de Chaworth b. c 1082, d. b 1147 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 27 May 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 81-28.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 108-26.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 66-27.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 78.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 79.

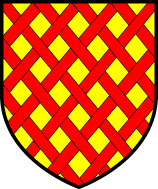

Sir William Marshal1

Sir William Marshal1

M, #2644, b. 1146, d. 14 May 1219

| |

| |

| Father* | John FitzGilbert (?)1,2 b. c 1106, d. b Michaelmas in 1165 | |

| Mother* | Sybil de Salisbury1,2 b. c 1120 | |

Sir William Marshal|b. 1146\nd. 14 May 1219|p89.htm#i2644|John FitzGilbert (?)|b. c 1106\nd. b Michaelmas in 1165|p89.htm#i2641|Sybil de Salisbury|b. c 1120|p89.htm#i2642|Gilbert le Marshal|d. c 1130|p482.htm#i14433||||Walter of Salisbury|b. c 1087\nd. 1147|p89.htm#i2643|Sibilla de Chaworth|b. c 1082\nd. b 1147|p135.htm#i4044| | ||

| Birth* | 1146 | 3,2,4 |

| Marriage* | August 1189 | London, Middlesex, England, Principal=Isabel de Clare3,4,5 |

| Death* | 14 May 1219 | Caversham, England3,2,4 |

| Burial* | Temple Church, London, Middlesex, England3,2,4 | |

| Note* | "He was described as tall and well built, with finely shaped limbs, a handsome face, and brown hair, a model of chivalry in his youger days, and of unswerving loyalty in his maturity and old age."6 | |

| DNB* | Marshal, William (I) [called the Marshal], fourth earl of Pembroke (c.1146-1219), soldier and administrator, was the son of John Marshal (d. 1165) and Sybil (fl. c.1146–c.1156), daughter of Walter of Salisbury. He is one of the few medieval laymen to be the subject of a biography, L'histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal. The biography (here referred to as the History) is in fact an extended poem of over 19,000 lines in rhyming couplets. It was commissioned by William (II) Marshal, the eldest son of the Marshal, and the old Marshal's executor, John (II) of Earley. It is believed that it was written by an expatriate Tourangeau layman, called John, probably in the southern march of Wales at some time in the years 1225–6, before August of the latter year. The writer worked from the memoirs of those who had been witnesses of the Marshal's life, from the recollections of those to whom the Marshal had told stories of his early days, and also from documents in the Marshal family archive. The biography is naturally the principal source for much of what follows here. Upbringing and education, c.1146–1166 William was born the fourth son of John Marshal, the second son by his second wife, whom John had married c.1145 in order to conciliate Patrick, earl of Salisbury, with whom he was engaged in a local war in Wiltshire. The evidence of the History indicates that William was born late in 1146 or early in 1147. In 1152, at the age of five or six, William was offered as hostage by his father, who needed a pledge for a truce with King Stephen, who was blockading John's new castle at Newbury, and who expected the truce to be used to negotiate its surrender. John Marshal, reckless of his son's life, used the truce to provision the castle instead. When challenged that his son would die as a result, he is said to have uttered the notorious response that he did not care about the child, since he still had the anvils and hammers to produce even finer ones. The king made several attempts to convince the indifferent garrison that he would execute the boy, but did not in the end permit it. William seems to have remained at court, more as the king's ward than a captive, until perhaps as late as the settlement of November 1153. He next appears as assenting, with his elder brothers, to his father's grant of the manor of Nettlecombe to Hugh de Ralegh in 1156. It must have been two or three years after this that William was fostered into the household of William de Tancarville, chamberlain of Normandy, who was his mother's cousin. He remained as a squire in the chamberlain's household in Normandy until 1166. Little is known of his training or adolescence, although it is clear from later evidence that he was not put to learn his letters. The only story surviving of this period in his life is that his nickname at Tancarville was Gaste-viande (the Glutton), it being said that when there was nothing to eat, he slept, although the chamberlain predicted great things for him none the less. The household knight, 1166–1182 In 1166, just after his father's death, William was knighted, when he was twenty or thereabouts. His father's testament left him no share of the family lands, which ultimately came to his elder full brother, John Marshal (d. 1194). The chronology of the History is confused at this point, but it seems that after his knighting he became involved in a brief frontier war between Henry II and the counts of Flanders, Ponthieu, and Boulogne, which led to an invasion of the Pays de Caux. The Tancarville household was in garrison at the castle of Neufchâtel-en-Bray, and William found himself in the rare position for a medieval knight of commencing his career in a pitched battle. Apart from a rebuke from his master for being too forward in action: ‘Get back, William, don't be such a hothead, let the knights through!’ (History, ll. 872–4), he distinguished himself in the skirmish. Unfortunately he lost his horse in the cut and thrust of a street fight in the suburbs of Neufchâtel, and failed to take advantage of the opportunity to seize the ransoms that would have retrieved the situation. This was ironically pointed out to him by the earl of Essex, who, at the victory banquet, asked him loudly for various items of saddlery and harness, which he could not produce—but of which he could have had his pick, had he fought professionally, rather than boyishly, in the manner of a knight of the romance. William was confronted immediately after the battle by the problem of the obvious reluctance of William de Tancarville to offer him further maintenance in his household, forcing him to sell his clothes in order to buy a horse to ride. The chamberlain gave him a reprieve when he decided to lead his household to a tournament in Maine, and it was at this point that William Marshal (as he was known long before he inherited the office of royal marshal on his brother's death in 1194—for William and his other brothers Marshal was a surname rather than, or as well as, an occupational title) found his true calling. By the account of the History, the Marshal distinguished himself by capturing a prominent courtier of the king of Scots among others. With the proceeds of his success and the permission of William de Tancarville he threw himself into the tournament circuit for over a year. Late in 1167 or early in 1168 he amicably severed his connection with Tancarville, crossed to England, and took service with his uncle, Earl Patrick of Salisbury. He accompanied the earl to Poitou, where Patrick was given responsibility for the province jointly with Queen Eleanor. William was present at the earl's assassination by a member of the Lusignan family early in April 1168, and was himself cornered by Lusignan soldiers against a hedge, wounded in the thigh by a slash from behind, and captured. He had to undergo a period of uncomfortable captivity, ill from his wound and half-starved by his uncourtly captors. He was eventually released when Queen Eleanor paid his ransom, following which she took him into her retinue. In 1170, following the coronation of Henry, the Young King, in June, William Marshal was transferred into the boy's household to act as his tutor in arms. He was rapidly established as a favourite and infected the boy with his own love of the tournament. He was given responsibility for the organization of the Young King's retinue, and would seem indeed to have acted as his marshal (History gives a wealth of detail about his life on the tournament circuit in the twelfth century, and is indeed the best source for the early history of the tournament). William Marshal is named by Hoveden as one of those who joined the rebellion of the Young King against his father in April 1173. The History asserts that his hero knighted the Young King in the early days of the campaign, but there is some confusion here, for it is known that Henry II himself delivered arms to his son immediately before the boy's coronation in 1170. But the Marshal was certainly with the Young King throughout the period of the rebellion. He was still at his lord's side in October 1174, when he attested the agreement between Henry II and his sons. His attendance on the Young King was constant until 1182. The result of this relationship, together with the rewards of the tournament circuit, was that the Marshal obtained sufficient wealth to maintain his own household knights, and had the resources to raise his own banner at the great tournament of Lagny-sur-Marne in 1180. However, success bred enemies in the Young King's court, and a cabal of William's colleagues succeeded in opening up a gulf between Henry and the Marshal. The principal accusation against him seems to have been that he showed contempt for the Young King in promoting his own interests on the tourney field. A further accusation against him of adultery with Queen Margaret, the younger Henry's wife, would seem to have had little foundation other than in subsequent unsavoury gossip. The two men parted company late in 1182, and an attempt by the Marshal to get redress against his accuser before the Old King at Caen at Christmas 1182 was dismissed. Following this the Marshal went into exile, first making a pilgrimage to the relics of the ‘three holy kings’ in Cologne, and later (apparently) taking service with the count of Flanders, from whom he accepted a large money fee in the city of St Omer. Courtier and magnate, 1183–1189 Increasing difficulties between the Young King and his father in Poitou seem to have persuaded the younger king to take the Marshal back into his service at some time after February 1183, when he began to feel let down by his household. However, the Marshal returned only to witness the last illness and death of his young master (on 11 June near Limoges). The Marshal was at the deathbed and was charged near the end to take the Young King's cloak to Jerusalem to fulfil the vow the king had taken to go to the Holy Land. There were some initial difficulties in accomplishing this. He was seized as security for the payment of their wages by a company of the Young King's mercenaries, and only obtained release with difficulty. After attending the younger Henry's corpse on its troubled journey to burial at Rouen, the Marshal received the permission of Henry II to discharge the obligation laid upon him, and with some financial support from the Old King departed for Jerusalem, after taking leave of his own family in England. William Marshal was in the kingdom of Jerusalem from early 1184 for nearly two years. On his return to Normandy (probably by March 1186) he was received into the royal household. He began to accumulate some of the rewards that went with office. He had a grant of the wardship of the lordship and heir of William of Lancaster soon after his return, and of the royal estate of Cartmel, before July 1188. The Marshal served with distinction in the campaigns against Philip Augustus of France late in 1188, and played a leading part in the last months of the reign of Henry II, as one of the commanders of the royal household guard. He was nowhere more prominent than in the escape of the Old King from Le Mans on 12 June 1189, and was in command of the party that acted as rearguard in the king's flight to Angers. In the course of the action he encountered Richard, the king's son, who was leading the pursuit. Richard was alone and unsupported, having ridden lightly armed ahead of his troops. He is said to have begged the Marshal to spare him, as to kill him would be dishonourable. The Marshal shouted, ‘Indeed I won't, let the Devil kill you, I shall not be the one to do it’, and shifted his lance to kill Richard's horse beneath him (History, ll. 8837–49). After this escape, and a fortnight in garrison at Alençon, the Marshal was recalled to the king in time to witness the conference at Azay and the king's death at Chinon on 6 July 1189. During 1188–9 he was offered marriage first to the heiress of Châteauroux (Berry) and then to the heiress of the honour of Striguil in return for giving up the wardship of the Lancaster lands. He is represented as remonstrating with the seneschal of Anjou that he should open the treasury to give alms to the poor, and as taking responsibility for properly arraying the dead king and escorting him to burial at Fontevrault, but the role the History assigns him may have been retrospectively prominent. None the less, there is no doubt that the heir to the throne, Count Richard of Poitou, was determined to bring William Marshal forward in public affairs on his accession, despite their encounter on the retreat from Le Mans some weeks earlier. The Marshal was confirmed in his possession of Striguil (Chepstow), the honour of the late earl Richard de Clare (Strongbow) (d. 1176) in England and Wales. He married Clare's daughter, Isabel de Clare (1171x6-1220), probably in August following his arrival in London late in July 1189, on what appears to have been a confidential mission to Queen Eleanor, Richard's mother, then at Winchester. In addition to Striguil, by right of his wife the Marshal received half of the Giffard honour of Longueville in Normandy and some Giffard manors (including Caversham) in England. He shared the Giffard lands with the earl of Hertford, who also had a claim to the Giffard inheritance. As well as this, the Marshal's wife brought a claim to the lordship of Leinster, conquered by her father in 1170–71. To consolidate his power in the southern march William Marshal was granted the shrievalty of Gloucester and the keeping of the Forest of Dean. In the service of Richard I, 1189–1199 The Marshal was in constant attendance on the new king from the time of Richard's coronation (in which he carried the sceptre) on 13 September 1189, to his departure on crusade in July 1190. His elder brother, John Marshal, shared in his success, having grants of office and lands. Henry Marshal, a younger brother, was given the deanery of York. So prominent did the Marshal group now appear at court that there is evidence of hostility to it in the actions of Geoffrey Plantagenet, the archbishop of York, and William de Longchamp, the chancellor. The latter acted in the spring of 1190 to remove the shrievalty of York from John (II) Marshal for alleged incompetence, and at the same time moved unsuccessfully to blockade the Marshal's castle of Gloucester, for unknown reasons. William Marshal's star continued to rise, however, for he was made one of the four men appointed by King Richard to monitor William de Longchamp's conduct as justiciar. In October 1191 the Marshal and his fellows co-operated with Count John, the king's brother, in his campaign to remove Longchamp from power, and the Marshal supported the substitution of Walter de Coutances, archbishop of Rouen, as the new justiciar. There was a period of stability when power was balanced between Count John and the justiciars, but that ended in December 1192, when news reached England of King Richard's capture and imprisonment in Germany. The Marshal and his fellows were forced into reluctant confrontation with the count in March 1193. John finally withdrew from England in the summer, and in February 1194, with the king's return imminent, the justiciars acted to confiscate the count's lands in England. In March 1194 the king returned, and at the same time John Marshal died at Marlborough without a legitimate heir (perhaps resisting the justiciars at Marlborough in John's interests, for he was the count's sometime seneschal). This brought William Marshal the family inheritance and completed his landed power base in the west country and southern march. Without waiting to attend his brother's funeral the Marshal joined the royal household on its way to confront John's loyalists at Nottingham, and he played a part in the successful siege of the castle there. However, relations between the Marshal and King Richard were not entirely even. The Marshal refused to do homage to the king for his lands in Ireland, saying that Count John was still his overlord for Leinster. Although the king accepted his reasons, at least one onlooker (William de Longchamp) was brave enough to voice the conclusion that the Marshal was keeping his bridges open to John, as the heir presumptive, saying: ‘Here you are planting vines!’ (History, ll. 10312–26). The Marshal carried a sword of state at King Richard's solemn crown-wearing at Winchester on 17 April 1194. Thereafter William Marshal was closely engaged with the royal court until the very end of the reign, spending much of the period between 1194 and 1199 campaigning in Normandy and elsewhere in northern France. However, he had other tasks. In the early summer of 1197 he was entrusted with negotiations for an alliance between King Richard and the counts of Flanders and Boulogne. In August 1197 he returned to Flanders with Count Baldwin (his lord for a fee in St Omer) and apparently played a prominent part in the action outside Arras in which King Philip was trapped and forced to surrender on terms. He remained very much a military man, and the History has much to say of his campaigns and achievements at this time. For instance, it recalls the active part he played in the taking of the castle of Milly-sur-Thérain, near Beauvais, in 1198, when he climbed a scaling-ladder and defended a section of wall: at that time he was over fifty years of age, but age was not enough to stop him flattening the constable of Milly as he met him on the wall walk. But he did need to sit down on the man's unconscious body, to catch his breath. The Marshal and King John, 1199–1203 While King Richard was dying on 6 April 1199 the Marshal was at Vaudreuil, acting as a ducal justice. There he heard the news of the king's danger, receiving a writ directing him to take charge of the tower of Rouen and secure the city. He heard of the king's death three days later while on the point of going to bed. He crossed the city in the night to discuss the succession with Archbishop Hubert Walter. He declared himself a supporter of Count John for the succession, rather than the king's nephew, Arthur of Brittany, ‘since the son is indisputably closer in the line of inheritance than the nephew is’. Despite the archbishop's warning, ‘that you will never come to regret anything you did as much as what you're doing now’ (History, ll. 11900–6), the Marshal was sent to England with the archbishop to bring his fellow magnates to support John. He then returned to Normandy and joined John's household as it prepared to make the crossing. Immediately before John's coronation (27 May 1199) the Marshal's loyalty was rewarded by investiture as earl of Pembroke. Along with investiture went a promise of Pembrokeshire itself, which the Marshal's late father-in-law had lost to the king in 1154, and which the king still withheld. He had secured the marcher lordship from which he took his title by 1201. It is clear that the Marshal visited the march himself to claim Pembroke late in 1200 or early in 1201. There is strong evidence that, while in west Wales, the Marshal made the crossing to Ireland to visit Leinster and take the homage of his men there, leaving his knight, Geoffrey fitz Robert, behind him as seneschal. He also received once more the shrievalty of Gloucester (lost in 1194) and the keeping of Gloucester and Bristol castles, thus consolidating his power in the south-west of England. He secured for his bastard nephew, John Marshal, son of the late John Marshal (d. 1194), the barony of Hockering in Norfolk, and the lordship of Ryes in Normandy. William Marshal maintained the place at the royal court he had held under Richard in John's first years, and certainly found little cause at this time to regret his choice in 1199, whatever the archbishop is alleged to have warned. He had reached a peak of personal influence and power by 1201, being very close to the new king's counsels. But his career slowly became tainted by the king's failure to maintain his position in northern France. The Marshal had been detailed from 1201 onwards to protect Upper Normandy, but his efforts were increasingly compromised by the king's political misjudgements. At the end of 1203 the Marshal led an unsuccessful attempt to relieve the garrison of the border castle of Château Gaillard, when his energy was defeated by a failure of river-borne and land forces to link up, and his force was decisively defeated by the French commander, Guillaume des Barres. In December 1203 the Marshal accompanied the king on his departure from Normandy for England, after which the duchy fell rapidly to the French invaders. Problems of allegiance, 1203–1206 The loss of Normandy was a serious matter for William Marshal. It had been the theatre for many of his greatest achievements over the past thirty years, and he plainly loved the place. King Philip's conquest of the duchy involved William in serious losses of land, which he was not prepared to let go without more of a struggle than the king was making. When King John sent him and the earl of Leicester to negotiate with the French king in May 1204, the Marshal took the opportunity to open private negotiations about his continued possession of his Norman lands. He and the earl of Leicester paid for a year's grace before they met King Philip's condition of homage for the continued enjoyment of their Norman lands. King John seems to have understood the Marshal's predicament, and was willing to be as obliging as he could to his old ally. In the summer of 1204 he allowed the Marshal to get away with some sharp practice over the Dorset lands of the count of Meulan, which he claimed. He also allowed the Marshal to seek compensation in the southern march of Wales. He granted the Marshal the lordship of Castle Goodrich, and licensed, and perhaps even funded, the Marshal's campaign to recover Cilgerran in Ceredigion from the princes of Deheubarth, which he achieved in December 1204. In spring 1205, however, Normandy was still on the Marshal's mind, and he took advantage of another embassy to do homage to King Philip. From the evidence of the History, King John seems to have been sympathetic to the Marshal's wish to do homage, but was less than pleased when he heard that Philip had prevailed on the Marshal to do liege homage for his Norman lands, obliging the Marshal to do military service to him when in France. This led to a public rift between King John and the Marshal on his return to the English court, for the Marshal refused to accompany him to campaign in Poitou. The king accused him of treason and demanded that the magnates present pass judgment on him, but, remarkably, they refused, perhaps impressed by the Marshal's harangue that they ‘Be on alert against the king: what he thinks to do with me, he will do to each and every one of you, or even more, if he gets the upper hand over you’ (History, ll. 13171–4). The king then attempted to get one of his household knights to challenge the Marshal, but (despite the Marshal's being now nearly sixty) they all refused. None the less, despite this narrow escape, the Marshal had misjudged the situation, and King John decided that he had gone as far as he wished to go in helping the earl of Pembroke recover his losses. The king as a consequence demanded the Marshal's eldest son as a hostage for his faith, and the flood of favours to the earl dried to a trickle. The Marshal was still at court and in November was detailed with other earls to escort King William of Scots from the border south to York. He remained at court nearly until John's departure to Poitou in June 1206, but did not return when the king came back to England in September. In the political wilderness, 1206–1213 From 1206 to 1213 the Marshal spent a biblical seven years in the political wilderness. This would seem to have been (initially) a matter of his own choice, rather than the result of the king's expelling him from court. The king was still well disposed enough towards the Marshal to repay a debt incurred before his departure on campaign. He was even prepared to humour for a while the Marshal's request that he be allowed to cross the sea to his Irish estates, and licences to depart were issued both to him and his principal followers in February 1207. However, he had second thoughts about having a man of the Marshal's prestige trampling about in the lordship of Ireland, which the king seems to have regarded as his own private garden. Messages were sent to the Marshal asking him to hand over his second son, Richard, as hostage for his good behaviour, and also intimating that the king would rather he did not go. But the Marshal was by now determined, and, despite the king's hints, sailed to Ireland with his wife and military household. The king immediately retaliated by relieving the Marshal of his responsibilities in Gloucestershire and the Forest of Dean. The fortress of Cardigan was also taken from him and given to a royal warden. The Marshal was almost immediately drawn into conflict with King John's justiciar, Meiler Fitz Henry, a veteran of the old days of conquest in the 1170s and a willing tool in the king's hand to reduce marcher influence in Ireland. William had already sent his nephew, John Marshal, ahead of him in 1204 to try to assert his interests in Leinster against Meiler, who had laid claim to the region of Offaly. Now he took up the struggle himself. The Marshal would seem to have been the motivating power behind a party of Meiler's enemies, calling itself ‘the barons of Leinster and Meath’, who petitioned the king that Offaly be restored to the lord of Leinster. This the king refused, and demonstrated that he had been told by Meiler who was to blame by promptly recalling the Marshal to England. About 29 September 1207 the Marshal returned to meet the king with only a small escort, leaving his interests in Leinster in the hands of his wife and his household knights. He seems to have expected the worst when he left, and was not disappointed. In the meantime a meeting with the king, Meiler, and a number of Irish barons at Woodstock in October 1207 went singularly badly for the Marshal: many of his former supporters promptly defected to the king with little pressure. Meiler's kinsmen and followers, and a number of the Marshal's own tenants in Leinster, began a military campaign against him in his absence. This was reinforced in January 1208 by Meiler himself, whom the king sent off to Ireland armed with letters of recall to the Marshal's men. Fortunately for the Marshal his military household was up to the challenge, and happy to defy the king. His party negotiated for support with the Lacy family; between them Meiler's men and the rebel knights of Leinster were crushed, and Meiler himself was captured. The countess, William's wife, was more or less left in control of Ireland. Recognizing the inevitable, the king came to terms with the Marshal and restored Leinster to him on new terms, but returned Offaly. Meiler himself was offered as sacrifice to the Marshal, and was in the end disinherited. But the Marshal was certainly no longer required at court, and was allowed (and maybe even encouraged) to leave for Ireland once more. His two elder sons remained hostage in England for his behaviour. The Marshal lived in Ireland in isolation from his former habitat of the court for several years, and amused himself in a reorganization of his lordship there and in some campaigning against the native Irish. He included in his hostilities the native Irish bishop of Ferns, a Cistercian called Ailbe Ó Máelmuaid, who was a friend and intimate of King John from the days when the latter had been count of Mortain. Bishop Ailbe was doubtless persecuted because he had been an ally of Meiler Fitz Henry. The treatment of the bishop of Ferns brought the Marshal under the church's ban by 1216. The only occasion on which the Marshal came into direct contact with the king in his six years' exile from court was in 1210, when he came under suspicion for sheltering the king's enemy, William (III) de Briouze. Briouze had taken refuge in Ireland after falling into disgrace at court, and was briefly entertained by the Marshal in Leinster, before being passed on to his relatives, the Lacy family. The Marshal protested his innocence, crossing over to Pembroke to appear before the king, who was preparing an expedition against the Lacys. He escaped with only a few harsh words and the loss of the fortress of Dunamase, and was sent back across the Irish Sea. Pillar of the throne, 1213–1216 In August 1212 a thaw in relations between the Marshal and the king began, when the Marshal made ostentatious demonstrations of loyalty in Ireland while John was under threat of a baronial conspiracy. The king had perhaps originally suspected the Marshal's involvement, for he had placed his fleet on alert against threats coming from the Marshal's lands, but the king was eventually reassured. The Marshal's elder sons were released into the custody of his friends. Eventually, in May 1213, the Marshal was recalled to the court, where his renowned loyalty was suddenly in demand once more. He was restored to his former position of dominance in south Wales: Cardigan was returned, and the lordships of Carmarthen, Gower, and Haverford added to his responsibilities. He was left virtually justiciar of the march. Following the disaster of Bouvines in 1214 the Marshal was more than ever in demand as mainstay for the royalist cause against the emerging rebel baronial party. The Marshal was chief lay negotiator for the king at London in January and at Oxford in February 1215. When war came despite his efforts, he was sent off to secure the march against the rebels who had allied there with Prince Llywelyn of Gwynedd. Following the king's defeat William Marshal resumed his role of middle man in negotiations with the barons. He may have been assisted—rather than hindered—in this by the defection of his eldest son, William (II) Marshal, to the baronial party at some time in May or June 1215. Far from being a blow to the Marshal, this may have been a deliberate move of father and son (who were devoted to each other) to make sure they had a foot in whichever camp ultimately won; the Worcester annals provide evidence that there was some contemporary suspicion of their motives. This was the sort of game the elder Marshal had already played with his elder brother, John, in 1190–94. For John Marshal had been close to the then Count John, while the Marshal had favoured King Richard. When the crisis came in July 1215 and open war broke out, the Marshal was once again sent off to secure the march and contain the Welsh. Here he stayed while London and the south-east of England fell to the baronial insurgents and Louis of France, in spring 1216. The king's sudden death in October 1216 somewhat retrieved the situation for the loyalist party, and led to the Marshal's greatest political challenge. The Marshal was appointed by King John's last testament as one of a council of thirteen executors to assist the king's sons in the recovery of their inheritance. The assertion by the History that the Marshal was appointed by the king as protector and regent for his son on his deathbed is patently incorrect. However, the Marshal's subsequent actions excuse the mistake. He did indeed start to act the part of regent. He took responsibility for the staging of John's funeral at Worcester Cathedral; convened a council at Gloucester for early November to ratify the arrangements for a protectorship; and took responsibility for the boy king, Henry III, who was brought to Gloucester from Devizes. The only potential rival for the position of loyalist leader was Ranulf (III), earl of Chester, and when Ranulf arrived at Gloucester he made it perfectly clear that he would rather that the Marshal took the lead at that time. The evidence of papal correspondence shows that Earl Ranulf later changed his mind, and was agitating for the Marshal to accept him as coadjutor-regent in the weeks before the battle of Lincoln sanctified the Marshal's rule. Guardian of England, 1216–1219 The Marshal and his royal charge left for Tewkesbury on 2 or 3 November 1216, and thence to another great council at Bristol. At this point his title was decided as ‘guardian [rector] of the king and the kingdom’, a title he first used on 12 November. All royal acts were carried out in his name, and his own seal affixed to chancery writs. He associated with himself the papal legate, Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, who lent his rule not just moral authority, but some legitimacy, England being a papal fief at this time. The Marshal presided over a political stalemate in England until May 1217, but he had the satisfaction of seeing a growing number of barons returning to their allegiance, including his own son, William (II) Marshal, who rejoined him in February. In May 1217 the Marshal led the loyalist column that took first Mountsorrel Castle, Leicestershire, and then moved on to relieve the siege of Lincoln Castle. On 20 May 1217 the Marshal took the field in person, first haranguing his small force and then leading it to the attack against the rebel force at Lincoln, which was commanded by his own first cousin, the count of Perche. He rode into battle with his son, leading the main royalist column that forced an entry into the city through its north gate, while an outflanking force distracted the Anglo-French force by reinforcing the loyalists in the castle. So keen for battle was he that as he was beginning to move his column a page noticed and reminded him that he had not put his helm on. The Marshal (aged about seventy-two) engaged in personal combat in the streets of Lincoln, still able to use his weight and skill as a horseman to force himself deep into the enemy ranks. In the fighting under the west towers of the cathedral he was able to knock from his horse with a sword-stroke Robert of Ropsley, a rebel, who had himself just unseated the earl of Salisbury. There the Marshal witnessed with regret the killing of the count of Perche by a sword splintering through the eyehole of his helm. He supervised the rounding-up of the defeated rebels, and then concentrated his armies on the south-east. It now became the Marshal's chief concern to get Louis of France out of the country with as much decency and haste as possible. The naval defeat of the relieving French force off Sandwich in August proved conclusive. Louis was persuaded to leave London and return to France in return for a general amnesty and an indemnity of 10,000 marks. In later days the Marshal was much condemned for these easy terms, when the French invaders were apparently at the mercy of the loyalists. Maybe the personal embarrassment of having his liege lord's son at his mercy played its part in his policy, but equally well he may have calculated that England needed peace at this time more than anything else. William Marshal held power for nineteen months after the departure of Louis from England. His regime had some successes: the exchequer was re-established and the machinery of the eyre set in motion again. Peace returned to the marches of Wales and an accommodation was reached with Prince Llywelyn of Gwynedd at Worcester in March 1218. The Marshal took full advantage of his opportunities for patronage by furthering his men's interests, most particularly those of his eldest son, who was heavily subsidized out of royal revenues. Mortality caught up with him in January 1219, when he became suddenly ill at Westminster. The symptoms of his last illness suggest a bowel cancer, though this can only be a matter of inference. He was in bed until mid-February, but a remission allowed him to resume the business of government. On 7 March he rode to the Tower of London, but soon fell ill once more. Suspecting his death was upon him, he had himself rowed up the Thames to the former Giffard manor of Caversham in the modern county of Berkshire, opposite Reading, which had become one of his chief residences over the years. He reached his home after three days on the river, and there for a while he carried on in his role of regent; the king was brought to Reading with his tutor, the bishop of Winchester. At a council held in his sick-chamber on 8 and 9 April 1219 he relinquished power to the legate, snubbing the pretensions of Bishop Peter des Roches of Winchester. The Marshal's biography dwells on the events at his deathbed with great detail. A testament was drawn up the day after the Marshal's resignation of power in his own household council, and although a text no longer exists its provisions can be reconstructed. His eldest son, William (II), received the earldom and the bulk of the lands in England, Wales, and Ireland. Richard, his second son, received the Norman lands and the Giffard manors in England. His third son, Gilbert, was a clerk. Walter, the fourth son, received his father's acquisitions: Goodrich Castle and several other English manors. The fifth son, Anselm, was left a large cash legacy, at his father's council's urging. There were other legacies to abbeys and chapter churches in his advocacy, and he left his body to be buried at the New Temple Church in London. He left as his executors David, abbot of Bristol, and his household bannerets, John of Earley and Henry fitz Gerold. The elder Marshal was over a month dying after that, and before the end he was received by the master of the Temple into his order. None the less he was earl of Pembroke to the end, distributing robes from his wardrobe to his household the day before his death, despite the suggestion of a household clerk that he sell them and distribute the cash in alms to the poor. He died in his crowded death-chamber at about midday on 14 May 1219, his head supported by his eldest son, and in possession of a plenary indulgence for his sins. The Marshal's body was laid that afternoon in the chapel of Caversham manor, where it was presumably embalmed. The next day it was taken to Reading Abbey, and lay the night in a side chapel he had financed, in neighbourly fashion. On what must have been 16 May it was borne by wagon to Staines to meet an escort of earls and barons, who accompanied it to Westminster Abbey. At every halt a mass was said, and the funeral exequies were performed, probably on 18 or 19 May, at the New Temple, where the body was laid under a military effigy (one of the first of its type) in the nave. The effigy currently identified as the Marshal's (restored in the nineteenth century, and damaged by a German bomb in the Second World War) has been thought to be his since at least 1661, when the Dutch traveller Schellinks viewed and described it. The corpse did not rest entirely peacefully beneath it. Bishop Ailbe of Ferns (a sometime follower of Count John, later persecuted by the Marshal) caused a scandal by refusing to lift his excommunication from the dead Marshal when brought to the tomb by the king. His curse was said to be responsible for the poor state of the corpse when it was exhumed in the mid-thirteenth century to accommodate building alterations. It was also supposed to account for the extinction of the Marshal line in 1245. The Marshal and the historians The Marshal's immediate posthumous reputation was not as shining as the sponsors of the History had perhaps hoped to establish. Matthew Paris in the next political generation repeated views of him as a figure of some ambiguity, too easy on the French and too harsh to the church. The discovery of a text of the History by Paul Meyer in the sale of the Savile Library in 1861, and its subsequent edition and publication by him, has projected William Marshal into the foreground of modern interpretation of the medieval noble mentality. Modern interpreters have tended to find what they themselves expected. Meyer himself, and Sidney Painter, fulfilled the expectations of the Marshal's executors and saw him as the chivalric hero of his day: taking up the description of him attributed by the History to King Philip of France, ‘the best knight in all the world’. But the Marshal was only one of several contemporaries who were regarded in that light: Guillamme des Barres the elder, and Robert de Breteuil, earl of Leicester (d. 1204), were quite as prominent as warriors and statesmen. Georges Duby dispelled the mythology of the Marshal as a hero of chivalry, but went too far in stressing his physical, animal nature at the expense of his undoubted gifts as a courtier. In fact the Marshal was a military captain of some international repute, and a physically accomplished sportsman and warrior. Principally he was a courtier, and trained to be such from boyhood. He cultivated and practised carefully the deferential and affable behaviour necessary for survival in the retinues of greater men. He was in his mid-forties before he was placed into any situation where a broader political judgement was needed. As one of Richard's appointees to oversee William de Longchamp in 1190–94 he demonstrated an eagerness to offend neither the king nor Count John which showed him to be a political trimmer at heart—compelled by early training to avoid offending anyone powerful—and a self-serving trimmer he always remained. Trimming was behaviour that might be mistaken for sagacity, but in his case it was really no more than caution masking incomprehension. The only thing his vision comprehended was the direction of his own interests, and these he could pursue ruthlessly, and sometimes recklessly as can be seen in his complaints of poor reward to Henry II in 1188. It is unlikely that anyone took him seriously as a political figure of any great weight (as opposed to a military captain) until the reign of John, who (ironically in view of the verdict of the History on him) vigorously promoted the Marshal's political fortunes. It was consistent misjudgement in pursuing his own interests that brought the Marshal down in 1205, and his tired decision to retreat into self-imposed exile in Ireland in 1207 should have been the end of his active career. But King John's own difficulties, the Marshal's undeserved reputation for political wisdom, and his deserved reputation for military success, pulled him out of retirement. His luck was that he was the ideal man for the moment in 1216, and his greater luck was that the moment was not so prolonged as to reveal his political weaknesses. Perhaps, too, by this time his great age made it easier for him to command obedience and respect. William Marshal was very successful as an estate owner and regional magnate. He could be as charming and affable to social inferiors who were of use to him, as to his superiors. There is no doubt that, if let be, behind the courtier and opportunist was a well-disposed and kindly man. However, the Marshal followed his father and the spirit of his age in being remorselessly vengeful to lesser men who opposed his local ambitions, as was seen both in Leinster and south Wales. His closeness to the king between 1189 and 1205 made his service very attractive to the politically mobile class of lesser bannerets and county knights. He created one of the first recognizable regional political affinities, basing his power in the south-west of England and southern march of Wales. This affinity in turn enhanced his position at court. King John made great use of the Marshal's local power base in his difficulties with rebels. The Marshal's ecclesiastical patronage was conventional for a magnate of his day. He was a generous patron of the regular orders: he greatly favoured the templars; he founded an Augustinian priory at Cartmel about 1189, and the Cistercian houses of Duiske and Tintern Parva in Leinster in the first decade of the thirteenth century. He was survived by his wife, Isabel, for less than a year: she died at Chepstow in February 1220, and was buried at Tintern Abbey. They left five sons: William (II), Richard Marshal, Gilbert Marshal, Walter Marshal, and Anselm Marshal [see under Marshal, William (II)], successive earls of Pembroke. They also had five daughters: Matilda, who married successively Hugh Bigod, earl of Norfolk, and William (IV) de Warenne, earl of Surrey, Isabel, who married successively Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester and Hertford, and Richard, first earl of Cornwall; Sybil, who married William de Ferrers, earl of Derby; Eve, who married William (V) de Briouze; and Joan, who married Warin de Munchensi. David Crouch Sources P. Meyer, ed., L'histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal, 3 vols. (Paris, 1891–1901) · A. Holden, S. Gregory, and D. Crouch, eds., The history of William Marshal, 3 vols., Anglo-Norman Texts [forthcoming] · S. Painter, William Marshal (1933) · G. Duby, William Marshal: the flower of chivalry, trans. R. Howard (1984) · D. Crouch, William Marshal (1990) · GEC, Peerage, new edn, 10.358–64 · The journal of William Schellinks' travels in England, 1661–1663, ed. M. Exwood and H. L. Lehmann, CS, 5th ser., 1 (1993) · Ann. mon., vol. 4 · Chronica magistri Rogeri de Hovedene, ed. W. Stubbs, 2, Rolls Series, 51 (1869) · N. Vincent, ‘William Marshal, King Henry II and the honour of Châteauroux’, Archives, 25 (2000), 1–15 Likenesses tomb effigy, Temple Church, London [see illus.] © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press David Crouch, ‘Marshal, William (I) , fourth earl of Pembroke (c.1146-1219)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18126, accessed 23 Sept 2005] William (I) Marshal (c.1146-1219): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/181267 | |

| Name Variation | William le Marischal2 | |

| Occupation* | Marshal of England3 | |

| Event-Misc | 1152 | He was given by his father as hostage to King Stephen, but was spared by the king, despite his father's rebellion8 |

| Event-Misc | between 1159 and 1167 | He squired for William de Tancarville, hereditary Master Chamberlain of Normandy8 |

| Event-Misc* | 27 March 1168 | Poitou, William was wounded and captured in an ambush while serving for his uncle Patrick (who was killed at that time)., Principal=Patrick d' Evereux8 |

| Event-Misc | He was ransomed by Queen Eleanor, and was chosen by King Henry II to be a member of the Young Henry's household.8 | |

| Knighted* | 1173 | Drincourt, by William de Tancarville8 |

| Event-Misc | He supported Young King Henry in his rebellion against his father8 | |

| (Witness) Knighted | by William Marshal, Principal=Henry of England8 | |

| Event-Misc* | 11 June 1183 | On his deathbed, Young King Henry charged William Marshal to carry his cross to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, which he subsequently did, Principal=Henry of England8 |

| Event-Misc | 1187 | On his return to England, he was made a member of the Household of Henry II8 |

| Event-Misc | from 1188 to 1189 | He served King Henry in France against his rebelling sons, once stopping Richard's pursuit by killing his horse (rather than Richard, which he could have). He was with Henry II to the last and escorted his body to Fontevrault for burial.8 |

| (Witness) King-England | 3 September 1189 | Westminster, Middlesex, England, Principal=Richard I the Lionhearted9,10,11,12 |

| Event-Misc | 1189 | King Richard gave him Isabel de Clare in marriage and a number of posts for his service8 |

| Event-Misc | October 1191 | When the Archbishop of Rouen succeeded Longchamp as Justiciar, William became his chief assistant8 |

| Event-Misc | 1193 | When Prince John revolted against King Richard, William besieged and took Windsor Castle.8 |

| Event-Misc | between 1194 and 1199 | He was in Normandy for the King13 |

| Event-Misc | 1199 | Upon Richard's death, William supported King John, and obtained support of the nobles at a meeting in Northampton13 |

| (Witness) Crowned | 27 May 1199 | Westminster Abbey, Westminster, Middlesex, England, King of England, Principal=John Lackland14,5,9,11,15,16 |

| Title | 27 May 1199 | Earl of Pembroke17,13 |

| Event-Misc | 20 April 1200 | He was confirmed Marshal of England13 |

| Event-Misc | 1204 | He invaded Wales and captured Kilgerran13 |

| Event-Misc* | 1205 | Robert de Tregoz made a trip to the continent with William Marshal, Principal=Sir Robert de Tregoz18 |

| Event-Misc | June 1205 | He joined the Archbishop of Canterbury in forcing King John to abandon a projected expedition to Poitou13 |

| Event-Misc | between 1207 and 1211 | He spent most of his time in Ireland13 |

| Event-Misc | April 1213 | He was recalled by King John13 |

| (Witness) Event-Misc | 15 May 1213 | John agreed to reconcile with the Pope, becoming the Pope's vassal. The interdict and excommunication were lifted., Principal=John Lackland11,13 |

| Event-Misc* | 1214 | He was commander in England while John was absent in Poitou13 |

| (King) Magna Carta | 12 June 1215 | Runningmede, Surrey, England, King=John Lackland19,20,21,22,23,24 |

| Title* | between 1216 and 1219 | Regent of the Kingdom3 |

| Event-Misc | 11 November 1216 | Bristol, He was chosen unanimously to be regent for Henry III13 |

| Event-Misc* | 11 September 1217 | William Marshal concluded the Treaty of Lambeth with Prince Louis, Principal=Louis VIII "le Lion" of France13 |

| HTML* | National Politics Web Guide |

Family | Isabel de Clare b. 1173, d. 1220 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 81-28.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 66-27.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 145-1.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 16.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 149.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 147.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 2.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 2.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 3.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 79.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 148.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 1-26.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 29.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 84.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Wales 4.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 245.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Longespée 3.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 3.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 56-27.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 60-28.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 8.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 34.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 127-30.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 149-2.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 38.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 69-28.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 148-1.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 63-28.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 145-2.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 80-27.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 146-2.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Mortimer 6.

Gervase Paynel1

M, #2645, d. 1194

| Father* | Ralph Paynel1 d. b 1153 | |

| Mother* | (?) Ferrers1 | |

Gervase Paynel|d. 1194|p89.htm#i2645|Ralph Paynel|d. b 1153|p86.htm#i2557|(?) Ferrers||p86.htm#i2558|Fulk Paynel||p86.htm#i2562|Beatrice FitzWilliam||p86.htm#i2563|Robert Ferrers|b. c 1076\nd. 1139|p86.htm#i2559|Hawise of Vitré|b. c 1086|p86.htm#i2560| | ||

| Marriage* | 2nd=Isabel de Beaumont2 | |

| Death* | 1194 | 3 |

| Last Edited | 1 May 2005 |

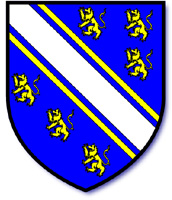

Sir Edward le Despenser K.G., M.P.1

M, #2646, b. 24 March 1335/36, d. 11 November 1375

| |

| Father* | Sir Edward le Despenser2,3,4 d. 30 Sep 1342 | |

| Mother* | Anne de Ferrers2,5 d. 8 Aug 1367 | |

Sir Edward le Despenser K.G., M.P.|b. 24 Mar 1335/36\nd. 11 Nov 1375|p89.htm#i2646|Sir Edward le Despenser|d. 30 Sep 1342|p90.htm#i2673|Anne de Ferrers|d. 8 Aug 1367|p90.htm#i2674|Sir Hugh le Despenser|d. 24 Nov 1326|p69.htm#i2057|Eleanor de Clare|b. Oct 1292\nd. 30 Jun 1337|p69.htm#i2058|Sir William de Ferrers|b. 30 Jan 1271/72\nd. 20 Mar 1324/25|p90.htm#i2675|Ellen de Segrave||p90.htm#i2680| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | 24 March 1335/36 | Essendine, Rutland, England1,6,7 |

| Marriage | before 2 August 1354 | Principal=Elizabeth de Burghersh6,7 |

| Marriage* | before December 1364 | Conflict=Elizabeth de Burghersh8,3,9,10 |

| Death* | 11 November 1375 | Llanbethian, Glamorgan, Wales8,3,6,7 |

| Burial* | Tewkesbury Abbey, Gloucestershire, England6,7 | |

| DNB* | Despenser, Edward, first Lord Despenser (1336-1375), magnate and soldier, was born at Essendine, Rutland, on 24 March 1336, the son and heir of Sir Edward Despenser (d. 1342)—the second son of Hugh Despenser the younger (d. 1326)—and his wife, Anne (d. 1367), the daughter of William, Lord Ferrers of Groby. Henry Despenser was his brother. From his father, who died in 1342, Edward Despenser inherited substantial estates, including nine manors, mostly in the midlands, and in 1349 he succeeded his childless uncle, Hugh, second Lord Despenser (of the first creation), in the principal estates of the family. A profitable marriage was arranged, probably in 1346, between Despenser and Elizabeth (d. 1409), granddaughter of Bartholomew Burghersh, the elder (d. 1355), a wealthy magnate who was the king's chamberlain. Elizabeth was the sole heir of her father, the younger Bartholomew Burghersh, and his first wife, Cecily Weyland. This marriage, which took place before 2 August 1354, ultimately enabled Despenser, after his father-in-law's death in 1369, to acquire his wife's valuable estates, which comprised ten manors in Suffolk and half of the Welsh marcher lordship of Ewias Lacy. Throughout Edward Despenser's minority the greater part of his lands was administered by his kinsfolk and officials on his behalf. After dower had been assigned to Hugh's widow, Elizabeth, the residue of the Despenser estates was farmed, on 8 February 1350, to Bartholomew Burghersh, the elder, and the young heir, for the probably undervalued sum of £1000 a year. This custody was subsequently transferred to the Despenser heir and his mother, Lady Anne, on the same terms. Although he came of age in 1357, Edward Despenser did not have full possession of his family inheritance until after the death of the dowager, Elizabeth, in 1359. Despenser's military career began before his coming of age in March 1357. With his father-in-law, Lord Burghersh, he was in the retinue of the Black Prince on his first expedition to Gascony in 1355, and he fought at Poitiers on 19 September 1356, when the French king, John II, was captured. He was still in Gascony in March 1357, and he probably returned to London with the prince of Wales during the following month. He was summoned to parliament in December 1357. When Edward III invaded France for the last time in October 1359, Despenser was one of the English magnates who served with the king, and he was still in France two years later. In 1361 he was made a knight of the Garter and given the stall next to the king's in St George's Chapel, Windsor. Meanwhile the treaty of Brétigny, made in May 1360, had ended the most profitable phase of the French war. Although Despenser was one of the Irish landowners who were commanded in February 1362 to go to Ireland to assist the king's third son, Lionel, to restore order in that land, it seems unlikely that he left England again until 1368. He was present in London when Lionel was created duke of Clarence on 13 November 1362, and it was in his service that he later enlisted. Despenser was the most important of the followers who accompanied Duke Lionel on his journey to Milan to marry Violante Visconti in May 1368, and he remained in Italy for over four years. After Lionel died suddenly on 17 October 1368, Despenser believed that his patron's death had been brought about by poison, and in revenge he took service with the pope, Urban V, in his war against the Visconti of Milan. On 10 March 1370 the pope wrote to John of Gaunt commending Despenser, who had won a great reputation by his prowess in battles in Lombardy. Despenser's prolonged sojourn in Italy appears to be commemorated in the fresco of the church militant and triumphant painted by Andrea da Firenze (Andrea Bonaiuti) and others in the Spanish chapel of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. This fresco depicts the meeting at Viterbo of Urban V and the emperor, Charles IV, on 17 October 1368; conspicuous in the group standing near the emperor is a knight of the Garter, clad in white, gold-embroidered garments. This figure, which portrays in profile a good-looking man with a short, reddish, pointed beard, has been identified as Edward, Lord Despenser, who was the only knight of the Garter in Italy at that time. If this identification is correct, he was the first Englishman to be portrayed in Italian art since Thomas Becket. Despenser's exploits in Italy made him a renowned hero of chivalry. Froissart, who knew him personally and benefited from his patronage, eulogizes him as the most handsome, most courteous, and most honourable knight of his time in England, and relates that it was at the request of John of Gaunt that Despenser returned home in the summer of 1372. He was constable of Gaunt's army in the great chevauchée of 1373, when Gaunt marched across France from Calais to Bordeaux, losing half his troops on the way. The Breton expedition in the spring of 1375 was the last successful English undertaking in France in the late fourteenth century; Despenser, in company with Edmund of Langley, earl of Cambridge (afterwards duke of York), and Edmund Mortimer, earl of March, was attacking Quimperlé when this campaign was cut short by the truce of Bruges. After his return home Despenser visited Cardiff in September 1375; he died a few weeks later at his manor of Llanblethian, near Cowbridge, on 11 November, aged thirty-nine. His effigy on his tomb in Tewkesbury Abbey shows him in full armour, kneeling in prayer. His death was followed by another prolonged minority, since his surviving son, Thomas Despenser, was only two years old when his father died. The Despensers were an unlucky family; if Edward Despenser's career had not been prematurely cut short, his knightly prowess might well have earned him promotion to an earldom, a rank merited by his great landed possessions and his prestige as a famous military hero. T. B. Pugh Sources Adae Murimuth continuatio chronicarum. Robertus de Avesbury de gestis mirabilibus regis Edwardi tertii, ed. E. M. Thompson, Rolls Series, 93 (1889) · Œuvres de Froissart: chroniques, ed. K. de Lettenhove, 25 vols. (Brussels, 1867–77) · CEPR letters, vol. 4 · Dugdale, Monasticon, new edn · W. Dugdale, The baronage of England, 2 vols. (1675–6) · H. J. Hewitt, The Black Prince's expedition of 1355–1357 (1958) · G. Williams, ed., Glamorgan county history, 3: The middle ages, ed. T. B. Pugh (1971) · GEC, Peerage · G. Andres, J. M. Hunisak, and J. R. Turner, The art of Florence (1988) · M. A. Devlin, ‘An English knight of the garter in the Spanish chapel in Florence’, Speculum, 4 (1929), 270–81 · A. Gardner, English medieval sculpture, rev. edn (1951) · G. B. Parks, The English traveler to Italy (1954) · CIPM Likenesses A. da Firenze and others, fresco, c.1368, Spanish chapel of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy · effigy, Tewkesbury Abbey, Gloucestershire © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press T. B. Pugh, ‘Despenser, Edward, first Lord Despenser (1336-1375)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7550, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Edward Despenser (1336-1375): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/755011 | |

| Name Variation | Despencer7 | |

| Event-Misc | 1349 | Edw. le Despenser was heir to his uncle, Hugh le Despenser, 3rd Lord le Despenser, Principal=Sir Hugh le Despenser7 |

| Event-Misc | September 1355 | accompanied the Prince of Wales to Gascony6,7 |

| Event-Misc | 19 September 1356 | He fought at the Battle of Poitiers7 |

| Summoned* | between 15 December 1357 and 6 October 1372 | Parliament6,7 |

| Event-Misc* | from 1359 to 1360 | He took part in the invasion of France7 |

| Knighted* | 1361 | He was nominated K.G.12 |

| Event-Misc | 1368 | He went with Lionel, Duke of Clarence, to Milan. He subsequently was in the service of Pope Urban in his war against the Viscount of Milan, winning a great reputation in battles in Lombardy7 |

| Event-Misc | 1372 | He returned to England at the request of John of Gaunt7 |

| Event-Misc | from 1373 to 1374 | He was Constable of the Army of John of Gaunt in France7 |

| Event-Misc | 1375 | He assisted the Duke of Brittany in his campaign there.7 |

| Title* | 4th Lord le Despenser, Lord of Glamorgan and Morgannwg, Wales, and, in right of his wife, of Ewyas Lacy, Herefordshire8,7 |

Family | Elizabeth de Burghersh b. 1342, d. c 26 Jul 1409 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 81-27.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 74-33.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 14-8.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Clare 10.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 14-7.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Clare 9.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Despenser 9.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 70-35.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Ferrers 10.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 43.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 84.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 13-9.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Ferrers 11.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 14-9.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Clare 8.

Elizabeth de Burghersh1

F, #2647, b. 1342, d. circa 26 July 1409

| Father* | Sir Bartholomew de Burghersh K.G.2,3,4,5,6,7 b. s 1323, d. 5 Apr 1369 | |

| Mother* | Cicely de Weyland8,4,6 b. c Apr 1319 | |

Elizabeth de Burghersh|b. 1342\nd. c 26 Jul 1409|p89.htm#i2647|Sir Bartholomew de Burghersh K.G.|b. s 1323\nd. 5 Apr 1369|p89.htm#i2648|Cicely de Weyland|b. c Apr 1319|p89.htm#i2649|Sir Bartholomew de Burghersh|b. c 1304\nd. 3 Aug 1355|p89.htm#i2652|Elizabeth de Verdun|b. c 1306\nd. 1 May 1360|p89.htm#i2651|Sir Richard de Weyland|b. c 1290\nd. b 8 Oct 1319|p89.htm#i2650|Joan (?)||p477.htm#i14287| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | 1342 | 1,3,4,9 |

| Marriage | before 2 August 1354 | Principal=Sir Edward le Despenser K.G., M.P.4,9 |

| Marriage* | before December 1364 | Conflict=Sir Edward le Despenser K.G., M.P.2,10,11,7 |

| Death* | circa 26 July 1409 | 2,3,4,9 |

| Burial* | Tewkesbury Abbey, Gloucestershire, England4,9 | |

| Event-Misc* | between 1382 and 1387 | She sold the manors of Heytesbury, Colerne, and Stert, Wiltshire, to Thomas Hungerford.9 |

| Will* | 1409 | bequeathing two chargers and twelve dishes of silver to daughter Margaret, Witness=Margaret le Despencer12 |

Family | Sir Edward le Despenser K.G., M.P. b. 24 Mar 1335/36, d. 11 Nov 1375 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 5 Feb 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 81-27.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 70-35.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 13-9.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Clare 9.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Ferrers 11.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Burghersh 10.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 43.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 70-34.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Despenser 9.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 14-8.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Ferrers 10.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Ferrers 8.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 14-9.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Clare 8.

Sir Bartholomew de Burghersh K.G.1

M, #2648, b. say 1323, d. 5 April 1369

| Father* | Sir Bartholomew de Burghersh2,3 b. c 1304, d. 3 Aug 1355 | |

| Mother* | Elizabeth de Verdun2 b. c 1306, d. 1 May 1360 | |

Sir Bartholomew de Burghersh K.G.|b. s 1323\nd. 5 Apr 1369|p89.htm#i2648|Sir Bartholomew de Burghersh|b. c 1304\nd. 3 Aug 1355|p89.htm#i2652|Elizabeth de Verdun|b. c 1306\nd. 1 May 1360|p89.htm#i2651|Sir Robert Burghersh|d. bt 2 Jul 1306 - 8 Oct 1306|p89.htm#i2653|Maud de Badlesmere|d. a 2 Jan 1306|p89.htm#i2654|Sir Theobald de Verdun|b. 8 Sep 1278\nd. 27 Jul 1316|p89.htm#i2656|Maud de Mortimer|b. c 1286\nd. 17 Sep 1312|p89.htm#i2657| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | say 1323 | 4 |

| Marriage* | 11 May 1335 | Bride=Cicely de Weyland5,6,7,4 |

| Marriage* | before August 1366 | 2nd=Margaret Gisors6,4 |

| Death* | 5 April 1369 | 8,6,4,9 |

| Burial* | Walsingham Abbey, Norfolk4,9 | |