Ercc of Dalriada1

Ercc of Dalriada1

M, #2941

| Father* | Eochaid Muinremur2 d. 474 | |

Ercc of Dalriada||p99.htm#i2941|Eochaid Muinremur|d. 474|p540.htm#i16185|||||||||||||||| | ||

Family | ||

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Aug 2005 |

Loarn of Dalriada1

Loarn of Dalriada1

M, #2942

| Father* | Ercc of Dalriada1 | |

Loarn of Dalriada||p99.htm#i2942|Ercc of Dalriada||p99.htm#i2941||||Eochaid Muinremur|d. 474|p540.htm#i16185|||||||||| | ||

| Last Edited | 24 Aug 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 170-1.

Beatrice de Say1

F, #2943, d. before 19 April 1197

| Father* | William de Say1,2 | |

Beatrice de Say|d. b 19 Apr 1197|p99.htm#i2943|William de Say||p99.htm#i2944||||William de Say|d. Aug 1144|p454.htm#i13617|Beatrice de Mandeville|d. b 19 Apr 1197|p211.htm#i6317||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | before 25 January 1185 | Principal=Sir Geoffrey FitzPiers1,3,4 |

| Death* | before 19 April 1197 | in childbirth3,4,5 |

| Burial* | Chicksand Priory, later transferred to Shouldham Priory3,5 | |

| Residence* | Kimbolton, Norfolk, England3 |

Family | Sir Geoffrey FitzPiers b. 1165, d. 14 Oct 1213 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 29 May 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 96-27.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 160-3.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 87.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 88.

William de Say1

M, #2944

| Father* | William de Say2 d. Aug 1144 | |

| Mother* | Beatrice de Mandeville2 d. b 19 Apr 1197 | |

William de Say||p99.htm#i2944|William de Say|d. Aug 1144|p454.htm#i13617|Beatrice de Mandeville|d. b 19 Apr 1197|p211.htm#i6317|||||||William de Mandeville|b. c 1062\nd. c 1130|p116.htm#i3479|Margaret de Rye|b. c 1075|p116.htm#i3480| | ||

Family | ||

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 20 Jul 2004 |

Margaret de Huntingdon1

F, #2945, b. after 1144, d. 1201

| Father* | Henry of Huntingdon2,3 b. 1114, d. 12 Jun 1152 | |

| Mother* | Ada de Warenne2,3 b. c 1120, d. 1178 | |

Margaret de Huntingdon|b. a 1144\nd. 1201|p99.htm#i2945|Henry of Huntingdon|b. 1114\nd. 12 Jun 1152|p99.htm#i2949|Ada de Warenne|b. c 1120\nd. 1178|p99.htm#i2948|David I. of Scotland "the Saint"|b. c 1080\nd. 24 May 1153|p99.htm#i2951|Countess Maud of Huntingdon|b. 1072\nd. 1131|p85.htm#i2544|Sir William de Warenne|b. 1071\nd. 11 May 1138|p101.htm#i3006|Isabel de Vermandois|b. 1081\nd. 13 Feb 1131|p64.htm#i1915| | ||

| Birth* | after 1144 | 3 |

| Marriage* | 1160 | Groom=Duke Conan IV Brittany1,3 |

| Marriage* | after 1171 | Groom=Humphrey IV de Bohun1,3,4 |

| Death* | 1201 | 3,5 |

| Burial* | Sawtrey Abbey3 | |

| Name Variation | Margaret Bretagne3 |

Family 1 | Duke Conan IV Brittany b. 1138, d. 20 Feb 1171 | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | Humphrey IV de Bohun b. c 1144, d. 1182 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 19 Jul 2005 |

Citations

Humphrey IV de Bohun1

M, #2946, b. circa 1144, d. 1182

| Father* | Humphrey III Bohun4 d. 6 Apr 1187 | |

| Mother* | Margaret of Hereford2,3 b. c 1122, d. 8 Apr 1187 | |

Humphrey IV de Bohun|b. c 1144\nd. 1182|p99.htm#i2946|Humphrey III Bohun|d. 6 Apr 1187|p366.htm#i10962|Margaret of Hereford|b. c 1122\nd. 8 Apr 1187|p211.htm#i6315|Humphrey I. de Bohun|d. c 1129|p458.htm#i13724|Matilda of Salisbury|b. c 1088\nd. 1142|p211.htm#i6316|Miles FitzWalter|b. c 1097\nd. 24 Dec 1143|p90.htm#i2698|Sibyl de Neufmarché|b. c 1090\nd. a 1143|p90.htm#i2697| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1144 | 2 |

| Marriage* | after 1171 | 2nd=Margaret de Huntingdon1,2,5 |

| Death* | 1182 | 1,2 |

| Note | He was constable of England and drove the Scots from Yorkshire during a rebellion against Henry II6 | |

| DNB* | Bohun, Humphrey (IV) de, second earl of Hereford and seventh earl of Essex (d. 1275), magnate, was the eldest son of Henry de Bohun, first earl of Hereford, and Matilda or Maud, daughter of Geoffrey fitz Peter, earl of Essex, and sister and heir of William de Mandeville, earl of Essex. His father (the first Bohun earl of Hereford) died in June 1220, and in June the following year, at the petition of King Alexander of Scotland and the barons of England, Humphrey was permitted to succeed to the family estates, concentrated for the most part in the Welsh marches and in Wiltshire, including the castle of Caldicot in Monmouthshire and a share of the honour of Trowbridge. Through the marriage of Humphrey's grandfather to Margaret, sister of King William of Scotland, the Bohuns also controlled a considerable estate in Scotland. In February 1225 Humphrey de Bohun witnessed the reissue of Magna Carta as earl of Hereford, and his title to the third penny of the county of Hereford was confirmed in October 1225, presumably at the same time that he was belted as earl. William de Mandeville died in 1227, leaving Bohun's mother as countess of Essex for the remainder of her life. Following her death in August 1236 Bohun succeeded to her title, and to the honour and castle of Pleshey in Essex. Earl Humphrey married twice. His first wife was Matilda, daughter of Raoul de Lusignan, count of Eu (d. 1219), whom he had married by 1238 and who brought her husband various lands in Kent. She died on 14 August 1241 and was buried at Llanthony. He married second Matilda of Avebury, who died on 8 October 1273 at Sorges in the Dordogne. In 1227 Bohun joined the earls of Cornwall, Chester, and Pembroke in their brief confederation against the king, but he served on the king's expedition to Brittany in 1230, and, at the coronation of Queen Eleanor in 1236, carried out the ceremonial duties of marshal of the king's household. In 1237 he made a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, and in 1239 he was one of the sponsors at the baptism of Edward, the king's first-born son. From 1239 until 1241 he was sheriff of Kent and constable of Dover. He took part in the king's expedition to Poitou in 1242, and in 1244 assisted the repression of a Welsh rising on the marches. However, later that same year the Welsh rose again, angered, it was said, by Bohun's retention of the dower lands of Isabella de Briouze, his son's sister-in-law and the wife of Dafydd, son of the Welsh prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (d. 1240). In 1246 Bohun was among the English barons who wrote to the pope in defence of the liberties of the church in England. In 1250 he took vows as a crusader, but seems not to have gone on crusade. Two years later he was one of the barons who spoke in defence of Simon de Montfort against the king. In 1253 he joined the king's expedition to Gascony, but took offence at the actions of the king's Lusignan half-brothers who had inflicted summary punishment upon various Welsh mercenaries, without referring the case to the court over which Bohun presided as hereditary constable of the king's army. As a result he returned to England together with various other leading barons. In 1257 he was one of those set to defend the marches against attacks from the Welsh. Humphrey de Bohun joined the confederation of the barons in 1258, and was appointed to enforce the sentence of banishment imposed upon the king's Lusignan kinsmen. Under the provisions of Oxford, he was elected to the baronial council of fifteen and in 1260 was nominated as justice on eyre for the counties of Gloucester, Worcester, and Hereford. Thereafter, however, he broke with the party of Simon de Montfort, and renewed his support for the king, receiving custody of the Welsh lands of the honour of Gloucester between July 1262 and August 1263. He was one of the royalists captured at the battle of Lewes in May 1264, in which his son, Humphrey (V) de Bohun (known as Humphrey the younger), took the side of the barons. Humphrey the younger was himself taken prisoner during the royalist victory at Evesham in 1265, after which Earl Humphrey obtained the reversion of his son's lands. In October 1265 he served as royalist keeper of the city of London, and in 1266 was one of the arbiters appointed to administer the dictum of Kenilworth. He died on 24 September 1275 and was buried at Llanthony (Prima) Priory, in Monmouthshire. Shortly before his death Bohun had conveyed the honour of Pleshey to his younger son, Henry de Bohun. The remainder of his estate passed to his grandson, Humphrey (VI) de Bohun (d. 1298), son and heir of Humphrey the younger, who had died in captivity on 27 October 1265, at Beeston Castle, near Chester. Besides his son Humphrey, Bohun had other sons named Henry, John, and Savaric, and at least four daughters, including Matilda, the wife of Anselm Marshal, earl of Pembroke (d. 1245). He was a regular though not lavish patron of the religious orders, granting and confirming lands to Llanthony, to the Mandeville abbey of Walden in Essex, and shortly before his death to the nuns of Lacock in Wiltshire. Despite his supposed hostility to the king's alien courtiers, it is intriguing to note the Poitevin and Gascon connections of both of his wives. Nicholas Vincent Sources chancery rolls · GEC, Peerage · Paris, Chron. · Ann. mon. · Dugdale, Monasticon, new edn, 6.135 · K. H. Rogers, ed., Lacock Abbey charters, Wilts RS, 34 (1979) · obituary notice, Llanthony Priory Archives PRO, chancery rolls © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Nicholas Vincent, ‘Bohun, Humphrey (IV) de, second earl of Hereford and seventh earl of Essex (d. 1275)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/2775, accessed 23 Sept 2005] Humphrey (IV) de Bohun (d. 1275): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27757 | |

| HTML* | History of the Bown Surname | |

| HTML | Les Seigneurs de Bohon 8 |

Family | Margaret de Huntingdon b. a 1144, d. 1201 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 96-26.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 33.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 193-5.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 18-1.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 34.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S324] Les Seigneurs de Bohon, online http://www.rand.org/about/contacts/personal/Genea/…

Duke Conan IV Brittany1

M, #2947, b. 1138, d. 20 February 1171

| Father* | Alan II (?)2 b. c 1116, d. 15 Sep 1146 | |

| Mother* | Bertha of Brittany (?)2 d. c 1163 | |

Duke Conan IV Brittany|b. 1138\nd. 20 Feb 1171|p99.htm#i2947|Alan II (?)|b. c 1116\nd. 15 Sep 1146|p146.htm#i4379|Bertha of Brittany (?)|d. c 1163|p228.htm#i6829|Count Stephen I. of Brittany|d. 21 Apr 1135|p136.htm#i4059|Hawise d. Guincamp|d. a 1135|p136.htm#i4060|Conan I. of Brittany|b. 1089\nd. 17 Sep 1148|p228.htm#i6828|Maud o. E. (?)||p228.htm#i6826| | ||

| Birth* | 1138 | Brittany2 |

| Marriage* | 1160 | 1st=Margaret de Huntingdon1,2 |

| Death* | 20 February 1171 | 1,2 |

Family | Margaret de Huntingdon b. a 1144, d. 1201 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Ada de Warenne1

F, #2948, b. circa 1120, d. 1178

| Father* | Sir William de Warenne2 b. 1071, d. 11 May 1138 | |

| Mother* | Isabel de Vermandois2 b. 1081, d. 13 Feb 1131 | |

Ada de Warenne|b. c 1120\nd. 1178|p99.htm#i2948|Sir William de Warenne|b. 1071\nd. 11 May 1138|p101.htm#i3006|Isabel de Vermandois|b. 1081\nd. 13 Feb 1131|p64.htm#i1915|William de Warenne|d. 24 Jun 1088|p101.htm#i3007|Gundred (?)|b. c 1051\nd. 27 May 1085|p101.htm#i3008|Hugh Magnus of France|b. 1057\nd. 18 Oct 1101|p64.htm#i1916|Adelaide de Vermandois|b. c 1062\nd. 28 Sep 1124|p64.htm#i1917| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1120 | Surrey, England2 |

| Marriage* | 1139 | Principal=Henry of Huntingdon1,3,2 |

| Death* | 1178 | 3,2 |

| DNB* | Ada [née Ada de Warenne], countess of Northumberland (c.1123-1178), consort of Prince Henry of Scotland, was one of the family of three sons and two daughters of William (II) de Warenne, earl of Surrey (d. 1138), and his wife, Isabel (Elizabeth) de Vermandois (d. 1147), widow of Robert de Beaumont, count of Meulan and earl of Leicester (d. 1118), daughter of Hugues le Grand, count of Vermandois, and granddaughter of Henri I of France. Her eldest brother, William (III) de Warenne, had succeeded as earl of Surrey by 1138 and her sister Gundreda married as her first husband Roger, earl of Warwick (d. 1153). Ada's wider family included the eight children of her mother's first marriage, most notably the mighty Beaumont twins, her half-brothers Robert, earl of Leicester, and Waleran, count of Meulan and earl of Worcester. Her marriage to Prince Henry (c.1115-1152), the only surviving son of David I, king of Scots, was celebrated in England soon after the second treaty of Durham of 9 April 1139, when King Stephen had sought peace with the Scots by confirming Henry's rights to the earldom of Huntingdon, and in addition granting him the earldom of Northumberland. Although Orderic Vitalis speaks of a love match, the marriage was almost certainly arranged at Stephen's command; and possibly one of the Durham treaty's terms (its text is lost) had specifically provided for it in order to bind Henry more effectively to Stephen's cause, in the support of which the Beaumont twins were then at the forefront. While Ada's marriage failed to settle relations between the kingdoms, her contribution to Scottish history was profound. Her public role as first lady of the Scottish court (there was no queen of Scotland from 1131 to 1186) was originally limited by her numerous pregnancies; but her fecundity averted a catastrophe when Henry, the expected successor to the kingship, died prematurely in 1152. During her widowhood she enjoyed in full measure the respect and status to which she was entitled as mother of two successive Scots kings, Malcolm IV and William the Lion. After Malcolm's enthronement as a boy of twelve in 1153, she figured prominently in his counsels and was keenly aware of her responsibilities. According to the well-informed William of Newburgh, Malcolm's celibacy dismayed her, and she endeavoured, albeit fruitlessly, to sharpen his dynastic instincts by placing a beautiful maiden in his bed. She was less frequently at William the Lion's court from 1165, no doubt because of the periodic illnesses that obliged her to turn to St Cuthbert for a cure. Her chief dower estates were the burghs and shires of Haddington and Crail, and Haddington possibly became her main residence. She also had lands in Tynedale at Whitfield, near Hexham, and in the honour of Huntingdon at Harringworth and Kempston. Ada's cosmopolitan tastes and connections reinforced the identification of Scottish élite society with European values and norms. Reginald of Durham regarded her piety as exemplary, and she played a notable role in the expansion of the reformed continental religious orders in Scotland. If she had a preference, it was for female monasticism, and by 1159 she had founded a priory for Cistercian nuns at Haddington, apparently at the instigation of Abbot Waldef of Melrose (d. 1159). Her household attracted Anglo-Norman adventurers, and she personally settled in Scotland knights from Northumberland and from the great Warenne honours in England and Normandy. Ela, the wife of Duncan (II), earl of Fife (d. 1204), was probably one of Ada's Warenne nieces, and her great-nephew Roger (d. 1202) became chancellor of Scotland and bishop of St Andrews. Two of Ada's three sons became kings of Scots; David, the youngest, was the fifth Scottish earl of Huntingdon. She and Henry also had three daughters: Ada (c.1142–1205), who married Florence (III), count of Holland; Margaret (c.1145–1201), who married first Conan (IV), duke of Brittany (c.1135-1171), and second Humphrey (III) de Bohun of Trowbridge (d. 1181); and Maud, or Matilda, who died in infancy in 1152. Ada outlived Henry by twenty-six years and died in 1178. Keith Stringer Sources V. Chandler, ‘Ada de Warenne, queen mother of Scotland (c.1123–1178)’, SHR, 60 (1981), 119–39 · A. O. Anderson, ed., Scottish annals from English chroniclers, AD 500 to 1286 (1908); repr. (1991) · Reginaldi monachi Dunelmensis libellus de admirandis beati Cuthberti virtutibus, ed. [J. Raine], SurtS, 1 (1835) · Jocelin of Furness, ‘Vita sancti Waldeni’, Acta sanctorum: Augustus, 1 (Antwerp, 1733), 241–77 · K. J. Stringer, Earl David of Huntingdon, 1152–1219: a study in Anglo-Scottish history (1985) · D. Crouch, The Beaumont twins: the roots and branches of power in the twelfth century, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought, 4th ser., 1 (1986) · A. O. Anderson and M. O. Anderson, eds., The chronicle of Melrose (1936) © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Keith Stringer, ‘Ada , countess of Northumberland (c.1123-1178)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/50012, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Ada (c.1123-1178): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/500124 |

Family | Henry of Huntingdon b. 1114, d. 12 Jun 1152 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 96-25.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 170-23.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 170-24.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 93-25.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 100-26.

Henry of Huntingdon1

M, #2949, b. 1114, d. 12 June 1152

| Father* | David I of Scotland "the Saint"2,3 b. c 1080, d. 24 May 1153 | |

| Mother* | Countess Maud of Huntingdon2,3 b. 1072, d. 1131 | |

Henry of Huntingdon|b. 1114\nd. 12 Jun 1152|p99.htm#i2949|David I of Scotland "the Saint"|b. c 1080\nd. 24 May 1153|p99.htm#i2951|Countess Maud of Huntingdon|b. 1072\nd. 1131|p85.htm#i2544|Malcolm I. Canmore|b. 1031\nd. 13 Nov 1093|p55.htm#i1631|Saint Margaret of Scotland|b. 1045\nd. 16 Nov 1093|p55.htm#i1630|Waltheof I. of Northumberland|b. 1045\nd. 31 May 1076|p85.htm#i2546|Judith of Lens|b. 1054\nd. a 1086|p85.htm#i2545| | ||

| Birth* | 1114 | 4,5 |

| Marriage* | 1139 | Principal=Ada de Warenne1,4,3 |

| Death* | 12 June 1152 | Kelso, Roxburgh, Scotland4,3,5 |

| Burial* | Kelso, Roxburgh, Scotland3 | |

| DNB* | Henry, earl of Northumberland (c.1115-1152), prince, was the only surviving adult son of David I (c.1085-1153), king of Scots, and his queen, Maud (or Matilda) (d. 1131) [see under David I], widow of Simon (I) de Senlis. From c.1128 his name was linked with his father's in governance, and in 1144 he appears as rex designatus (‘king-designate’) . Although the exact significance of this style is unclear, it seems certain that he had formally been proclaimed as future king; and in practice from the 1130s ‘David's was a dual reign … with joint or at least coadjutorial royal government’ (Barrow, ‘Charters’, 34). This partnership—though Henry was self-evidently the junior partner—had momentous consequences for the Scots monarchy's power and prestige. Henry shared fully in David's policies of modernization by which Scotland began to be transformed into a European-style kingdom, and above all he was inseparably associated with his father in furthering historic Scottish claims to ‘northern England’. Leading vast armies against King Stephen, they made extensive gains at his expense. By the first treaty of Durham (February 1136) Henry was given Doncaster and the lordship of Carlisle, together with his mother's inheritance, the honour and earldom of Huntingdon, which had previously been held by David. However, he never seems to have styled himself earl of Huntingdon. Having done homage to Stephen at York, Henry took the place of honour at the king's right hand during the Easter court of 1136, whereupon Earl Ranulf (II) of Chester (who wanted Carlisle for himself) and possibly Henry's step-brother Simon (II) de Senlis (who nursed rival claims to the Huntingdon honour) withdrew from court in disgust. In January 1138, after Henry had vainly demanded from Stephen the earldom of Northumberland, Scottish assaults were renewed, and at the battle of the Standard (22 August 1138), despite the Scots' defeat, his bravery in leading a cavalry charge against the flank of the Yorkshire army was widely admired. By the second treaty of Durham (9 April 1139) Stephen confirmed or restored Henry's gains of 1136 and gave him Northumberland, albeit under strict safeguards to protect English sovereignty. Almost immediately Henry married Ada de Warenne (c.1123-1178), no doubt at Stephen's request, and then fought throughout the summer in his service. While besieging Ludlow Castle, Stephen rescued Henry from capture after he had been unhorsed, and in 1140 the king supplied an escort to thwart the earl of Chester's plans to entrap Henry on his way to Scotland. But the Scots deserted Stephen for good in the summer of 1141, when Henry's midland honour and earldom passed permanently to Simon (II) de Senlis. Thereafter Henry gave indispensable support to David in annexing the ‘English’ north to the Ribble and the Tees, or at least the Tyne, and ruling it in peace as an integral part of a greater Scoto-Northumbrian realm. He issued coins in his own name at Bamburgh, Carlisle, and Corbridge, and showed his sensitivity to local interests by endowing numerous religious houses. At Carlisle on 22 May 1149 he stood sponsor to Henry Plantagenet for his knighting, and offered to marry one of his own daughters to Chester's son in order finally to settle their differences. His last major act was to join with David in 1150 in founding a Cistercian house at Holmcultram, Cumberland, for monks from Melrose Abbey. Northern English chroniclers acclaimed his kingly qualities and it was said that both English and Scots mourned his passing. Henry's untimely death at the age of about thirty-seven—on which the earldom of Northumberland was assigned to the second of his three sons, the future King William I (the Lion)—was a major blow for Scotland. When David died a year later, in 1153, his successor was not a mature, experienced heir, but a twelve-year-old boy-king, William's elder brother, Malcolm IV; and in 1157 the Scots meekly withdrew to the Tweed–Solway line. Nevertheless, Scotland itself was a stronger kingdom, not least because vigorous exploitation of Cumberland silver had regenerated the Scottish economy, and any assessment of its emergence as a well-founded medieval state must recognize the key importance of Henry's legacy. Perhaps never robust in health, he almost succumbed to a serious illness in 1140, when his recovery was attributed to the miraculous intervention of a revered visitor to the Scottish court, the great Irish reformer St Malachy. Henry died on 12 June 1152, probably at Peebles, and was buried in Kelso Abbey. His youngest son David was born in this same year. Keith Stringer Sources A. O. Anderson, ed., Scottish annals from English chroniclers, AD 500 to 1286 (1908); repr. (1991) · A. O. Anderson, ed. and trans., Early sources of Scottish history, AD 500 to 1286, 2 (1922); repr. with corrections (1990) · G. W. S. Barrow, ed., The charters of King David I: the written acts of David I king of Scots, 1124–53, and of his son Henry earl of Northumberland, 1139–52 (1999) · G. W. S. Barrow, ed., Regesta regum Scottorum, 1 (1960) · G. W. S. Barrow, ‘The charters of David I’, Anglo-Norman Studies, 14 (1991), 25–37 · K. J. Stringer, ‘State-building in twelfth-century Britain: David I, king of Scots, and northern England’, Government, religion and society in northern England, 1000–1700, ed. J. C. Appleby and P. Dalton (1997), 40–62 · G. W. S. Barrow, ‘The Scots and the north of England’, The anarchy of King Stephen's reign, ed. E. King (1994), 231–53 · G. W. S. Barrow, ‘King David I, Earl Henry and Cumbria’, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, [new ser.,] 99 (1999), 117–27 · I. Blanchard, ‘Lothian and beyond: the economy of the “English empire” of David I’, Progress and problems in medieval England: essays in honour of Edward Miller, ed. R. Britnell and J. Hatcher (1996), 23–45 · H. Summerson, Medieval Carlisle: the city and the borders from the late eleventh to the mid-sixteenth century, 1, Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, extra ser., 25 (1993) Likenesses coins, AM Oxf. · coins, BM · coins, National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, Edinburgh · coins, NMG Wales · coins, Stavanger Museum, Norway · seals, U. Durham L., archives and special collections; repro. in Barrow, ed., The charters of King David I, pls. 16, 19–20 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Keith Stringer, ‘Henry, earl of Northumberland (c.1115-1152)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12956, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Henry (c.1115-1152): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/129566 | |

| Event-Misc | 1136 | David resigned his earlship to his son Henry, who did homage to King Stephen, although David had supported Empress Maud, Principal=David I of Scotland "the Saint"5 |

| (Scots) Battle-Standard | 22 August 1138 | Northallerton, Yorkshire, England, Principal=David I of Scotland "the Saint", Principal=Stephen of Blois7,5,8 |

| Title* | 1139 | Earl of Huntingdon and Northumberland, after peace was made with the English5 |

| Note* | He was a favorite of King Stephen and remained with him in England for some time.5 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1150 | He founded the Abbey of Holmcultram in Cumberland5 |

Family | Ada de Warenne b. c 1120, d. 1178 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 96-25.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 170-22.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 170-23.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 114.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 21.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 256.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 170-24.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 93-25.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 115.

William King of Scots "the Lion"1

William King of Scots "the Lion"1

M, #2950, b. 1143, d. 4 December 1214

| Father* | Henry of Huntingdon1,2 b. 1114, d. 12 Jun 1152 | |

| Mother* | Ada de Warenne1,2 b. c 1120, d. 1178 | |

William King of Scots "the Lion"|b. 1143\nd. 4 Dec 1214|p99.htm#i2950|Henry of Huntingdon|b. 1114\nd. 12 Jun 1152|p99.htm#i2949|Ada de Warenne|b. c 1120\nd. 1178|p99.htm#i2948|David I. of Scotland "the Saint"|b. c 1080\nd. 24 May 1153|p99.htm#i2951|Countess Maud of Huntingdon|b. 1072\nd. 1131|p85.htm#i2544|Sir William de Warenne|b. 1071\nd. 11 May 1138|p101.htm#i3006|Isabel de Vermandois|b. 1081\nd. 13 Feb 1131|p64.htm#i1915| | ||

| Birth* | 1143 | 1,2 |

| Marriage* | 5 September 1166 | Woodstock, England2 |

| Marriage* | Woodstock, Principal=Ermengarde de Beaumont3,4 | |

| Death* | 4 December 1214 | Stirling, Scotland1,2 |

| Burial* | Aberbrothock, Scotland2 | |

| (Witness) Biography | In 20 Hen II, Bernard de Balliol and Robert de Stuteville relieved Alwick Castle. During the march to Alnwick, a dense fog appeared. Balliol reportedly said, "Let those stay that will, I am resolved to go forward, although none follow me, rather than dishonour myself by tarryng here." He seized the King of the Scots with his own hand and sent him to Richmond Castle as prisoner., Principal=Bernard de Baliol, Principal=Robert de Stuteville5 | |

| (Witness) Event-Misc | 1174 | Uchtred and Gilbert accompanied King William the Lion on a march into England, where William was captured, following which the brothers tried to regain their independence. They expelled the king's officers and appealed to King Henry for recognition, but fell to quarreling amongst themselves and thus ended the effort., Principal=Uchtred of Galloway, Principal=Gilbert of Galloway6 |

| Event-Misc* | 1206 | York, William Longespée escorted King William the Lion to meet King John, Principal=Sir William Longespée7 |

Family 1 | ||

| Child | ||

Family 2 | ||

| Child |

| |

Family 3 | Ermengarde de Beaumont d. 11 Feb 1233 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 5 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 170-24.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 3.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 115.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 21.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 102.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Longespée 3.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

David I of Scotland "the Saint"1

David I of Scotland "the Saint"1

M, #2951, b. circa 1080, d. 24 May 1153

| Father* | Malcolm III Canmore1,2 b. 1031, d. 13 Nov 1093 | |

| Mother* | Saint Margaret of Scotland1,2 b. 1045, d. 16 Nov 1093 | |

David I of Scotland "the Saint"|b. c 1080\nd. 24 May 1153|p99.htm#i2951|Malcolm III Canmore|b. 1031\nd. 13 Nov 1093|p55.htm#i1631|Saint Margaret of Scotland|b. 1045\nd. 16 Nov 1093|p55.htm#i1630|Duncan I. MacCrinan|b. c 1001\nd. 14 Aug 1040|p98.htm#i2915|Sibel (?)|b. c 1009|p114.htm#i3404|Edward the Ætheling|b. 1016\nd. 1057|p55.htm#i1632|Agatha of Hungary|b. bt 1023 - 1030\nd. c 1068|p55.htm#i1633| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1080 | 1,3 |

| Marriage* | 1113 | 2nd=Countess Maud of Huntingdon1,2,3 |

| Death* | 24 May 1153 | Carlisle, Cumberland, England1,2 |

| Burial* | Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland2,4 | |

| Title* | Earl of Huntingdon by right of his wife, King of Scotland5 | |

| DNB* | David I (c.1085-1153), king of Scots, was the sixth and youngest son of Malcolm III (d. 1093) and his second wife, Margaret (d. 1093). The royal brother, c.1085–1124 Despite the violent reaction which followed Malcolm III's death in 1093, when the succession of his eldest son, Duncan II, was opposed by the conservative Scottish nobles who wished to make Malcolm's brother, Donald III, king in accordance with older custom, there was strong support, perhaps mainly in southern Scotland, for the novel practice of linear father-to-son succession. The direct heirs of Malcolm III were supported by William the Conqueror's sons William Rufus and Henry I. Although one of David's elder brothers, Edmund, allied himself to their uncle Donald, the other brothers, Edgar and Alexander I, along with David himself, fled for safety to England. While Edgar, with Rufus's backing, strove to make himself king of Scots (successfully from 1097), David was attached to the household of the future Henry I and may have been granted a small estate in western Normandy where Henry had lands and a sizeable following of lords and knights. It must have been known that Edgar would have no children, but his heir was the next brother, Alexander, married to a bastard daughter of Henry I. David's prospects might have lain in England or on the continent, although his descent would entitle him to some share of royal lordships after Alexander I's accession in 1107. From 1100 his elder sister Edith, her name altered to Maud, had been the wife of Henry I. His association with the English court doubtless gave added force to the appeal which David was later said to have had to make to the baronage of northern England, for assistance in compelling Alexander I to hand over the appanage in Scottish Cumbria and eastern Scotland south of Lammermuir which had apparently been bequeathed to David by King Edgar. Precisely when this transfer of regional authority was made is not known, but it may have been a little before David's conspicuous promotion south of the border. At the end of 1113 David, who had hitherto enjoyed only the style of ‘the queen's brother’, was given by King Henry the prize of a rich, highly born heiress, Maud de Senlis. Maud [Matilda] (d. 1131) was the daughter of Waltheof, earl of Northumbria (d. 1076), son of Earl Siward who had helped to put Malcolm III on the Scottish throne, and Judith (d. in or after 1086), a niece of William the Conqueror. Maud's first husband was Simon (I) de Senlis (or St Liz; d. 1111×13) , a knight who had served the Conqueror and Rufus, under whom he gained the rank of earl. With Simon, Maud had two sons, and she would have been nearly forty when she married David of Scotland, her junior by almost ten years. The lands acquired by David on his marriage, stretching from south Yorkshire to Middlesex but chiefly concentrated in the shires of Northampton, Huntingdon, Cambridge, and Bedford, formed what came to be known as the ‘honour of Huntingdon’. Its possession made David an important figure in Anglo-Norman court circles. As late as 1130, after he had become king, he is recorded as presiding over the treason trial of Henry I's chamberlain, Geoffrey Clinton. Acquisition of this great lordship was marked by King Henry's grant of an earldom, but to assign the names Huntingdon or Northampton to this estate before the mid-twelfth century is anachronistic. When in Stephen's reign the Senlis family and the Scottish royal house vied for control of the honour, which was never partitioned, the former preferred the title earl of Northampton (given by Stephen), while the Scots simply spoke of the honour of Huntingdon without using any territorial style. In southern Scotland, David quickly showed what was to prove the overriding passion of his life, reform of ecclesiastical institutions and revival of religion. Between 1110 and 1118 he restored the ancient see of Glasgow, of which he made his chaplain John bishop, consecrated by Pope Paschal II (r. 1099–1118) at David's request. In the early 1120s an inquest was held to ascertain the ancient landed endowments of the see, many of which had been sequestrated. Fresh endowments were provided and a new cathedral was begun, dedicated in 1136. David brought to Selkirk a community of monks from Tiron, north of Chartres. In 1128 the convent migrated to Kelso, beside the flourishing centre of Roxburgh, where their abbey grew into the richest in Scotland. The Tironensians, outstandingly successful in Scotland, were the earliest of the congregations of reformed Benedictines (which were the dominant feature of monastic life in north-west Europe in this period) to establish themselves north of the channel. David I and the Scottish nobility David's sister Queen Maud died in 1118, by which date it may have seemed probable that their brother Alexander I would die childless. Soon after Alexander's death on 23 April 1124, David was inaugurated king of Scots at Scone. It is reported by Ailred of Rievaulx (d. 1167) that the attendant bishops had difficulty persuading the new king to undergo the essentially pagan ceremony of inauguration, at which the earl of Fife, as head of a junior segment of the royal lineage, placed the king on the famous stone of Scone (or stone of destiny), while the royal bard bestowed the rod or wand of kingship. David I's achievements as king are most easily understood if the secular and ecclesiastical spheres are treated separately. It must, however, be emphasized that the division is modern and artificial. There is no evidence, and it seems improbable, that David himself drew any sharp distinction between his roles as guardian of the realm and protector of holy church. Given the king's upbringing and marriage and his lengthy experience of the Anglo-Norman court it was inevitable that he perceived lordship in feudal terms. Probably already while ruler of southern Scotland, during his brother's reign, he established followers from Normandy and England, such as Robert (I) de Brus (d. 1142), Hugh de Morville and Ranulf de Soulles, as lords of substantial portions of the princely demesne of Cumbria. Such men were trained in cavalry warfare and the use of motte-and-bailey castles. By the 1140s the greater part of southern Scotland, with the exception of Galloway and Nithsdale, had been allotted to incoming followers of the king. In the west they were given extensive lordships (for example, Annandale, Kyle Stewart), while in the east smaller, discrete, estates were the norm for newly created fiefs. Many (probably all) of these fiefs were held for military service, including the duty of garrisoning the king's castles. Although David I was willing to repeat this pattern of fief-creation in Scotia, north of the Forth–Clyde line, the outstanding fact of his reign in secular affairs was the continued and peaceful coexistence of a newly established military feudalism with the older arrangement of provinces ruled by hereditary dynasties of mormaers (literally ‘great officers’, ‘chief stewards’). These were territorial in character, probably a legacy of the pre-ninth century Pictish kingdom. An exception to the rule of peaceful coexistence was the revolt in 1130 by Angus, mormaer of Moray. Angus was the son of a daughter of Lulach Mac Gillachomgan, who had been briefly king of Scots in 1057–8. Taking advantage of the king's absence in the south of England, Angus led an army south by the east coast route. Just south of the crossing of the River North Esk near Stracathro, the men of Moray were met by a force under the command of King David's constable Edward and suffered a decisive defeat, Angus himself being killed. Had the battle gone the other way, the course of Scottish history might well have been significantly different. As it was, David annexed the province of Moray to the crown and established followers of continental origin, notably Flemings, in estates which had presumably belonged to the mormaers. In all the provincial earldoms or mormaerdoms the king possessed rights, for example, military service, justice, and certain types of revenue, while in some, especially Fife, Gowrie, and Angus, as well as in Moray after 1130, he had extensive lands in demesne. These were exploited to create and support the castles and trading towns (‘burghs’) which in David I's time were established at Perth, Forfar, Montrose, Aberdeen, Elgin, Forres, and Inverness. A mixture of the old and the new, in which the crown held the initiative, characterized the political entity coming to be known as the kingdom of the Scots in the earlier twelfth century. The transformation of the church However powerfully he had left his mark on Scottish secular government, David I was to be remembered, not without reason, as the king who almost single-handedly transformed the church within his realm, with a generosity which is said to have prompted King James I (r. 1406–37) to observe ruefully that David's grants to the religious had made him ‘a sair sanct to the croun’ (Ritchie, 337). He was personally responsible for founding monasteries of the Tironensian, Cistercian, and Augustinian orders, while he enlarged the Benedictine priory of Dunfermline to form the second richest abbey in Scotland, and established Benedictines of the Cluniac observance on the Isle of May. He was largely responsible for founding an Augustinian cathedral priory at St Andrews, and he welcomed the military orders of the Hospital and the Temple. Such a rich infusion of monastic life, closely tied as it was to forms of regular observance universal throughout western Christendom, would have altered the Scottish church almost beyond recognition. But David went much further, imposing a territorially defined system upon the Scottish bishoprics. This involved strengthening the authority of the two largest dioceses of St Andrews (which he strove unsuccessfully to have recognized as metropolitan) and Glasgow. Almost certainly David created the dioceses of Caithness and Moray, while he re-established the see of the bishop of north-east Scotland at Old Aberdeen, close to the royal castle and burgh of Aberdeen. Within the dioceses, whose boundaries were now relatively well defined, the king encouraged the formation of parish churches with fixed territories, served by priests supported by tithes (Scottish, ‘teinds’), payment of which was enforced by the secular power. Anglo-Scottish relations Scotland's relations with England remained peaceful and even friendly as long as Henry I was alive. Not only was there a close personal tie between the two kings, but it is clear also that Henry's plan to have his daughter, the Empress Matilda (d. 1167), recognized as his heir—even though a woman and married to the count of Anjou—was fully accepted by the king of Scots, who in 1127 was first among the lay magnates to swear an oath of fealty to Matilda as prospective successor to her father. David enjoyed a special position within the English kingdom, being entrusted by Henry with important administrative roles and judicial decisions. The Anglo-Scottish peace was shattered by Stephen of Blois's bid for the crown at the end of 1135, when David took possession of Carlisle and Cumberland, as his father had held them, enforcing a Scottish restoration which he had never attempted as long as Henry I was king of England. The Scots were compelled to recognize Stephen's authority, at least de facto, and by David's first treaty with Stephen (February 1136) he retained Cumbria, relinquished Northumberland, and had his son and heir Henry recognized as lord of the honour of Huntingdon. Relations with Stephen broke down in 1137, however, and by 1138 the Scots were invading Northumberland and pushing even further south, towards Yorkshire, probably with the aim of establishing Scottish authority over the whole of England north of Lancashire and the Tees. But David's strategy received a setback on 22 August 1138, when a well-disciplined force of English barons and knights met a large but unruly Scottish host on Cowton Moor near Northallerton, and in the battle of the Standard inflicted a severe defeat. Stephen's difficulties in southern England prevented him from exploiting this English victory, and by his second treaty with the Scots (Durham, 9 April 1139) he was forced in effect to cede to David control over England between Tees and Tweed, as well as continued enjoyment of the honour of Huntingdon. After Stephen was captured by his enemies in 1141, David and his son joined forces with the empress when she made her unsuccessful bid for the English throne. Even though the rout of the empress's forces at Winchester, on 14 September 1141, sent David and Henry northward again in undignified flight, their discomfiture did not affect their position north of Tees, where they remained in control until David's death. The honour of Huntingdon, however, was now lost. Indeed, at this period the Scottish king even exercised lordship over the honour of Lancaster, while in 1149 he entertained the young Henry of Anjou, son of the empress, at a splendid ceremony at Carlisle, where David conferred knighthood upon the future king of England and extracted a solemn promise, soon to be broken, that after Henry's accession the Scots would be left in undisturbed enjoyment of the English northern counties. Contemporary English writers reproached David for allowing his followers to commit many atrocities during the invasions of 1137–8, but at least one of them, William of Newburgh, gives the Scottish king credit for enforcing a twelve-year peace throughout northern England when it was conspicuously absent in the south. The achievements of David I David I was driven by a clear and consistent vision, pious and authoritarian, of what his kingdom should be: Catholic, in the sense of conforming to the doctrines and observances of the western church; feudal, in the sense that a lord–vassal relationship, involving knight-service, should form the basis of government; and open, in the sense that external (especially continental) influences of all kinds, religious, military, and economic, were encouraged and exploited to strengthen the Scottish kingdom. Alongside his eclecticism, David's strong sense of the autonomy of his realm and of his own position within it must be acknowledged. The surviving numbers of his charters, compared with those of his predecessors, surely point to an increase in the sophistication, and probably also in the activity, of government. During David's reign the administration of royal justice became more firmly established and was organized more effectively. Those who enjoyed their own courts were told that the king would intervene if they failed to provide justice. The addresses of royal charters and writs (Scottish ‘brieves’) show that from c.1140 justiciars were appointed. Although none is known by name, these officers were clearly the predecessors of the named justiciars of succeeding reigns. David prevented his bishops (save only Galloway) recognizing any claims by York or Canterbury to ecclesiastical authority over the Scottish church, and he refused homage to Stephen, only allowing his son to do homage for Northumberland and Huntingdon. He restored the southern border of his kingdom west of the Pennines to Westmorland, where it had run before 1092. He was the first king of Scots to have a coinage struck in his name, in the form of silver sterlings minted at Carlisle, Berwick, Edinburgh, and elsewhere, from c.1139 onwards. His greatest failure, for which he cannot be blamed, lay in the succession. From c.1136, when his son Henry (understandably, in view of Maud's probable age at her second marriage, the only son to survive to adulthood) would have been about twenty, David had begun to associate his heir with himself in royal government. From 1139 onwards, indeed, it is not misleading to speak of joint kingship in Scotland. But Henry died tragically young in 1152. David himself died a year later, on 24 May 1153 at Carlisle Castle; he was buried in early June before the high altar of the church of Dunfermline Abbey. His heir, Henry's eldest son, Malcolm IV, was only twelve and no match for the vigorous Henry of Anjou who succeeded to the English throne at the end of 1154. Yet Malcolm succeeded comparatively peacefully and the greater part of his grandfather's legacy remained to the Scottish kingdom as it was to develop, on foundations which David had largely laid, during the remaining medieval centuries. G. W. S. Barrow Sources G. W. S. Barrow, ed., The charters of King David I: the written acts of David I king of Scots, 1124–53, and of his son Henry earl of Northumberland, 1139–52 (1999) · A. C. Lawrie, ed., Early Scottish charters prior to AD 1153 (1905) · Ailred of Rievaulx, ‘Eulogium Davidis’, Vitae antiquae sanctorum qui habitaverunt in ea parte Britanniae nunc vocata Scotia vel in ejus insulis, ed. J. Pinkerton (1789) · Symeon of Durham, Opera · R. Howlett, ed., Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, 3, Rolls Series, 82 (1886) · G. W. S. Barrow, ed., Regesta regum Scottorum, 1 (1960) · R. L. G. Ritchie, The Normans in Scotland (1954) · G. W. S. Barrow, ‘The charters of David I’, Anglo-Norman Studies, 14 (1991), 25–37 · G. W. S. Barrow, David I of Scotland (1124–53): the balance of new and old (1985) · A. O. Anderson and M. O. Anderson, eds., The chronicle of Melrose (1936) · A Scottish chronicle known as the chronicle of Holyrood, ed. M. O. Anderson (1938) · GEC, Peerage · Johannis de Fordun Chronica gentis Scotorum, ed. W. F. Skene (1871) · Johannis de Fordun Chronica gentis Scotorum / John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish nation, ed. W. F. Skene, trans. F. J. H. Skene, 2 (1872), 224 Archives Durham Cath. CL, charters · NA Scot. | NL Scot., Edinburgh Advocates MSS Likenesses illuminated initial, c.1159, NL Scot., charter of Malcolm IV for Kelso Abbey [see illus.] © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press G. W. S. Barrow, ‘David I (c.1085-1153)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7208, accessed 24 Sept 2005] David I (c.1085-1153): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7208 Maud (d. 1131): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/493536 | |

| Crowned* | 25 April 1124 | King of Scotland1,5 |

| Event-Misc* | 1136 | David resigned his earlship to his son Henry, who did homage to King Stephen, although David had supported Empress Maud, Principal=Henry of Huntingdon5 |

| Battle-Standard* | 22 August 1138 | Northallerton, Yorkshire, England, Principal=Stephen of Blois, Witness=Robert de Stuteville, Witness=Bernard de Balliol, Scots=Henry of Huntingdon, English=Robert de Lacy, English=William de Percy, English=William Peverell, Scots=Eustace FitzJohn7,5,8 |

| (Witness) Knighted | 1149 | Carlisle, England, by his great uncle, David, King of Scotland, Principal=Henry II Curtmantel9 |

Family | Countess Maud of Huntingdon b. 1072, d. 1131 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 170-22.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 113.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 226.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 114.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 21.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 256.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 2.

Eleanor Gifford1

F, #2952, b. 1275, d. before 1325

| Father* | Sir John Gifford b. c 1232, d. 28 May 1299; daughter and coheir2,3 | |

| Mother* | Maud de Clifford2 d. bt 1282 - 1285 | |

Eleanor Gifford|b. 1275\nd. b 1325|p99.htm#i2952|Sir John Gifford|b. c 1232\nd. 28 May 1299|p99.htm#i2955|Maud de Clifford|d. bt 1282 - 1285|p99.htm#i2956|Elias Gifford|b. c 1185\nd. b 2 May 1248|p464.htm#i13893|Alice Maltravers||p493.htm#i14790|Walter de Clifford|d. c 23 Dec 1263|p99.htm#i2958|Margaret verch Llywelyn|d. a 1268|p99.htm#i2959| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | 1275 | 4 |

| Marriage* | before 1307 | Principal=Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere1,5,4 |

| Death* | before 1325 | 1 |

| Event-Misc | 20 December 1307 | Dispensation to Fulk le Strange, lord of Witechirche, and Margaret (als. Eleanor), d. of late Jn. Giffard, lord of Corsham, to continue married and their issue legitimate, though related in 4th degree, Principal=Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere5 |

Family | Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere b. c 1267, d. 23 Jan 1324/25 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 9 Apr 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-30.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-29.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 113.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 123.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 294.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-31.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 295.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 232.

Elizabeth le Strange1

F, #2953

| Father* | Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere1,2 b. c 1267, d. 23 Jan 1324/25 | |

| Mother* | Eleanor Gifford1 b. 1275, d. b 1325 | |

Elizabeth le Strange||p99.htm#i2953|Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere|b. c 1267\nd. 23 Jan 1324/25|p91.htm#i2715|Eleanor Gifford|b. 1275\nd. b 1325|p99.htm#i2952|Sir Robert le Strange|d. b 10 Sep 1276|p99.htm#i2963|Eleanor de Whitchurch|d. c 1304|p99.htm#i2966|Sir John Gifford|b. c 1232\nd. 28 May 1299|p99.htm#i2955|Maud de Clifford|d. bt 1282 - 1285|p99.htm#i2956| | ||

| Marriage* | before March 1323 | Principal=Sir Robert Corbet1 |

| Event-Misc | 15 March 1323 | Dispensation to Robert Corbet, lord of Morton, and Elizabeth, d. of Fulk le Strange of Aquitaine, to remain married and their issue legitimate, though related in 4th degree., Principal=Sir Robert Corbet2 |

| Last Edited | 21 Oct 2004 |

Sir Robert Corbet1

M, #2954, b. 1304, d. 1375

| Birth* | 1304 | 1 |

| Marriage* | before March 1323 | Principal=Elizabeth le Strange1 |

| Death* | 1375 | 1 |

| Event-Misc* | 15 March 1323 | Dispensation to Robert Corbet, lord of Morton, and Elizabeth, d. of Fulk le Strange of Aquitaine, to remain married and their issue legitimate, though related in 4th degree., Principal=Elizabeth le Strange2 |

| Last Edited | 23 Apr 2005 |

Sir John Gifford1

M, #2955, b. circa 1232, d. 28 May 1299

|

| Father* | Elias Gifford b. c 1185, d. b 2 May 1248; son and heir2 | |

| Mother* | Alice Maltravers3 | |

Sir John Gifford|b. c 1232\nd. 28 May 1299|p99.htm#i2955|Elias Gifford|b. c 1185\nd. b 2 May 1248|p464.htm#i13893|Alice Maltravers||p493.htm#i14790|Helias Giffard|b. s 1153|p494.htm#i14791|Joan Maltravers|d. a 1221|p494.htm#i14792|Sir John Maltravers||p523.htm#i15666|||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1232 | On St. Wulstan's Day (19 Jan)1,2,3 |

| Marriage* | circa 1257 | 2nd=Maud de Clifford1,4 |

| Marriage | 1271 | Conflict=Maud de Clifford3 |

| Marriage* | 1286 | On 9 May 1285, Richard, Bishop of Hereford had written to the Pope for dispensation of the marriage within the 3rd and 4th degrees of consanguinity., 2nd=Margaret (?)5 |

| Death* | 28 May 1299 | Boyton, Wiltshire, England2 |

| Death | 29 May 1299 | Boyton, Wiltshire, England1 |

| Burial* | 11 June 1299 | Malmesbury Abbey2,3 |

| DNB* | Giffard, John, first Lord Giffard (1232-1299), baron, was born on 19 January 1232, the son of Elias Giffard (d. 1248), holder of the castle and barony of Brimpsfield, Gloucestershire, and extensive lands in both Gloucestershire and Wiltshire. His mother was Alice, daughter of John Maltravers. His father formally betrothed him at Arrow in Warwickshire at the age of four years to Alberada (Aubrée) de Canville, daughter of Thomas de Canville of Arrow, who was his age. The arrangement did not proceed to marriage, and the girl later entered a nunnery. He was in the queen's wardship until 1253, and is found in 1256 having a respite of knighthood until his return from a journey to Ireland with John de Mucegros. He was active in the campaigns against Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1257–8 and 1260–61. In August 1262 he is found associated with the young aristocratic victims of the Savoyard purge of Edward's household, banned from tourneying or riding around in arms. Like them, he gravitated into the household of Simon de Montfort, earl of Leicester, leader of the opposition to ‘alien’ influences at court. Giffard was active in Montfort's interest through most of the period of the baronial rebellion, being one of those who seized the alien bishop of Hereford, Peter d'Aigueblanche, in June 1263. In August he was given control of St Briavels and the Forest of Dean, and in December consolidated his power in the southern march with the keeping of the counties of Gloucester, Worcester, and Hereford. However, he had not forgotten his former attachment to Edward. In the same month, perhaps annoyed by Montfort's temporizing with Prince Llywelyn, he undertook to support Edward (saving his oath to support the provisions of Oxford). When his friends, the former associates of Edward, returned to the latter's household in October 1263, Giffard at first accepted a £50 money fee from Edward, but returned it after Christmas, and remained with Montfort. He was active in attacking Edward's supporters in the southern march in the winter of 1263, and, according to Robert of Gloucester, he assisted Montfort's capture of the town (but not castle) of Gloucester by secretly penetrating it dressed as a Welsh wool merchant. But when the time came to defend Gloucester against the Lord Edward in February 1264 he was unsuccessful. However, he captured Warwick and its earl for the Montfortians in April. He fought in Earl Simon's household at the battle of Lewes on 14 May 1264, when he was briefly taken prisoner, but himself took prisoner William de la Zouche. It was immediately after the battle that Giffard left Earl Simon's retinue and entered that of Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester and Hertford. The move made political sense for him, as Earl Gilbert was the dominant magnate in the southern march. But it led to ill feeling between Giffard and his former associates, as he took his prisoner, Zouche, with him, and also as he joined in the fighting between Earl Gilbert's brother, Thomas, and the sons of Earl Simon. The tournament at Dunstable arranged to settle the differences in February 1265 was prohibited, and Giffard and Earl Gilbert took this as their excuse to retreat to the southern march. Clare and Giffard concentrated their forces in the Dean area, uniting with the Lord Edward after his escape in late May, and assisting in his capture of the Severn valley. Giffard fought for the royalists at Evesham on 4 August 1265, taking a number of prisoners, and later accumulating great sums of money in ransoms and confiscated lands. He had pardon for his offences while with Montfort, and retained Dean until 1270. In the aftermath of Evesham Giffard used his cash surplus to become a notable baronial player in the loan market. His adherence to Gilbert de Clare also brought him considerable gains, notably a grant in fee of a rent of £20 in the earl's borough of Burford, Oxfordshire, and manor of Badgeworth, Gloucestershire, and control of both places for life. His public career seems to have declined somewhat after Evesham, for reasons that are not immediately clear but which may have been perfectly innocent: a simple preference for rural pursuits, perhaps. The almost obsessional enthusiasm with which he devoted himself to the hunt, both in royal forests and his own parks, has been remarked upon. But he did not confine himself to hunting beasts of the chase. In October 1271 he caused a notorious scandal when he abducted from her house at Canford, Wiltshire, the (allegedly) unwilling Matilda Longespée, daughter and heir of Sir Walter de Clifford of Glasbury and widow of William (III) Longespée, sometime heir to the earldom of Salisbury. It seems that the two had already been negotiating a marriage contract, but Giffard became impatient and attempted a rough wooing. Giffard was heavily fined, but eventually managed to persuade the king to sanction the match. This marriage brought him the Clifford lordships and castles of Bronllys and Glasbury in Brecon, Llandovery in Deheubarth, and other manors in Shropshire for life, and brought him into the ranks of marcher lords. Giffard's military skills and marcher connections remained much valued despite advancing years. He was still pursuing an enthusiasm for the tournament in 1274 (then aged forty-two), when he attended one at Newark with a large following. He played a full part in the campaigns of Edward I against Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, prince of Gwynedd, and was involved in the final campaign in which the prince was killed in December 1282. A year later he was rewarded with the lordship of Is-Cennen in west Wales, and in 1290 had the grant of the castle of Dynefwr (the royal seat of the dynasty of Deheubarth) for life, which greatly enhanced his position as a marcher baron. As such, he (with others) came into conflict with Humphrey (VI) de Bohun, earl of Hereford, in 1290–91. He was involved in dealing with the major Welsh uprising of 1294–5, commanding a force that relieved the castle of Builth in November 1294. King Edward showed his faith in Giffard by employing him as commander of the castle of Podensac, south of Bordeaux in Gascony, in the Anglo-French war of 1294–5. But the castle was surrendered by Giffard to Charles de Valois, which caused outrage among the Gascon nobility, and led to Giffard's trial and further trouble, when his troops mutinied. John Giffard returned to England, and remained in favour, attending councils and parliaments up to the time of his death. He died at his house at Boyton, Wiltshire, on 29 May 1299, and was buried on 11 June at Malmesbury Abbey. His wife Matilda had died in or soon after 1281, and he had married in 1286 Margaret, widow of John de Neville (d. 1282). She died in 1338. Giffard left several children. He had three daughters with his first wife: Katherine, who married Nicholas Audley, Eleanor, and Matilda, still unmarried in 1299, who (with an elder half-sister) shared the Clifford inheritance from their mother. His only son, also John Giffard, was born to his second wife in or about 1287, and remained in wardship until 1308, when he inherited the lordship of Brimpsfield and the rest of his father's acquisitions. The elder John Giffard's career is not without interest. His passionate involvement with the politics of the later Henrician monarchy, and his fitful relationship with the Lord Edward, dominated his young adulthood. His later years, following his final frenzied behaviour over Matilda Longespée, are a marked contrast. He settled into the mould of the Edwardian magnate, his career revolving around public service, the king's military ambitions, and his own financial and estate interests. His foundation of Gloucester Hall at Oxford (1283–4), as a Benedictine house within the university for students from the ancient abbey his family had long patronized, is an interesting manifestation of a new direction in aristocratic patronage, and is directly comparable with the patronage of Merton College by Sir Richard de Harcourt, another middle-ranking Edwardian aristocrat. David Crouch Sources Chancery records · CIPM, vol. 3 · ‘Hailes chronicle’, BL, Cotton MS Cleopatra D.iii · W. H. Hart, ed., Historia et cartularium monasterii Sancti Petri Gloucestriae, 3 vols., Rolls Series, 33 (1863–7) · exchequer, forest proceedings, PRO, E32/188 · Ann. mon., vol. 4 · [W. Rishanger], The chronicle of William de Rishanger, of the barons' wars, ed. J. O. Halliwell, CS, 15 (1840) · J. G. Edwards, ed., Littere Wallie (1940) · GEC, Peerage · J. N. Langston, ‘The Giffards of Brimpsfield’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 65 (1944), 105–28 · J. Birrel, ‘A great thirteenth-century hunter: John Giffard of Brimpsfield’, Medieval Prosopography, 15 (1994) © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press David Crouch, ‘Giffard, John, first Lord Giffard (1232-1299)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10651, accessed 25 Sept 2005] John Giffard (1232-1299): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/106516 | |

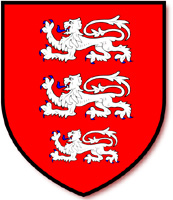

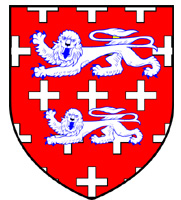

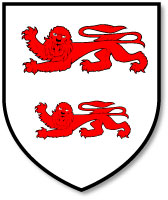

| Arms* | Gules, troiz leons passauntz d'argent (Walford). Gu. 3 lions passant arg. (Charles, St. George, Segar, Camdem, (1, 2 Nob).2 | |

| Name Variation | Sir John Giffard2,3 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1256 | He fought in the Welsh Wars2 |

| Event-Misc | 1263 | He was Governor of St. Briavel's Castle.2 |

| Event-Misc | 11 June 1263 | He and other barons seized the Bishop of Hereford and took him to Eardisley Castle.5 |

| Event-Misc | 18 September 1263 | He was pardoned for failing to keep the Provisions of Oxford5 |

| Event-Misc | 24 December 1263 | He was appointed keeper of the castle of St. Briavel and the forest of Dean5 |

| Event-Misc | April 1264 | He was in command at Kenilworth and destroyed Warwick Castle taking the Earl and Countess prisoners5 |

| (Simon) Battle-Lewes | 14 May 1264 | The Battle of Lewes, Lewes, Sussex, England, when King Henry and Prince Edward were captured by Simon of Montfort, Earl of Leicester. Simon ruled England in Henry's name until his defeat at Evesham, Principal=Henry III Plantagenet King of England, Principal=Simon VI de Montfort7,8,9,10,11,12 |

| Event-Misc | 16 February 1264/65 | He was prohibited from participating in the tournament at Dunstaple, and was ordered to attend Council three days later.5 |

| (Edward) Battle-Evesham | 4 August 1265 | Evesham, Principal=Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England, Principal=Simon VI de Montfort13,14,15 |

| Event-Misc | August 1265 | He was pardoned for his previous tresspasses after fighting for the King at the Battle of Evesham5 |

| Event-Misc* | 10 March 1271 | Commission re complaint by Maud Longespe, King's Baroness, that Jn. Giffard abducted her at Kaneford Manor, took her against her will to his castle at Brinsmead and detained her there. John says that she consented, and has made fine in 300 m. for her marriage, already contracted. She is infirm and cannot come., Principal=Maud de Clifford2 |

| Event-Misc | 5 October 1273 | Prince Edmund, sine lic. has alienated Dyluin Manor to Jn. G.2 |

| Event-Misc | 24 April 1274 | He was a commissioner empowered to make a truce between Llywelyn ap Gruffud and Humphrey de Bohun5 |

| Summoned* | 1 July 1277 | serve against the Welsh. He acknowledges 1 Kt. Fee in Sherinton for his Barony, and 2 Fees in Aldinton for his wife2 |

| Event-Misc | 27 April 1279 | Archbishop Walter Giffard, dec., held Boyton Maonor, Wilts., of John Giffard, and left bro. h. Godfrey, Bishop or Worcester.2 |

| Event-Misc | 26 February 1280 | Grant to him for life the run of all the King's forests in Salop, so far as deer, started in his chace of Corffham, shall run in the day2 |

| Event-Misc | 8 October 1281 | John and Matilda nominate attorneys in Ireland, Principal=Maud de Clifford2 |

| Event-Misc | 6 November 1281 | Lic. to hunt wolves with his own hounds in all the King's forests of England but not to take the King's great deer, though if his greyhounds escape the leash and take any he shall not be molested. King's forester shall advise and assist him in the capture of wolves, and he may use nets or any other suitable means2 |

| Summoned | 1282 | serve against the Welsh, acknowledges 2 Kt. Fees, to be served by himself and 1 Kt.2 |

| Event-Misc | 1282 | John Giffard captured and beheaded Llewellyn, Prince of Wales2 |

| Event-Misc | 2 June 1282 | King grants to him Landevery Castle, late of Rhys Vaghan, the King's enemy, charging him to keep and strengthen it.2 |

| Event-Misc | 16 August 1282 | He is to receive into the King's peace such of his own Welshmen of Penverth and Hirfren as he shall see fit.2 |

| Summoned | 30 September 1283 | Shewsbury, Parliament2 |

| Event-Misc | 1 October 1284 | He may pay the debts of Walter de Clifford, father of his late wife Matilda de Lungespee, at £20 p.a.2 |

| Event-Misc* | 30 December 1284 | Principal=Sir Humphrey VII de Bohun, Witness=Sir Walter Helion, Witness=Sir Thomas de Weyland16,17 |

| Event-Misc | 16 October 1288 | Commission re taking his deer at Brimsfield, whilst in Wales for the King2 |

| Event-Misc | 8 February 1290 | Grant of the corpus of Dynevor Castle for life as a refuge for himself and his men2 |

| Event-Misc | 18 July 1290 | Pardoned on 500 m. fine of all trespasses of vert and venison in Feckenham Forest to 7 Apr last2 |

| Event-Misc | 14 June 1294 | He was excepted from service in Gascony2 |

| Title* | Lord Gifford of Brimsfield1 | |

| Feudal* | 5 June 1299 | Manors of Brisfield, Bagworthy, Stoke Giffard, Stonhouse, and Rochampton, Glou., 5 Manors in Wilts., Corfham Castle, Salop, Clifford Castle, Here., and many other lands in England and Wales, partly inheritance of his wife Maud.2 |

Family 1 | Maud de Clifford d. bt 1282 - 1285 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Margaret (?) d. b 13 Dec 1338 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 25 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-29.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 113.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 121.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 29A-29.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 122.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 4.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 5, p. 10.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Fitz Alan 7.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 21.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 218.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 34.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 15.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 27.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 31.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 217.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 5, p. 184.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 123.

Maud de Clifford1

F, #2956, d. between 1282 and 1285

| Father* | Walter de Clifford2,3 d. c 23 Dec 1263 | |

| Mother* | Margaret verch Llywelyn2,4 d. a 1268 | |

Maud de Clifford|d. bt 1282 - 1285|p99.htm#i2956|Walter de Clifford|d. c 23 Dec 1263|p99.htm#i2958|Margaret verch Llywelyn|d. a 1268|p99.htm#i2959|||||||Llewelyn ap Iorwerth "the Great"|b. 1173\nd. 11 Apr 1240|p99.htm#i2961|Joan of Wales|b. b 1200\nd. 30 Mar 1236|p99.htm#i2962| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | after 30 April 1244 | Groom=Sir William Longespee III1,5 |

| Marriage* | circa 1257 | 1st=Sir John Gifford1,6 |

| Marriage | 1271 | Conflict=Sir John Gifford7 |

| Death* | between 1282 and 1285 | 1 |

| Death | before 12 October 1284 | 3 |

| Name Variation | Matilda7 | |

| Event-Misc* | Maud de Clifford inherited Corfham Castle, which was given to her ancestor, Walter de Clifford by King Henry II for love of his daughter, the Fair Rosamond, Principal=Walter de Clifford4 | |

| Event-Misc* | 10 March 1271 | Commission re complaint by Maud Longespe, King's Baroness, that Jn. Giffard abducted her at Kaneford Manor, took her against her will to his castle at Brinsmead and detained her there. John says that she consented, and has made fine in 300 m. for her marriage, already contracted. She is infirm and cannot come., Principal=Sir John Gifford3 |

| Event-Misc | 8 October 1281 | John and Matilda nominate attorneys in Ireland, Principal=Sir John Gifford3 |

| Event-Misc* | 10 May 1322 | Grant to Hugh le Despenser, sen., reversion of Manors in Wilts. held by Margaret, wid of Jn. Giffard sen., Principal=Sir Hugh le Despenser8 |

Family | Sir John Gifford b. c 1232, d. 28 May 1299 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 9 Apr 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-29.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-28.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 113.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 122.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 29A-29.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 121.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 114.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 123.

Sir William Longespee III1

M, #2957, d. before 3 January 1257

| Father* | Sir William de Longespée2 b. c 1208, d. 7 Feb 1249/50 | |

| Mother* | Idoine de Camville2,3 b. b 1205, d. between 01 Jan 1250/1-21 Sep | |

Sir William Longespee III|d. b 3 Jan 1257|p99.htm#i2957|Sir William de Longespée|b. c 1208\nd. 7 Feb 1249/50|p228.htm#i6831|Idoine de Camville|b. b 1205\nd. between 01 Jan 1250/1-21 Sep|p231.htm#i6914|Sir William Longespée|b. 1176\nd. 7 Mar 1225/26|p135.htm#i4028|Ela d' Evereux|b. 1187\nd. 24 Aug 1261|p135.htm#i4029|Richard d. Camville|d. b 1226|p234.htm#i6995|Eustacia Basset|d. 1215|p234.htm#i6996| | ||

| Marriage* | after 30 April 1244 | 1st=Maud de Clifford1,2 |

| Death* | before 3 January 1257 | from injuries received 4 Jun 1256 during a tournament at Blyth, Notts.1,4,5 |

| Title | Earl of Salisbury2 |

| Last Edited | 12 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-29.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Longespée 4.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 121.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 131.

Walter de Clifford1

M, #2958, d. circa 23 December 1263

| Marriage* | after 1233 | Principal=Margaret verch Llywelyn1,2 |

| Death* | circa 23 December 1263 | 1,3 |

| Residence* | Clifford's Castle, Herefordshire, England1 |

Family | Margaret verch Llywelyn d. a 1268 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 11 Jun 2005 |

Margaret verch Llywelyn1,2

F, #2959, d. after 1268

| Father* | Llewelyn ap Iorwerth "the Great"3,4,2,5 b. 1173, d. 11 Apr 1240 | |

| Mother* | Joan of Wales3,4 b. b 1200, d. 30 Mar 1236 | |

Margaret verch Llywelyn|d. a 1268|p99.htm#i2959|Llewelyn ap Iorwerth "the Great"|b. 1173\nd. 11 Apr 1240|p99.htm#i2961|Joan of Wales|b. b 1200\nd. 30 Mar 1236|p99.htm#i2962|Iorwerth D. ap Owain Gwynedd|d. c 1174|p103.htm#i3082|Marared ferch Madog|b. c 1134|p103.htm#i3083|John Lackland|b. 27 Dec 1166\nd. 19 Oct 1216|p54.htm#i1620|Clementia (?)||p150.htm#i4476| | ||

| Marriage* | circa 1219 | Principal=John de Braose1,4,2 |

| Marriage* | after 1233 | Principal=Walter de Clifford1,5 |

| Death* | after 1268 | 4,6 |

| Name Variation | Margaret of Wales4 |

Family | Walter de Clifford d. c 23 Dec 1263 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 11 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-28.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Wales 4.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-27.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 122.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 129.

John de Braose1

M, #2960, b. circa 1197, d. 18 July 1232

| Father* | William Braose1,2 d. 1210 | |

| Mother* | Maud de Clare1,2 b. c 1175, d. Jan 1225 | |

John de Braose|b. c 1197\nd. 18 Jul 1232|p99.htm#i2960|William Braose|d. 1210|p227.htm#i6784|Maud de Clare|b. c 1175\nd. Jan 1225|p134.htm#i4005|William de Braiose|b. c 1144\nd. 9 Aug 1211|p89.htm#i2669|Maud St. Valery "Lady of La Haie"|b. c 1148\nd. 1210|p89.htm#i2670|Sir Richard de Clare|b. c 1153\nd. bt 30 Oct 1217 - 28 Nov 1217|p69.htm#i2067|Amice of Gloucester|b. c 1160\nd. 1 Jan 1224/25|p69.htm#i2068| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1197 | 1,3 |

| Marriage* | circa 1219 | Principal=Margaret verch Llywelyn3,1,4 |

| Death* | 18 July 1232 | Brembye, Sussex, England, (fell from a horse)3,1 |

| Last Edited | 28 Apr 2005 |

Llewelyn ap Iorwerth "the Great"1

Llewelyn ap Iorwerth "the Great"1

M, #2961, b. 1173, d. 11 April 1240

| |

| |

| Father* | Iorwerth Drwyndwn ap Owain Gwynedd2,3,4 d. c 1174 | |

| Mother* | Marared ferch Madog2,3,4 b. c 1134 | |

| Mother | (?) Corbet; According to Boyer, Llywelyn's mother was English, which was hidden by the Welsh genealogists5 | |

Llewelyn ap Iorwerth "the Great"|b. 1173\nd. 11 Apr 1240|p99.htm#i2961|Iorwerth Drwyndwn ap Owain Gwynedd|d. c 1174|p103.htm#i3082|Marared ferch Madog|b. c 1134|p103.htm#i3083|Owain Gwynedd|b. c 1100\nd. 28 Nov 1170|p103.htm#i3088|Gwladws ferch Llywarch|b. c 1098|p103.htm#i3087|Madog ap Maredudd of Powys|b. c 1091\nd. c 9 Feb 1160|p103.htm#i3084|Anonyma (?)||p457.htm#i13694| | ||

| Birth* | 1173 | Dolyddelan, Wales1,3,4 |

| Marriage* | before 1200 | Bride=Gwenliann of Brynffenigi (?)3,6 |

| Marriage | before 23 March 1204/5 | by settlement dated Oct 1204, recorded Apr 1205, Bride=Joan of Wales4 |

| Marriage* | 1206 | 2nd=Joan of Wales1,3 |

| Mistress* | Principal=Tangwystl Goch (?)7,3,6 | |

| Marriage* | without issue, 1st=(?) of Chester4 | |

| Marriage* | Bride=Eve FitzWarin4 | |

| Death* | 11 April 1240 | Aberconway Abbey1,3,4 |

| Burial* | Aberconway Abbey, Conwy, Caernarvonshire, Wales4 | |