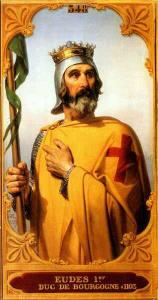

Eudes I Borel1,2

Eudes I Borel1,2

M, #3661, b. circa 1058, d. 23 March 1102/3

| Father* | Henry of Burgundy "le damoiseau de Bourgogne"1,2 b. c 1035, d. 27 Jan, between 1066 and 1074 | |

| Mother* | Sybilla of Barcelona1,3 b. c 1035, d. a 6 Jul 1079 | |

Eudes I Borel|b. c 1058\nd. 23 Mar 1102/3|p123.htm#i3661|Henry of Burgundy "le damoiseau de Bourgogne"|b. c 1035\nd. 27 Jan, between 1066 and 1074|p97.htm#i2881|Sybilla of Barcelona|b. c 1035\nd. a 6 Jul 1079|p97.htm#i2882|Robert of Burgundy "the Old"|b. c 1011\nd. 21 Mar 1076|p95.htm#i2847|Hélie of Semur-en-Auxois|b. 1016\nd. 22 Apr, after 1055|p95.htm#i2848|Berenger B. (?)|b. 1005\nd. 26 May 1035|p185.htm#i5533|Gisela d. Lluca|d. a 1079|p337.htm#i10102| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1058 | 1 |

| Marriage* | 1080 | Principal=Maud de Bourgogne (?)1,2 |

| Burial* | Abbey of Citeaux, France1 | |

| Death* | 23 March 1102/3 | Tarsus1,2 |

| Title* | Duke of Burgundy3 |

Family | Maud de Bourgogne (?) b. c 1062, d. a 1103 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 4 Dec 2004 |

Maud de Bourgogne (?)1

F, #3662, b. circa 1062, d. after 1103

| Father* | William I of Burgundy "the Great"1,2 b. c 1024, d. 11 Nov 1087 | |

| Mother* | Stephanie de Longwy1,2 b. c 1035, d. 30 Jun 1109 | |

Maud de Bourgogne (?)|b. c 1062\nd. a 1103|p123.htm#i3662|William I of Burgundy "the Great"|b. c 1024\nd. 11 Nov 1087|p118.htm#i3531|Stephanie de Longwy|b. c 1035\nd. 30 Jun 1109|p118.htm#i3532|Count Reginald I. of Burgundy|b. c 990\nd. 3 Sep 1057|p121.htm#i3617|Alisia o. N. (?)|b. c 1003\nd. a 7 Jul 1037|p121.htm#i3618|Count Adalbert I. of Longwy|b. c 1000\nd. 1048|p317.htm#i9508|||| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1062 | 1 |

| Marriage* | 1080 | Principal=Eudes I Borel1,2 |

| Death* | after 1103 | 1,3 |

| Name Variation | Matilda (?)2 | |

| Name Variation | Sibylle of Burgundy-Ivrea3 |

Family | Eudes I Borel b. c 1058, d. 23 Mar 1102/3 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 4 Dec 2004 |

Count Anselme of St. Pol1

M, #3663, b. circa 1130, d. 1174

| Father* | Hugh III (?)1 d. 1141 | |

| Mother* | Beatrix (?)1 | |

Count Anselme of St. Pol|b. c 1130\nd. 1174|p123.htm#i3663|Hugh III (?)|d. 1141|p123.htm#i3665|Beatrix (?)||p123.htm#i3666|Hugh I. (?)|d. bt 1130 - 1131|p123.htm#i3667|Elisenda d. Ponthieu||p123.htm#i3668||||||| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1130 | of Normandy, France1 |

| Marriage* | Principal=Eustachia de Champagne1,2 | |

| Death* | 1174 | 1 |

Family | Eustachia de Champagne d. a 1164 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Eustachia de Champagne1

F, #3664, d. after 1164

| Father* | Count Eustace IV of Boulogne2 b. 1131, d. 10 Aug 1153 | |

| Mother* | (?) Blois2 | |

Eustachia de Champagne|d. a 1164|p123.htm#i3664|Count Eustace IV of Boulogne|b. 1131\nd. 10 Aug 1153|p366.htm#i10967|(?) Blois||p366.htm#i10968|Stephen of Blois|b. bt 1095 - 1096\nd. 25 Oct 1154|p123.htm#i3669|Maud of Boulogne|b. c 1105\nd. 3 May 1152|p123.htm#i3670|Thibault I. of Blois|b. b 1012\nd. 29 Sep 1089|p123.htm#i3677|Alice d. Crepi|d. 12 May 1100|p205.htm#i6136| | ||

| Birth* | of Champagne, France1 | |

| Marriage* | Principal=Count Anselme of St. Pol1,3 | |

| Death* | after 1164 | 1 |

| Name Variation | Eustachie4 |

Family | Count Anselme of St. Pol b. c 1130, d. 1174 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Hugh III (?)1

M, #3665, d. 1141

| Father* | Hugh II (?)1 d. bt 1130 - 1131 | |

| Mother* | Elisenda de Ponthieu1 | |

Hugh III (?)|d. 1141|p123.htm#i3665|Hugh II (?)|d. bt 1130 - 1131|p123.htm#i3667|Elisenda de Ponthieu||p123.htm#i3668|Manasses o. S. P. (?)|d. a 1056|p187.htm#i5581||||Count Enguerrand I. of Ponthieu|d. 9 Dec 1046|p199.htm#i5945|Adele o. H. (?)||p148.htm#i4417| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Beatrix (?)1 | |

| Death* | 1141 | 1 |

Family | Beatrix (?) | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Beatrix (?)1

F, #3666

| Marriage* | Principal=Hugh III (?)1 |

Family | Hugh III (?) d. 1141 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Hugh II (?)1

M, #3667, d. between 1130 and 1131

| Father* | Manasses of St. Pol (?)1 d. a 1056 | |

Hugh II (?)|d. bt 1130 - 1131|p123.htm#i3667|Manasses of St. Pol (?)|d. a 1056|p187.htm#i5581||||Roger (?)|d. 13 Jun 1067|p187.htm#i5583|Hadwide o. H. (?)||p187.htm#i5584||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Elisenda de Ponthieu1 | |

| Death* | between 1130 and 1131 | 1 |

Family | Elisenda de Ponthieu | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Elisenda de Ponthieu1

F, #3668

| Father* | Count Enguerrand I of Ponthieu1 d. 9 Dec 1046 | |

| Mother* | Adele of Holland (?)1 | |

Elisenda de Ponthieu||p123.htm#i3668|Count Enguerrand I of Ponthieu|d. 9 Dec 1046|p199.htm#i5945|Adele of Holland (?)||p148.htm#i4417|Count Hugh I. of Ponthieu|d. 4 Jul 1000|p199.htm#i5947|Gisela o. F. (?)||p199.htm#i5948||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Hugh II (?)1 |

Family | Hugh II (?) d. bt 1130 - 1131 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Stephen of Blois1

Stephen of Blois1

M, #3669, b. between 1095 and 1096, d. 25 October 1154

| |

| |

| Father* | Count Stephen III of Blois2,3 b. 1045, d. 13 Jul 1102 | |

| Mother* | Adela of Normandy2,4,3 b. 1062, d. 8 Mar 1108 | |

Stephen of Blois|b. bt 1095 - 1096\nd. 25 Oct 1154|p123.htm#i3669|Count Stephen III of Blois|b. 1045\nd. 13 Jul 1102|p123.htm#i3673|Adela of Normandy|b. 1062\nd. 8 Mar 1108|p123.htm#i3674|Thibault I. of Blois|b. b 1012\nd. 29 Sep 1089|p123.htm#i3677|Garsinde d. M. (?)|d. 10 May 1100|p123.htm#i3678|William I. of Normandy "the Conqueror"|b. 1027\nd. 9 Sep 1087|p59.htm#i1768|Maud of Flanders|b. 1032\nd. 3 Nov 1083|p59.htm#i1769| | ||

| Birth* | between 1095 and 1096 | Blois, France2,1 |

| Marriage* | 1125 | Principal=Maud of Boulogne2,1 |

| Death* | 25 October 1154 | Dover, Kent, England2,1 |

| Burial* | Faversham Abbey, Dover, Kent, England2 | |

| Hume* | Witness=Matilda Empress of England5 | |

| Dickens* | Witness=Matilda Empress of England6 | |

| DNB* | Stephen (c.1092-1154), king of England, was the third son of Étienne (VI), count of Blois-Chartres, and Adela, daughter of William I. Stephen's father was one of the leaders of the first crusade, and achieved some notoriety for not coming to the relief of the besiegers of Antioch in 1098, and returning home. He went back to Jerusalem in 1101 and in 1102 he was killed at the battle of Ramlah. In one of his letters home from crusade Étienne bade Adela ‘keep well, govern your land excellently, and deal with your sons and your men honourably’ (Davis, 3). Adela did all these things: she lived until 1137, when she died as a nun at Marcigny, proved an admirable administrator, and provided well for her sons. The sons were a remarkable group of men, and of them all Stephen was to prove the most adventurous. Early career to 1125 Stephen was probably born about 1092, but it is not until the period 1100–10 that he is mentioned in charter attestations. The earliest of these was to a charter of not later than 1101 in favour of the cathedral of Chartres, with his elder brothers, Guillaume and Thibaud; and he occurs with them also c.1102 in a charter for the abbey of Molesme, identified as ‘their brother’ (Laurent, 2, no. 18). It was the second son, Thibaud, who became count of Blois in 1107; and c.1108 Adela issued a charter for the abbey of Conques with Thibaud ‘and my other sons’ (Desjardins, no. 486). The boys' schoolmaster was Guillaume the Norman, mentioned in 1107 as recently dead. The fourth son, Henry de Blois, was sent as a monk to Cluny. In 1109 and 1110, first at Chartres and then at Étampes, Stephen attested a diploma for the abbey of Bonneval as ‘the brother of the count of Blois’ (Bautier and Dufour, 1, no. 46). In all these charters Stephen appears in a family context, and his position in the world was defined by his relationship to other members of his family. He was particularly closely identified with Thibaud (who died in 1152) throughout their careers. He was, however, to make his own way within the Anglo-Norman world. The responsibility for this lay with Henry I, whom Stephen would succeed as king of England. Stephen first occurs in this new context in 1113, in documents relating to the monastery of St Evroult, suggesting that he had by this time been appointed as count of Mortain. At the same time, or shortly thereafter, he acquired other lands in England, including the honours of Eye and Lancaster; and after 1120 a part of the honour of Eudo Dapifer. Mortain was a frontier lordship, and Stephen was brought almost immediately into warfare with the Capetians and the count of Anjou, one phase of which lasted from 1116 to 1119. In this conflict the ambition of the house of Blois, Stephen's family, and that of Henry I, Stephen's lord for his large estates, were intertwined. Stephen was active throughout this period as a military commander, coming ‘at the head of a host’ to protect Brie in Thibaud's absence (Suger, 184–5), and arriving ‘with a force of knights’ to rescue Thibaud at L'Aigle early in November 1118 (Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 6.204–5). This was followed by an engagement at Alençon, an important border fortress, which commanded the main route from Anjou into Normandy. According to Orderic Vitalis, Sées and Alençon, and a number of border castles, were given by Henry I, after the forfeiture of Robert de Bellême, first to Count Thibaud. Thibaud then ‘with the king's permission granted that honour to his brother Stephen in return for his share of the ancestral inheritance in France’ (Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 6.196–7). For Stephen this was to prove a poor bargain. The townsmen of Alençon rebelled against their treatment by Stephen's garrison, were forced to give hostages, and called for help from Foulques, count of Anjou. Foulques came promptly and besieged the castle, and when Stephen and Thibaud, ‘eager for glory’ (Halphen and Poupardin, 156), brought up troops to relieve it they were defeated in battle outside the town walls. Alençon surrendered to the count of Anjou, who claimed a major victory, and Stephen's interest in it ceased. In the following year Stephen was one of those in command of ‘a very large force of Normans’ who attacked and burned Évreux (Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 6.228–9). He was with the royal court when it crossed from Normandy into England in late November 1120. On this crossing the White Ship went down, and the king's only legitimate son, William, was drowned. Stephen had disembarked from the ship, shortly before it sailed, ‘because he was suffering from diarrhoea’ (Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 6.306–7). Stephen was in England in December 1120 and in January 1121, when the king married again, but the charters of the early 1120s show him mainly in the context of Normandy. Count of Boulogne, 1125–1135 In 1125 Stephen was married to Matilda, the daughter and heir of Eustace (III), count of Boulogne. Boulogne was a small county within Flanders, and so formally subject to the king of France, but it was largely autonomous, and the counts of Boulogne had considerable estates in south-east England. Stephen's marriage moved him to the centre of Anglo-Norman political life. It may be that about the time that his marriage was being arranged Stephen was Henry I's preferred successor: he was Henry's protégé; he was a grandson of William the Conqueror; and he was not William Clito, the son of Robert Curthose, duke of Normandy (Henry I's eldest brother), whom many favoured but whom Henry would under no circumstances accept. The situation changed when Matilda, Henry's daughter, empress of Germany, was widowed in 1125. In the following year the empress was brought back to England, and on 1 January 1127 at London a great council of magnates accepted that Matilda should be Henry's successor. The king insisted that the magnates swear an oath in support of the empress's claims, and Stephen was the first lay noble to do so. This was a determining event in Stephen's career: it hung over him throughout his period as king, and it haunts his reputation to this day. In March 1127 Charles the Good, count of Flanders, was assassinated, and William Clito was elected count in his place. Henry again called on Stephen as his agent, using him as his intermediary in constructing a coalition of magnates, who included the duke of Louvain and the count of Hainault, against Clito. In southern Flanders, in particular, the opposition of Stephen was troublesome for the new count: in his charter of 14 April 1127 for the burgesses of St Omer he said that when he was able to make peace with Stephen he would ensure that the burgesses secured freedom from toll at Wissant. It was only in late summer that the two men came to terms, ‘because they were kinsmen’ (Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 6.372–3), and concluded a three-year truce. Within a year William Clito was dead, and the Empress Matilda had been married to Geoffrey, count of Anjou. Stephen remained close to the king. The pipe roll of 1129/30 records that ‘the count of Mortain’ had been pardoned geld in twenty counties, and indicates that he had urban properties in Southwark, Winchester, Bedford, and Colchester (the English centre of the honour of Boulogne). In the early 1130s he was at court on a number of occasions: at Windsor at Christmas 1132; at Woodstock, Winchester, and Westminster during 1133; and at Rouen in 1135, where he witnessed the king's enactment promulgating the Peace of God. King of England, 1135–1136 Henry I died during the night of 1 December 1135. He had never persuaded the magnates that the empress should rule in her own right; he had been unsympathetic to any suggestion that she should act as regent for her son; and so the process of election became crucial in determining who was to be king. Stephen moved rapidly: in the county of Boulogne when he heard of the king's death, he crossed immediately from Wissant to Dover, and made first for London. Here he was received by the citizens, who claimed a role in the election of the king. He went next to Winchester where his younger brother Henry had been bishop since 1129. It was Henry who was the main agent of Stephen's success, securing the support of Roger of Salisbury (d. 1139), the head of the English administration, and of William de Pont de l'Arche, the royal treasurer. Stephen made a range of promises to the church, to follow what it defined as best practice in church–state relations, including canonical election to senior church offices. The concessions made to the lay magnates were more limited, but Stephen did make a limited concession on the extent of the forest, and was reported as having promised wider reforms, including the abolition of geld. In return for this, Stephen was crowned king by Archbishop William of Canterbury on 22 December 1135. At the time of his coronation, he promised to all his men of England ‘all the liberties and good laws’ that they had enjoyed under his predecessors (Reg. RAN, 3, no. 270). On the other side of the channel the situation was initially less clear, for the barons of Normandy had elected as their ruler not Stephen but his elder brother, Thibaud of Blois; but when news of the coronation reached Normandy they accepted Stephen instead. The pope was informed of the coronation, and of the promises that had been made, and he confirmed Stephen's election on receiving news of them. The new king had solid support. He was a well-known and well-respected figure in the Anglo-Norman world, and also a very popular one: ‘when he was count’, said William of Malmesbury, ‘he had by his good nature and the way he jested, sat and ate in the company even of the humblest, earned an affection that can hardly be imagined’ (Malmesbury, 18). Henry I was buried at Reading Abbey on 5 January 1136 in Stephen's presence. On hearing of Henry's death David, king of Scots (d. 1153), had moved south and captured several important towns, including Carlisle and Newcastle. Stephen, drawing on the ample resources of the English treasury, was able to muster a large army, and moved north to Durham, where he arrived in mid-February. A settlement was reached between the two kings. David kept Carlisle. Henry, his son, was granted the honour of Huntingdon and other English lands; he did homage for these to Stephen at York; and he accompanied Stephen to England, where he was present at the Easter court. This court was a splendid affair, the most impressive in living memory. By this time all but a handful of the magnates had come to terms with the king. The most notable absentee from the Easter court was the empress's half-brother Robert, earl of Gloucester (d. 1147). He joined the royal entourage in early April as it moved up the Thames valley to Oxford; there he ‘received everything that he wanted’ (Gesta Stephani, 14–15), according to the king's party, and paid homage. At Oxford also the king issued what has become known as his charter of liberties, in which he confirmed the promises he had made at the time of his coronation, while reserving ‘my royal and lawful dignity’ (Reg. RAN, 3, no. 271). Another absentee from the court, closely identified with Henry I, was Baldwin de Revières (d. 1155), who fortified Exeter Castle against the king. Stephen conducted the siege of the castle in person. It lasted for three months, over a hot summer, after which the garrison surrendered, and was allowed to go free. This was a high-profile siege, conducted ‘before the eyes of all the barons’ (Gesta Stephani, 38–9), and the divided counsels among the magnates, and the king's leniency, were its lasting memory. Later in the year the king was at Brampton in Huntingdonshire, and he spent Christmas at Westminster. Difficulties in Normandy and England, 1137–1138 Stephen spent most of the year 1137 in Normandy. He crossed the channel in mid-March, and probably spent Easter at Rouen. At some point soon after his arrival Stephen came to Évreux to meet his brother Thibaud, and granted him a pension of 2000 marks a year, to compensate him for any claims he might still have on the English crown. In May Stephen met with the king of France, and his eldest son, Eustace, did homage for Normandy. This diplomatic activity was intended as the prelude to military endeavour. May was also the month in which Geoffrey of Anjou invaded Normandy; and in June the king came to Lisieux hoping to besiege Argentan, which the Angevins controlled. ‘His magnates, however, were opposed to a battle of this kind, and resolutely dissuaded the king from fighting’ (Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 6.484–5). The magnates were divided among themselves. The king travelled in the early months of his reign with a large number of mercenary troops, under the control of the Fleming William d'Ypres (d. 1165). Tension between them and the Normans was increased by suspicion of the loyalty of Robert of Gloucester. Robert claimed to have discovered a plot to capture him, and Archbishop Hugh of Rouen mediated between him and the king. Stephen's forces dissolved, and he was forced to conclude a truce with Geoffrey of Anjou in July. Geoffrey was also granted a pension of 2000 marks a year, and the first year's money was paid to him on the spot. There followed a desultory late summer and autumn, in which little was achieved. Stephen returned to England in December 1137. His immediate agenda in England had been set for him in Normandy, and it seems to have been instigated by the most influential of his counsellors, the Beaumont twins, Waleran, count of Meulan (d. 1166), and Robert, earl of Leicester (d. 1168). Bedford Castle was taken from Miles de Beauchamp after a five-week siege, and command of it given to Hugh Poer, younger brother of the Beaumonts. On hearing news of further Scottish incursions in Northumbria, in breach of the treaty made in 1136, Stephen again went north. Arriving early in February 1138 he drove the Scots back, and moved into and ‘harried and burned a great part of the land of the king of Scotland’ (Ric. Hexham, 155). His supply lines were overextended, however, and he returned south, spending Easter 1138 at Northampton. The beginning of the civil war, 1138–1140 ‘After Easter the abominable madness of the traitors flared up’ (Huntingdon, 712–13). There was a series of risings against the king throughout the west of England, from Geoffrey Talbot at Hereford to William de Mohun (d. 1145) at Dunster. The key defection was that of Robert of Gloucester, who renounced his fealty to Stephen, claiming a breach of the agreements made with him, and asserting the justice of the empress's cause. In May and June the king took part in the siege of Hereford, which was surrendered to him. He then moved to attack Robert of Gloucester's stronghold at Bristol. It was heavily fortified, and the siege was abandoned, the king preferring easier targets. He took Castle Cary and Harptree in Somerset, and then moved north to Shrewsbury, which also he took after a siege. Here for the first time, aware of criticisms of his leniency with rebels, Stephen executed a number of the garrison: ‘five men of rank were hanged’ (Chronicle of John of Worcester, 51). While the king was thus engaged, ‘good fortune smiled on him in another part of the realm’ (Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 6.522–3). A Scottish army under King David was halted and defeated immediately it had crossed the River Tees, by northern forces under the leadership of Archbishop Thurstan of York (d. 1140). The engagement, on 22 August 1138, became known as the battle of the Standard (named from the saints' banners, borne by local militias, mounted together as an emblem of resistance). In autumn 1138 the king returned to Westminster, where a church council was convened by the papal legate Alberic of Ostia. This met in December 1138, and appointed Abbot Theobald of Bec (d. 1161) archbishop of Canterbury. The legate, assisted by Stephen's queen, brokered a peace with the Scots, and this was subsequently ratified by the king at Nottingham shortly before Easter 1139. Although the Scots had been defeated in battle they made further gains in the peace, including Newcastle and the earldom of Northumbria. The king, it was said about this time, was prone to settle business more to the advantage of his opponents than himself. Stephen had to make concessions because his title to rule continued to be under challenge. The case for the Empress Matilda was made at the Lateran Council held in Rome at Easter 1139, her representatives arguing that Stephen was a usurper and a perjurer, and that he should be deposed. The pope adjourned the case, which was tantamount to a victory for the king. What the empress could not achieve diplomatically she now had to seek to achieve by military means. Rumours of her imminent arrival in England caused further divisions to open up within Stephen's camp. At midsummer 1139 the royal court met at Oxford. The king, on a flimsy pretext, and clearly influenced by his lay councillors (chief among them the Beaumont twins and Earl Alan of Richmond), arrested Roger of Salisbury and his two nephews, Alexander, bishop of Lincoln (d. 1148), and Nigel, bishop of Ely (d. 1169). The bishops were required to surrender their castles as security for their good behaviour. The king gained thereby, as he had planned, several strong and strategically placed castles, including Sherborne and Devizes, but he antagonized the leading churchmen, on whom up to this point he had relied heavily. Henry of Winchester, who had recently been appointed papal legate, convened a council at Winchester at the end of August 1139. The king and his supporters, chief among them Archbishop Hugh of Rouen and Aubrey (II) de Vere (d. 1141), sustained the main point of their case, that in time of war the crown should have the right to garrison strategic fortresses. Roger of Salisbury's disgrace was followed shortly afterwards by his death in December 1139. Stephen moved quickly to Salisbury, confiscated the bishop's treasure, conveniently piled up on the high altar of the cathedral church, and spent Christmas there. Stephen now confronted a direct challenge to his crown, from the empress in person. She had landed in the autumn of 1139, with Robert of Gloucester, and sought refuge at Arundel with Henry I's widow, Adeliza of Louvain (d. 1151). Stephen moved along the south coast from Corfe, which was held against him by Baldwin de Revières, to confront the threat. Adeliza withdrew her protection. Henry of Winchester, always sure of his opinion and subtle in arguing its acceptance, persuaded the king to allow the empress a safe conduct to Bristol, to help contain the Angevin threat in one place. This reasoning was a good deal too subtle for most who heard the story of the empress's escape: ‘quite incredible’ was the view of a source normally supportive of the king (Gesta Stephani, 88–9). While the empress was allowed to strengthen her grip on the west country, Stephen tried, with only limited success, to weaken his opponents in other areas. His itinerary in the first six months of 1140 gives an indication of how after the empress landed he lost the political initiative, and was thereafter ‘dragged hither and thither all over England’ (Gesta Stephani, 68–9). He commemorated Henry I's anniversary at Reading early in January; he besieged Bishop Nigel at Ely, and drove him from his diocese; he then marched the length of England to Cornwall, where the empress had appointed her half-brother Reginald as earl. Probably at Easter Stephen was at Winchester, and then returned to Worcester, where he had been on a number of occasions both in 1138 and 1139, having granted the earldom to Waleran, count of Meulan. He then travelled via Oxford to London, where he was at Whitsuntide, with only the most exiguous court to celebrate the feast. This was followed by an expedition to East Anglia, where the king took Hugh Bigod's castle at Bungay. The king was responding to emergencies as they arose. The battle of Lincoln and the loss of Normandy, 1141–1144 With the west country lost to the empress, and with the Scots in control of the northern counties of England, the north midlands became established as the frontier zone between Stephen and his opponents. The key figure in the region was Ranulf (II), earl of Chester (d. 1153). Ranulf inherited through his mother, the Countess Lucy, claims to the castle of Lincoln. Shortly before Christmas 1140 the king met Ranulf at Lincoln and went some way to accepting these claims. Shortly after the feast day, however, acting on complaints from the citizens, Stephen returned to Lincoln and commenced a siege of the castle. Robert of Gloucester (Earl Ranulf's brother-in-law) brought forces from the west country, including ‘a dreadful and unendurable number of Welsh’ (Gesta Stephani, 110–11). There followed the one significant set-piece battle of the reign, the battle of Lincoln, fought on 2 February 1141. The king had a large army, but not all his supporters expected to fight, and many of them fled the field. The king, dismounted, fought bravely, wielding a double-headed Norse axe to good effect, and gained some renown thereby; but he was captured, and, having been brought before the empress, was taken to Bristol Castle. There he was kept in increasingly strict confinement. The expectation was that Stephen's captivity would be permanent. In this expectation the empress was accepted by the church as legitimate ruler, and given the title ‘lady of the English’ (domina Anglorum) . Those acting for Stephen, most notably his queen, sought his release, on condition that he enter religion or remain abroad; and, with more confidence, sought the grant to Eustace of the lands his father had held before he became king. The empress's intransigence on this matter was one factor which drew the legate back to his brother's side. Having followed Stephen's path to the crown, taking the two capital cities of Winchester and London, the empress was driven from each in turn. In the retreat from Winchester in mid-September Robert of Gloucester was captured. After complex negotiations it was agreed that the king and the earl be released in exchange one for another, each party thereafter to maintain its cause as it had done before. Stephen was released on 1 November, and early in December a further church council restored him to power and excommunicated his opponents, ‘excepting only the lady of the Angevins herself’ (Malmesbury, 63). Stephen spent Christmas 1141 at Canterbury, and the routine crown wearing on the feast day took on a new significance. The king had come once more into his kingdom. If King Stephen had regained England, however, he was in the process of losing Normandy. He had had no effective control of the duchy since 1137, and his chief Norman agents had become sucked into the civil war in England: these included William d'Ypres, Richard de Lucy (d. 1179), and William de Roumare (d. 1161). Orderic wrote movingly and at length of the deteriorating condition of the duchy: ‘she suffered continually from terrible disasters and daily feared still worse, for she saw to her sorrow that the whole province was without an effective ruler’ (Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 6.492–5). The Normans, however, resisted the Angevins until they had news of Stephen's capture at the battle of Lincoln. This was the turning point: ‘when he had news that his wife had won the day’ (Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 6.546–7), Geoffrey of Anjou invaded the duchy again, and invited its magnates to accept him. Again they turned to Thibaud of Blois. When he declined, many of them (most notably Waleran, count of Meulan) felt they had no choice but to come to terms. The conquest of Normandy involved several campaigns. In 1142 Geoffrey captured Lower Normandy, the centre and west of the county, including Stephen's own lordship, the county of Mortain, in taking which he was assisted by Robert of Gloucester. In 1143 he moved through Upper Normandy, and in January 1144 he came to Rouen, where in April he was invested as duke of Normandy. His title was accepted by the church and by the French king. Stalemate in England, 1142–1146 Geoffrey of Anjou's control of Normandy was never challenged by Stephen, who struggled to maintain an effective lordship within England. The empress's party remained strongly in control of Bristol and Gloucester, and since the majority of the marcher lords supported her the king had no influence in Wales. The Gesta Stephani describes the west country as a region of peace under the lordship not of the king but of Robert of Gloucester. A similar situation applied in the northern counties, where English lordship was disputed by the Scots. The treaty of 1139 had allowed the northern baronage to accept the lordship of the Scottish king, ‘and this many of them did’ (Ric. Hexham, 177–8). David of Scots issued his own coin at Carlisle and Newcastle, just as the empress did at Cardiff, Bristol, and elsewhere. Stephen was only secure in south-east England, where he had the support of the towns and enjoyed a strong territorial lordship. Only here could he collect taxes; and, since money and power were synonymous, only here could he maintain his regality. With his lordship restricted, and with his financial backing severely depleted, Stephen needed the support of the magnates if he was to make any headway. To do this it was essential that he harness their private ambitions to his own ends. In the 1140s, although he had some isolated successes, he failed in this overall objective. His first campaign after his release, in the early months of 1142, was in Yorkshire, where he sought to impose his authority on the local earls, William d'Aumale, earl of York (d. 1179), and Alan of Brittany, earl of Richmond. This was cut short by illness, the king being detained at Northampton between Easter and Whitsun, and forces he had mustered there had to be dispersed. It is interesting to note that the empress was reported as being indisposed at very much the same time, and tempting to suggest that each of these illnesses was as much psychological as physical. The strains of fighting a civil war were taking their toll. The empress was now based at Oxford, and it was there that hostilities were resumed. Stephen, having earlier taken the earl of Gloucester's castle at Wareham in Dorset, came to Oxford in late September 1142, and blockaded the empress within the castle. After a siege of three months, just before Christmas, the empress managed to effect her escape, and the garrison surrendered. In 1143 the campaigning moved south into Wessex. Robert of Gloucester recaptured Wareham, and Stephen's efforts to take it a second time were unsuccessful. Henry of Winchester committed troops on the king's side, but at a battle on 1 July 1143 he and the king were routed at Wilton. They escaped unharmed, but William Martel was captured, and Sherborne was surrendered to effect his release. In the autumn of 1143, with the loss of Normandy imminent, and possibly in fear of a subsequent Angevin invasion, Stephen moved against Geoffrey de Mandeville, earl of Essex and custodian of the Tower of London. Geoffrey was arrested at court at St Albans, and, following a pattern that was becoming familiar, only released when he surrendered his castles. In his place, and into several of his offices, the king promoted Richard de Lucy, who became his most influential counsellor, and later enjoyed similar status under Henry II. Mandeville on his release went into revolt, fortifying Ramsey Abbey and a number of castles within the fenland, and Stephen was forced to follow him there: this revolt collapsed with Mandeville's death in mid-September 1144. While the king was thus occupied, Robert of Gloucester's men attacked the garrisons at Malmesbury and at Oxford, royal castles whose positions rendered them exposed. In 1145 Faringdon was set up as a siege-castle against Oxford, and the king took it. After the capture of Faringdon, in the view of some commentators, ‘the king's fortunes began to change for the better and took an upward turn’ (Huntingdon, 746–7). One of the sons of Robert of Gloucester, Philip, surrendered Cricklade to the king and accepted his authority. A more significant move was that made by Ranulf of Chester. Stephen had moved more than once to try to recapture Lincoln Castle. In 1145–6 Ranulf came to terms with the king at Stamford, and helped him to recapture Bedford Castle and to attack Wallingford. He sought the king's help against the Welsh, but the residue of distrust against him among the royal courtiers led to his being arrested at Northampton, and compelled to surrender his castles. The most important of these was Lincoln, and there at the scene of his earlier defeat Stephen kept the Christmas court of 1146. The king had emerged as the stronger of two weak adversaries, who lacked the resources to mount major campaigns. Henry of Anjou versus Eustace of Boulogne, 1147–1152 In the late 1140s the accidents of mortality worked for a time in the king's favour. Robert of Gloucester died on 31 October 1147, and the empress, who had relied on him for both material and moral support, left for Normandy early in 1148. The focus of the ambition of both parties was now on the next generation. Eustace was knighted in 1146–7, and given the title count of Boulogne; he had his own household, and the opportunity to demonstrate his leadership qualities. The empress's eldest son, Henry, who was two or three years younger than Eustace, chafed to assert his own independence, and gain recognition in England that he was ‘the lawful heir’ to the throne (Gesta Stephani, 204–5). He came to England on his own initiative in 1147, attacked his renegade cousin Philip of Gloucester at Cricklade, but had no success and soon ran out of funds. It was Stephen, ‘always full of pity and compassion’ (Gesta Stephani, 206–7), who sent Henry the money to pay off his troops and return home. This escapade, revealing of both parties, went almost unnoticed. Henry returned to England again in the spring of 1149, and went north to Carlisle, where he was knighted by his uncle David, king of Scots. Ranulf of Chester was there at the same time, and in an agreement with David was granted control of the honour of Lancaster, one of Stephen's own lordships. The intention was to attack Yorkshire, and then move south, but Stephen, forewarned of this, moved an army to York, where he remained throughout August. Henry made his way south via the marches, and Eustace followed him there. Within the area under Angevin control, and particularly in Gloucestershire and Wiltshire, the king's party adopted a scorched earth policy, ‘taking and plundering everything that they found’ (Gesta Stephani, 220–1). Henry returned to Normandy early in 1150, having not materially altered the balance of power between the two sides. The lack of confidence in policy and of trust in individuals, manifest in secular affairs during the 1140s, came to spread to the church also. All parties, sick of civil war, wanted the matter settled, but they had differing views as to how this should be done. Stephen wanted Eustace to succeed, and sought to secure this by following Capetian custom, which would have allowed his son to be crowned in his lifetime. The coronation would need the support of the church, but this he could no longer rely upon, in large part because his reputation as a reformer had come into question. The promise of free election at the time of his coronation did not prevent Stephen from following custom and taking a close view of church appointments. He and Henry of Winchester actively promoted the interests of their relatives. The king's own illegitimate son Gervase was made abbot of Westminster in 1138; Henry de Sully, the son of his elder brother William, became abbot of Fécamp in 1140; and Hugh, an illegitimate son of his elder brother Thibaud, became abbot of St Benet of Hulme in 1141. Among the secular clergy whose interests were fostered, Hugh du Puiset (d. 1195), the son of his sister Agnes, was appointed treasurer of York in 1143, and became bishop of Durham in 1153, while Hugh's predecessor as treasurer of York, William Fitzherbert (d. 1154), was Stephen's candidate for the archbishopric of York after the death of Thurstan in 1140. After the loss of Henry of Winchester's legation in 1143 the easy coincidence of family and national interest proved more difficult to justify. William Fitzherbert's election to York was disputed, and in 1147 Henry Murdac (d. 1153) was consecrated despite Stephen's opposition. In the same year the king's shortlisting of the abbots of Westminster, Fécamp, and St Benet as his candidates for the vacant see of Lincoln was brushed aside by the pope, Eugenius III, ‘indignantly and with harsh language’ (Letters and Charters of Gilbert Foliot, no. 75). Stephen, blaming Archbishop Theobald for these reverses, refused to allow him to attend the Council of Rheims in March–April 1148. Theobald went none the less, and his intercession alone saved Stephen from the excommunication that the pope stood ready to pronounce. Stephen relented his opposition only early in 1152, when he accepted Henry Murdac in the hope that the papacy in return would favour the coronation of Eustace. Theobald and the English hierarchy played for time, declining to crown Eustace because this would set a precedent, which should not be done while the rights remained in dispute. The dispute was now close to resolution. The key events of the early 1150s took place within Normandy. When Henry returned from England, early in 1150, he was invested by his father as duke of Normandy. The French king, Louis VII (r. 1137–80), seeing the potential for the growth of a new power in northern France, was initially hostile, but in late August 1151 he accepted Henry's homage for the duchy. Henry immediately made preparations to invade England, but he was detained by the death of his father early in September, after which he became additionally count of Anjou. A further invasion of England was planned early in 1152, on the urgent pleas of his supporters there, who claimed the king's party were gaining the upper hand. Henry, however, was again delayed, for the marriage of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine was in the process of being annulled by the church, and in May Henry was married to Eleanor. Henry of Anjou had gone in just two years from landless adventurer to lord of half of France, but he had made many enemies, and Louis VII formed an alliance against him, which included his younger brother Geoffrey, who had claims on Anjou, and Eustace, his rival for the English crown. For a while all hung in the balance: ‘almost all of the Normans thought that Duke Henry would rapidly lose all of his possessions’ (Chronica Roberti de Torigneio in Chronicles, ed. Howlett, 4.165–6). Henry's rivals had separate ambitions, however, and his control over Normandy could not be shaken. This proved decisive. When Henry sailed for England in January 1153 he had proved himself in diplomacy, and now had the resources to back up the hereditary claim that many in England accepted. He alone offered the prospect of the reunion of England and Normandy. The treaty of Winchester and the end of the reign, 1153–1154 Stephen no longer had anything to gain by diplomacy, and he sought battle. He confronted Henry first at Malmesbury, but he found his support drifting away, and was informed that several of the leading magnates ‘had already secretly sent envoys to make their peace with the duke’ (Gesta Stephani, 234–5). Stephen was forced to make a truce, and following this Henry went first to Bristol and Gloucester, and then commenced a largely triumphal passage through the midlands. In this region Stephen was still for the most part the nominal lord, but the peace had been kept by a series of magnate treaties. The impetus towards a more general peace became irresistible. The two armies confronted each other once more at Wallingford early in August. Here the protagonists were persuaded to allow negotiations on the details of a peace to begin. It seems likely that the main outline of a peace settlement had been clear for some time, for there had been discussions in 1140, in 1141 (while Stephen was in captivity), and again in 1146. Its essential feature was that Stephen should remain king for his lifetime, for he was the anointed king, but that Henry should succeed him, since he was generally viewed as ‘the lawful heir’ (Gesta Stephani, 204–5, 214–15, 222–5). The agreement was ratified at a meeting of the two parties at Winchester on 6 November. By this time Eustace was dead, and his agreed rights to his father's territories as they had been before 1135 had passed to the last surviving son, William. The peace settlement was carefully constructed, and some parts of the agreement were set down in a written instrument. Stephen adopted Henry as his heir, and Henry then did homage to Stephen; William did homage to Henry for extensive territories that were carefully specified; and the baronage of each side did homage to Stephen and to Henry if they had not done so before. The ritual of the exchange of homages was important, for it recognized the good faith of both sides, and prevented the wholesale expropriation of the losers that so often follows from civil war. The main castles not already under Angevin control were entrusted to custodians who swore to release them to Henry on Stephen's death, and until that time, Stephen's charter concluded: ‘Everywhere in England I will act with the advice of the duke, but throughout England I will exercise royal rights’ (Reg. RAN, 3, no. 272). It was agreed also that many recently built castles, the most visible symbols of the civil war, would be destroyed, and that all foreign mercenaries should be repatriated. There were to be several meetings at which homages were sworn, and the progress of the peace reviewed. At one of these Henry protested at the slow pace of demolition of castles. For most people the clearest sign of change was the circulation of a new coinage, with its distinctive bearded effigy of the king. Henry returned to Normandy at Easter 1154. Stephen went on progress in northern England, ‘encircling the bounds of England with regal pomp, and showing himself off as if he were a new king’ (William of Newburgh, Historia rerum Anglicarum, ed. R. Howlett, Rolls Series, 1884, 94). He may already have been a sick man, for there is a distinct lack of incident and of urgency in his last months. Meetings with the count of Flanders suggest a preoccupation with the concerns of his territorial lordship. After one of these, on 25 October 1154: the king was suddenly seized with a violent pain in his gut, accompanied by a flow of blood (as had happened to him before), and after he had taken to his bed in the monks' lodgings [Dover Priory] he died. (Works of Gervase of Canterbury, 1.159) Family matters and religious patronage Stephen's queen, Matilda, had died in May 1152. This was more than a private reverse for the king, for the queen, ‘subtle and steadfast’ (Gesta Stephani, 122–3), had been his constant companion and resolute supporter. In the years of struggle she took an active role, bringing troops to besiege Dover Castle in 1138, and mustering an army on the south bank opposite London in the summer of 1141. She took a prominent part in all the peace negotiations during the reign, including those with the Scots in 1138–9. She was lady of the honour of Boulogne, and the charters she issued—of which at least thirty survive—show her own voice, at times peremptory, and her involvement in the detail of estate management. There was no call for a formal regency, other than in the particular circumstances of the summer of 1141, but the charters show an easy confidence that she could act for her husband. She was frequently in the company of Archbishop Theobald in her last years, and she was the most credible of those who argued for Eustace's succession. There is every indication, though no positive proof, that the marriage of Stephen and Matilda was close and affectionate. They had five children that are recorded, three boys and two girls. The eldest son was Eustace, who is mentioned in a charter that must date from before summer 1131. The other sons were William and Baldwin: William became Earl Warenne on his marriage to the heir of the honour c.1148 and died in 1159; Baldwin died young, and was buried in London. The daughters were Mary de Blois and Matilda. Mary was professed and died a Benedictine nun, but her career in the intervening period was not without incident: she came first to the house of Stratford atte Bow, bringing with her the manor of Lillechurch in Kent and a collection of nuns-in-waiting; evicted from there they retreated to Lillechurch, where Mary became the first prioress of a new house; after her father's death, in 1155, she became abbess of Romsey. With the death of William in 1159, however, the male line failed, and she was brought out of the cloister, made countess of Boulogne, and married to Matthew, brother of the count of Flanders, with whom she had two daughters; she then went back to the cloister, and died in 1182. Matilda's story was as sad as Mary's was colourful: born c.1134, she was betrothed two years later to Waleran, count of Meulan, but she died soon afterwards, and was buried in London. The order of birth of the children cannot be established with certainty, but Eustace was certainly the eldest son, and Matilda may have been the youngest child. A possible order is: Mary, Eustace, Baldwin, William, and Matilda. In addition three illegitimate children of Stephen are known, a distinctly modest tally by the standards of Henry I. The eldest was certainly Gervase, who cannot have been born much later than 1110, since he became abbot of Westminster in 1138, after which his mother, Dameta, was ensconced in some style in the abbey manor of Chelsea. There were also William, ‘the earl's brother’, who occurs in the entourage of William, Earl Warenne, in the 1150s, and an unnamed daughter married to Hervé, count of Léon. Stephen was a conventional man, and his piety seems to have been conventional too. As count of Mortain he was influenced by the neighbouring reformed monastery at Savigny. As lord of Lancaster he founded a Savignac house at Furness, which became the most important house of the congregation in England, and as count of Boulogne he was associated also with the Savignac foundation of Coggeshall in Essex. Several other Savignac houses were founded in England in the early part of Stephen's reign. The links with the mother house in southern Normandy, however, proved problematic when Normandy was lost to the Angevins in the early 1140s. A schism followed within the order, and it merged with the Cistercians in 1147. Stephen's church patronage was redirected. He and Matilda were already associated with the templars, and with several London houses, including Bermondsey Priory and Holy Trinity, Aldgate, where two of their children were buried. The prior of Bermondsey became the first abbot of a new Cluniac monastery at Faversham in Kent, commenced in 1147, on the model of Henry I's foundation at Reading. There Matilda was buried in 1152, there Eustace in 1153, and there Stephen in 1154. It was to be the mausoleum not of a dynasty but of a nuclear family, and its possessions needed special protection in the peace agreement of 1153. When the monasteries were dissolved in the reign of Henry VIII, Stephen's tomb was stripped for its lead, and his bones cast in the neighbouring creek. Personality and outlook Stephen had risen in the court of Henry I through high birth, loyal service, and impeccable manners. He was a model courtier. As king he was in the public eye, and a good range of chronicles allows an insight into his attitudes. He was a good-natured man, not easily given to anger. When his anger was roused it was directed at those who did not meet his standards of loyalty and proper behaviour. In 1137 in Normandy he was angry when some of the leading men left court without taking their leave of him; in 1138 the bishop of Bath was given custody of Geoffrey Talbot but then released him, and ‘when this reached the king's ears he was livid’ (Chronicle of John of Worcester, 50); he was similarly irate when the empress landed in 1139, not with her but rather with those ‘whose duty it was to guard the ports’ (Chronicle of John of Worcester, 55); while in 1146 he was recorded as highly displeased when Reginald, earl of Cornwall, who was one of his opponents, was captured while enjoying safe conduct. Stephen appears to have been a man very concerned about appearances, preoccupied with feudal etiquette, with proper behaviour in the very structured environment of the Anglo-Norman court. He was conscious of his royal dignity: his crown wearings were splendid affairs. He was particularly tenacious of rights over castles, and, granted his long apprenticeship in northern France, he may have seen these rights as being as much customary as regalian. It was in pursuit of castles that he was accused, on several occasions, of acting against the expectations of the chivalric order in arresting men at court. He agonized over such decisions. He felt personally the disloyalty of those who renounced his lordship. According to William of Malmesbury, the king would say to his supporters: ‘When they have chosen me king, why do they abandon me? By the birth of God, I will never be called a king without a throne!’ (Malmesbury, 22). If anywhere in the contemporary sources, here is the man. He never would be a king without a throne. But as his reign progressed, increasingly he became a king with little else, with the shadow not the substance of regality. Significance and reputation Stephen in the historical literature has always been seen as a weak king, at times almost a cipher, when compared with his predecessor, Henry I, and his successor, Henry II. There was no peace in his day. Early in the following reign, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle wrote memorably of the nineteen years ‘when Christ and his saints were asleep’ (ASC, 200). In the late nineteenth century, when the modern study of Stephen's reign may be said to begin, the disorders of the reign were subsumed in one word, ‘anarchy’. In subsequent scholarship the phrase ‘the anarchy’, without qualification, is invariably synonymous with the reign of Stephen. The reasons for the disorder have been much debated, from the twelfth century onwards. For Henry II, and for those who wrote while his lineage ruled England, Stephen was a usurper, who had seized power in despite of a public oath, and that alone was enough to explain his ultimate failure. The selfish ambition of the baronage, when combined with the king's weakness, would reduce England to civil war. ‘When the traitors saw that he was a mild man, and gentle, and good, and did not exact the full penalties of the law, they perpetrated every enormity’, said the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (ASC, 198–9); and this tradition of interpretation has long remained influential. ‘The barons were in earnest only for their own interests’, according to William Stubbs (1.327), and following him J. H. Round produced what was intended as an exemplary study of Geoffrey de Mandeville, ‘the most perfect and typical presentment of the feudal and anarchic spirit that stamps the reign of Stephen’ (Round, Geoffrey de Mandeville, v). In studies of the later twentieth century the barons have come to be seen less as leaders than as followers, increasingly passive observers of a power struggle between two dynasties. Reflecting this tradition of historical writing, and particularly influential in establishing a wide public interest in a messy period of English politics, have been the novels of Ellis Peters (Edith Pargeter), which deal with the adventures of her monk–detective, Brother Cadfael. Here in a surprising series of best-sellers, with the merest hints of sex, and the very minimum of necessary violence, is depicted the impact of the civil war on local communities, and the problem of loyalty for individuals when both Stephen and the empress could claim to be the legitimate successor of Henry I. Conflicts between kinsmen, as contemporaries recognized, were the most difficult of all to resolve: they were indeed the very devil. The conflict between Stephen and the empress, between Eustace and Henry, was settled by agreement not warfare; and for this all the parties, the protagonists and the baronage, can take some credit. When Henry II succeeded Stephen as king of England he had much yet to do, but in terms of his title he had nothing left to prove. Edmund King Sources Reg. RAN, vols. 2–4 · K. R. Potter and R. H. C. Davis, eds., Gesta Stephani, OMT (1976) · William of Malmesbury, The Historia novella, ed. and trans. K. R. Potter (1955) · Henry, archdeacon of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum, ed. D. E. Greenway, OMT (1996) · Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., vol. 6 · John of Salisbury, Historia pontificalis: John of Salisbury's memoirs of the papal court, ed. and trans. M. Chibnall (1956) · D. Crouch, The reign of King Stephen, 1135–1154 (2000) · R. H. C. Davis, King Stephen, 3rd edn (1990) · Dugdale, Monasticon, new edn · E. King, ed., The anarchy of King Stephen's reign (1994) · E. King, ‘Stephen of Blois, count of Mortain and Boulogne’, EngHR, 115 (2000), 271–96 [career up to 1135] · K. A. LoPrete, ‘The Anglo-Norman card of Adela of Blois’, Albion, 22 (1990), 569–89 · Letters and charters of Gilbert Foliot, ed. A. Morey and others (1967) · A. Saltman, Theobald, archbishop of Canterbury (1956) · R. Howlett, ed., Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, 1, Rolls Series, 82 (1884) · R. Hexham, ‘De gestis regis Stephani et de bello standardi’, Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, ed. R. Howlett, 3, Rolls Series, 82 (1886) · R. Howlett, ed., Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, 4, Rolls Series, 82 (1889) · ASC · Suger, abbot of St Denis, Vie de Louis VI le Gros, ed. and trans. H. Waquet (Paris, 1929) · W. Stubbs, The constitutional history of England in its origin and development, 3 vols. (1874–8) · G. C. Boon, Coins of the anarchy, 1135–54 (1988) · The chronicle of John of Worcester, 1118–1140, ed. J. R. H. Weaver (1908) · J. Hunter, ed., Magnum rotulum scaccarii, vel, Magnum rotulum pipae, anno tricesimo-primo regni Henrici primi, RC (1833) · J. H. Round, Geoffrey de Mandeville: a study of the anarchy (1892) · J. H. Round, ‘The counts of Boulogne as English lords’, Studies in peerage and family history (1901), 147–80 · B. F. Harvey, ‘Abbot Gervase de Blois and the fee-farms of Westminster Abbey’, BIHR, 40 (1967), 127–42 · L. Halphen and R. Poupardin, eds., Chroniques des comtes d’Anjou et des seigneurs d’Amboise (Paris, 1913) · G. A. J. Hodgett, ed. and trans., The cartulary of Holy Trinity Aldgate, London RS, 7 (1971) · The historical works of Gervase of Canterbury, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 73 (1879–80) · C. W. Hollister, Monarchy, magnates, and institutions in the Anglo-Norman world (1986) · J. J. Champollion-Figeac, ed., Documents historiques inédits, 5 vols. (Paris, 1841–74) · G. Desjardins, ed., Cartulaire de l'abbaye de Conques en Rouergue (Paris, 1879) · J. Laurent, ed., Cartulaires de l'abbaye de Molesme, ancien diocèse de Langres, 916–1250, 2 vols. (Paris, 1907–11) · R.-H. Bautier and J. Dufour, eds., Recueil des actes de Louis VI, roi de France (1108–1137), 4 vols. (1992–4) · D. Knowles, C. N. L. Brooke, and V. C. M. London, eds., The heads of religious houses, England and Wales, 1: 940–1216 (1972) · The chronicle of John of Worcester, 1118–1140, ed. J. R. H. Weaver (1908) Likenesses M. Paris, portrait (holding his new church at Faversham; conventional), BL, Royal MS 14.C.vii, fol. 8v · coin (issue from York, showing the king and queen facing one another), repro. in Boon, Coins of the anarchy, 1135–54, pp. 41–2 · copies of coins, AM Oxf. · impression of great seal, King's Cam. · manuscript drawing, BL, Arundel MS 48, fol. 168v [see illus.] · manuscript illumination, BL, Cotton MS Vitellius A.xiii, fol. 4v · manuscript illumination, BL, Royal MS 20 A.ii, fol. 7 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Edmund King, ‘Stephen (c.1092-1154)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/26365, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Stephen (c.1092-1154): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/263657 | |

| Name Variation | Stephen of England2 | |

| Crowned* | 26 December 1135 | King of England1 |

| Battle-Standard* | 22 August 1138 | Northallerton, Yorkshire, England, Principal=David I of Scotland "the Saint", Witness=Robert de Stuteville, Witness=Bernard de Balliol, Scots=Henry of Huntingdon, English=Robert de Lacy, English=William de Percy, English=William Peverell, Scots=Eustace FitzJohn8,9,10 |

| Battle-Lincoln | 2 February 1140/41 | Principal=Ranulph de Gernon, Stephen=John d' Eu, Stephen=Hugh Bigod, Ranulph=Robert de Caen, Stephen=William Peverell, Stephen=Sir William de Warenne, Stephen=Waleran de Beaumont11 |

| Event-Misc | April 1141 | A legatine council of the English church held at Winchester declared Stephen deposed and Maud "Lady of the English"., Principal=Matilda Empress of England12 |

| Event-Misc* | 1153 | The Treaty of Westminster specified that Stephen would be King of England for life but succeeded by Henry II, Principal=Henry II Curtmantel13 |

Family | Maud of Boulogne b. c 1105, d. 3 May 1152 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 169A-25.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 32.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 169-24.

- [S337] David Hume, History of England, Chapter VII.

- [S336] Charles Dickens, A Child's History of England.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 21.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 114.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 256.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 28.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 1.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 2.

Maud of Boulogne1

F, #3670, b. circa 1105, d. 3 May 1152

|

| Father* | Count Eustace III of Boulogne1,2 b. c 1058, d. a 1125 | |

| Mother* | Mary of Scotland1,2 d. 31 May 1116 | |

Maud of Boulogne|b. c 1105\nd. 3 May 1152|p123.htm#i3670|Count Eustace III of Boulogne|b. c 1058\nd. a 1125|p127.htm#i3806|Mary of Scotland|d. 31 May 1116|p127.htm#i3807|Count Eustace I. of Boulogne|b. c 1030\nd. c 1080|p132.htm#i3933|Ida of Lorraine|b. c 1040\nd. 13 Aug 1113|p132.htm#i3934|Malcolm I. Canmore|b. 1031\nd. 13 Nov 1093|p55.htm#i1631|Saint Margaret of Scotland|b. 1045\nd. 16 Nov 1093|p55.htm#i1630| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1105 | of Boulogne, Pas-de-Calais, France1 |

| Marriage* | 1125 | Principal=Stephen of Blois1,3 |

| Burial* | Faversham Abbey, Dover, Kent, England1 | |

| Death* | 3 May 1152 | Hedington Castle, Kent, England, Witness=Aubrey de Vere4 |

| Name Variation | Matilda3 |

Family | Stephen of Blois b. bt 1095 - 1096, d. 25 Oct 1154 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 4 Sep 2005 |

Thibault IV of Blois "The Great"1,2

M, #3671, b. 1093, d. 8 October 1152

| Father* | Count Stephen III of Blois1,2 b. 1045, d. 13 Jul 1102 | |

| Mother* | Adela of Normandy1,2 b. 1062, d. 8 Mar 1108 | |

Thibault IV of Blois "The Great"|b. 1093\nd. 8 Oct 1152|p123.htm#i3671|Count Stephen III of Blois|b. 1045\nd. 13 Jul 1102|p123.htm#i3673|Adela of Normandy|b. 1062\nd. 8 Mar 1108|p123.htm#i3674|Thibault I. of Blois|b. b 1012\nd. 29 Sep 1089|p123.htm#i3677|Garsinde d. M. (?)|d. 10 May 1100|p123.htm#i3678|William I. of Normandy "the Conqueror"|b. 1027\nd. 9 Sep 1087|p59.htm#i1768|Maud of Flanders|b. 1032\nd. 3 Nov 1083|p59.htm#i1769| | ||

| Birth* | 1093 | Blois, Loir-et-Cher, France1,2 |

| Marriage* | 1123 | Principal=Maud of Carinthia1,2 |

| Death* | 8 October 1152 | Ligny, France1,2 |

Family | Maud of Carinthia b. c 1107, d. 13 Dec 1161 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 11 May 2005 |

Maud of Carinthia1

F, #3672, b. circa 1107, d. 13 December 1161

| Father* | Engelbert II (?)2 d. 28 Apr 1142 | |

| Mother* | Utha of Putten (?)2 d. 16 Apr 1140 | |

Maud of Carinthia|b. c 1107\nd. 13 Dec 1161|p123.htm#i3672|Engelbert II (?)|d. 28 Apr 1142|p123.htm#i3675|Utha of Putten (?)|d. 16 Apr 1140|p123.htm#i3676|Count Engelbert of Lavat|d. 1 Apr 1096|p123.htm#i3679|Hedwige v. Flinsbach Schwartzenburg/|b. c 1040\nd. c 1 Jul 1112|p131.htm#i3912|Ulric (?)|d. 14 APR 1099 (PLAGUE)|p123.htm#i3681|Adelaide v. Frantenhausen|d. 24 Feb 1110|p123.htm#i3682| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1107 | 2 |

| Marriage* | 1123 | Principal=Thibault IV of Blois "The Great"2,1 |

| Death* | 13 December 1161 | Fontevault, Normandy, France2,1 |

| Name Variation | Mathilda of Sponheim1 |

Family | Thibault IV of Blois "The Great" b. 1093, d. 8 Oct 1152 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 11 May 2005 |

Count Stephen III of Blois1

Count Stephen III of Blois1

M, #3673, b. 1045, d. 13 July 1102

|

| Father* | Thibault III of Blois1,2 b. b 1012, d. 29 Sep 1089 | |

| Mother* | Garsinde du Maine (?)1 d. 10 May 1100 | |

| Mother | Alice de Crepi2 d. 12 May 1100 | |

| Mother | Gundrada (?)3 | |

Count Stephen III of Blois|b. 1045\nd. 13 Jul 1102|p123.htm#i3673|Thibault III of Blois|b. b 1012\nd. 29 Sep 1089|p123.htm#i3677|Garsinde du Maine (?)|d. 10 May 1100|p123.htm#i3678|Eudes I. of Blois|b. 990\nd. 15 Nov 1037|p122.htm#i3645|Ermengarde of Auvergne|d. a 10 Mar 1042|p122.htm#i3646|Herbert I. (?)|d. 26 Mar 1051|p157.htm#i4689|Bertha o. Chartres|d. 11 Apr 1085|p151.htm#i4515| | ||

| Birth* | 1045 | 1 |

| Birth | 1046 | 4 |

| Marriage* | 1081 | Chartres, France, Principal=Adela of Normandy1,5,4 |

| Death | 27 May 1102 | Holy Land3 |

| Death* | 13 July 1102 | Battle of Ramleh, Holy Land1 |

Family | Adela of Normandy b. 1062, d. 8 Mar 1108 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 11 May 2005 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 137-22.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 31.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 32.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 169-25.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 139-23.

Adela of Normandy1

F, #3674, b. 1062, d. 8 March 1108

| Father* | William I of Normandy "the Conqueror"2,3 b. 1027, d. 9 Sep 1087 | |

| Mother* | Maud of Flanders2,3 b. 1032, d. 3 Nov 1083 | |

Adela of Normandy|b. 1062\nd. 8 Mar 1108|p123.htm#i3674|William I of Normandy "the Conqueror"|b. 1027\nd. 9 Sep 1087|p59.htm#i1768|Maud of Flanders|b. 1032\nd. 3 Nov 1083|p59.htm#i1769|Robert I. of Normandy|b. c 1000\nd. 22 Jul 1035|p59.htm#i1770|Arlette of Falais|b. c 1003|p60.htm#i1771|Count Baldwin V. of Flanders|b. 1013\nd. 1 Sep 1067|p148.htm#i4438|Adèle of France|b. c 1003\nd. 8 Jan 1079|p148.htm#i4439| | ||

| Birth* | 1062 | Normandy, France2,1 |

| Marriage* | 1081 | Chartres, France, Principal=Count Stephen III of Blois2,4,5 |

| Death* | 8 March 1108 | Cluniac Priory of Marcigny-sur-Loire, France2 |

| Death | 1137 | 6 |

| Burial* | Caen, Normandy, France2 | |

| Name Variation | Adela of England2 | |

| (Witness) Note | "Robert treated his wife cruelly, keeping her shut up in his castle at Bellême for a long time until she escaped with the help of a faithful chamberlain, found refuge with Adela, Countess of Blois, and retired to Pontieu, never to return to her husband.", Principal=Agnes of Pontieu, Principal=Robert II de Bellême7 |

Family | Count Stephen III of Blois b. 1045, d. 13 Jul 1102 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 10 Jul 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 169-24.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 169-23.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 169-25.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 32.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 183.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 163.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 139-23.

Engelbert II (?)1

M, #3675, d. 28 April 1142

| Father* | Count Engelbert of Lavat1 d. 1 Apr 1096 | |

| Mother* | Hedwige von Flinsbach Schwartzenburg/1 b. c 1040, d. c 1 Jul 1112 | |

Engelbert II (?)|d. 28 Apr 1142|p123.htm#i3675|Count Engelbert of Lavat|d. 1 Apr 1096|p123.htm#i3679|Hedwige von Flinsbach Schwartzenburg/|b. c 1040\nd. c 1 Jul 1112|p131.htm#i3912|Siegfrid von Sponheim|d. 5 Jul 1065|p187.htm#i5585|Richardis von Pusterthal|d. 9 Jul 1072|p187.htm#i5586|Bernard v. Flinsbach||p179.htm#i5369|Cecilia Flinsbach||p179.htm#i5370| | ||

| Birth* | of Treveso, Italy and Ortenburg1 | |

| Marriage* | 1110 | Principal=Utha of Putten (?)1 |

| Death* | 28 April 1142 | Seon1 |

Family | Utha of Putten (?) d. 16 Apr 1140 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Utha of Putten (?)1

F, #3676, d. 16 April 1140

| Father* | Ulric (?)1 d. 14 APR 1099 (PLAGUE) | |

| Mother* | Adelaide von Frantenhausen1 d. 24 Feb 1110 | |

Utha of Putten (?)|d. 16 Apr 1140|p123.htm#i3676|Ulric (?)|d. 14 APR 1099 (PLAGUE)|p123.htm#i3681|Adelaide von Frantenhausen|d. 24 Feb 1110|p123.htm#i3682|(Mr.) von Augstgau||p187.htm#i5596||||Kuno v. Frantenhausen|d. c 1080|p187.htm#i5600|Mathilde v. Achalm||p321.htm#i9605| | ||

| Marriage* | 1110 | Principal=Engelbert II (?)1 |

| Death* | 16 April 1140 | Seon1 |

Family | Engelbert II (?) d. 28 Apr 1142 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Thibault III of Blois1

M, #3677, b. before 1012, d. 29 September 1089

|

| Father* | Eudes II of Blois1,2 b. 990, d. 15 Nov 1037 | |

| Mother* | Ermengarde of Auvergne1 d. a 10 Mar 1042 | |

Thibault III of Blois|b. b 1012\nd. 29 Sep 1089|p123.htm#i3677|Eudes II of Blois|b. 990\nd. 15 Nov 1037|p122.htm#i3645|Ermengarde of Auvergne|d. a 10 Mar 1042|p122.htm#i3646|Count Eudes I. of Blois|b. c 950\nd. 12 Mar 0995/6|p174.htm#i5208|Bertha of Burgundy|b. c 964\nd. a 16 Jan 1016|p174.htm#i5209|Count Robert I. of Auvergne|d. 1032|p174.htm#i5210|Ermengarde of Arles||p174.htm#i5211| | ||

| Birth* | before 1012 | 1,3 |

| Marriage* | before 1049 | Bride=Garsinde du Maine (?)1,3 |

| Marriage* | Bride=Gundrada (?)1,3 | |

| Marriage* | before 1061 | Bride=Alice de Crepi1,4,3 |

| Death* | 29 September 1089 | Epernay, France1,4,3 |

| Title* | Count of Blois and Champagne3 | |

| Name Variation | Theobald III5 |

Family 1 | Alice de Crepi d. 12 May 1100 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Garsinde du Maine (?) d. 10 May 1100 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 11 May 2005 |

Citations

Garsinde du Maine (?)1

F, #3678, d. 10 May 1100

| Father* | Herbert I (?)1 d. 26 Mar 1051 | |

| Mother* | Bertha of Chartres1 d. 11 Apr 1085 | |

Garsinde du Maine (?)|d. 10 May 1100|p123.htm#i3678|Herbert I (?)|d. 26 Mar 1051|p157.htm#i4689|Bertha of Chartres|d. 11 Apr 1085|p151.htm#i4515|Hugh I. (?)|d. 1016|p173.htm#i5169||||Eudes I. of Blois|b. 990\nd. 15 Nov 1037|p122.htm#i3645|Ermengarde of Auvergne|d. a 10 Mar 1042|p122.htm#i3646| | ||

| Birth* | Amiens, Somme, France1 | |

| Marriage* | before 1049 | 1st=Thibault III of Blois1,2 |

| Death* | 10 May 1100 | 1 |

Family | Thibault III of Blois b. b 1012, d. 29 Sep 1089 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Count Engelbert of Lavat1

M, #3679, d. 1 April 1096

| Father* | Siegfrid von Sponheim1 d. 5 Jul 1065 | |

| Mother* | Richardis von Pusterthal1 d. 9 Jul 1072 | |

Count Engelbert of Lavat|d. 1 Apr 1096|p123.htm#i3679|Siegfrid von Sponheim|d. 5 Jul 1065|p187.htm#i5585|Richardis von Pusterthal|d. 9 Jul 1072|p187.htm#i5586|Count Eberhard von Loeben|d. 1023|p187.htm#i5587|Hedwig von Pusterthal||p328.htm#i9829|Count Engelbert von Pusterthal|d. 1039|p187.htm#i5590|Luitgard o. I. (?)|d. a 1051|p187.htm#i5591| | ||

| Birth* | of Ortenburg1 | |

| Marriage* | Principal=Hedwige von Flinsbach Schwartzenburg/1 | |

| Death* | 1 April 1096 | 1 |

Family | Hedwige von Flinsbach Schwartzenburg/ b. c 1040, d. c 1 Jul 1112 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 2 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Count Adalbert I of Namur1

M, #3680, d. 1006

| Father* | Count Robert I of Namur1 d. 981 | |

| Mother* | Ermengarde of Lorraine1 | |

Count Adalbert I of Namur|d. 1006|p123.htm#i3680|Count Robert I of Namur|d. 981|p180.htm#i5371|Ermengarde of Lorraine||p327.htm#i9788|Count Berenger of Namur|d. 946|p180.htm#i5372|Symphorienne of Hainault|d. a 924|p180.htm#i5373|Otto of Lorraine|d. a 955|p327.htm#i9789|||| | ||

| Marriage* | circa 990 | Principal=Ermengarde of Lorraine1 |

| Death* | 1006 | 1 |

| Name Variation | Albert I (?)1 |

Family | Ermengarde of Lorraine b. bt 970 - 975, d. a 1022 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 2 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Ulric (?)1

M, #3681, d. 14 APR 1099 (PLAGUE)

| Father* | (Mr.) von Augstgau1 | |

Ulric (?)|d. 14 APR 1099 (PLAGUE)|p123.htm#i3681|(Mr.) von Augstgau||p187.htm#i5596||||Diepold I. (?)|d. AFT 1059/60|p187.htm#i5597|||||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Adelaide von Frantenhausen1 | |

| Death* | 14 APR 1099 (PLAGUE) | Regensburg, Germany1 |

Family | Adelaide von Frantenhausen d. 24 Feb 1110 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Adelaide von Frantenhausen1

F, #3682, d. 24 February 1110

| Father* | Kuno von Frantenhausen1 d. c 1080 | |

| Mother* | Mathilde von Achalm1 | |

Adelaide von Frantenhausen|d. 24 Feb 1110|p123.htm#i3682|Kuno von Frantenhausen|d. c 1080|p187.htm#i5600|Mathilde von Achalm||p321.htm#i9605|Henry v. Schweinfurt|d. a 1043|p179.htm#i5360|(Miss) von Sulafeld||p179.htm#i5361|Rudolph (?)|d. a 1030|p321.htm#i9606|Adelheid v. Wulfingen|d. b 1065|p321.htm#i9607| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Ulric (?)1 | |

| Birth* | of Fratenhausen and Lechsgemund, Germany1 | |

| Death* | 24 February 1110 | 1 |

| Burial* | Sulzbach, Germany1 |

Family | Ulric (?) d. 14 APR 1099 (PLAGUE) | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Philip II Augustus (?)1

Philip II Augustus (?)1

M, #3683, b. 21 August 1165, d. 14 July 1223

| Father* | Louis VII of France "the Young"1,2 b. 1121, d. 18 Sep 1180 | |

| Mother* | Alix of Champagne (?)1 b. c 1140, d. 4 Jun 1206 | |

Philip II Augustus (?)|b. 21 Aug 1165\nd. 14 Jul 1223|p123.htm#i3683|Louis VII of France "the Young"|b. 1121\nd. 18 Sep 1180|p55.htm#i1625|Alix of Champagne (?)|b. c 1140\nd. 4 Jun 1206|p121.htm#i3613|Louis V. of France "the Fat"|b. 1081\nd. 1 Aug 1137|p97.htm#i2897|Adelaide of Savoy|b. c 1092\nd. 1 Aug 1154|p97.htm#i2896|Thibault I. of Blois "The Great"|b. 1093\nd. 8 Oct 1152|p123.htm#i3671|Maud of Carinthia|b. c 1107\nd. 13 Dec 1161|p123.htm#i3672| | ||

| Birth* | 21 August 1165 | Gonesse, France1 |

| Marriage* | 28 April 1180 | Bapaume, France, Principal=Isabella of Hainault (?)1 |

| Marriage* | after 15 March 1190 | Principal=Agnes of Meran (?)1 |

| Death* | 14 July 1223 | Mantes, France1 |

| Burial* | St. Denis, France1 | |

| Title* | between 1180 and 1223 | King of France2 |

| Event-Misc* | 1188 | After some warfare, Richard did homage to Philip Augustus for his French posessions., Principal=Richard I the Lionhearted3 |

| Will* | 1222 | Witness=Jean de Brienne4 |

Family 1 | Agnes of Meran (?) d. 1201 | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | Isabella of Hainault (?) b. Apr 1170, d. 15 Mar 1990 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 3 Dec 2004 |

Isabella of Hainault (?)1

F, #3684, b. April 1170, d. 15 March 1990

|

| Father* | Baldwin VIII and V (?)1 b. 1150, d. 13 Dec 1195 | |

| Mother* | Margaret of Alsace1 b. bt 1140 - 1145, d. 12 Nov 1194 | |

Isabella of Hainault (?)|b. Apr 1170\nd. 15 Mar 1990|p123.htm#i3684|Baldwin VIII and V (?)|b. 1150\nd. 13 Dec 1195|p123.htm#i3685|Margaret of Alsace|b. bt 1140 - 1145\nd. 12 Nov 1194|p123.htm#i3686|Baldwin I. (?)|b. 1109\nd. 8 Nov 1171|p123.htm#i3687|Alice o. N. (?)|b. c 1115\nd. LATE JULY 1168|p123.htm#i3688|Dietrich I. (?)|b. 1099 or 1101\nd. 17 Jan 1168|p123.htm#i3689|Sibylla o. A. (?)|b. 1116\nd. 1167|p123.htm#i3690| | ||

| Birth* | April 1170 | Valenciennes, Hainault, France1 |

| Marriage* | 28 April 1180 | Bapaume, France, Principal=Philip II Augustus (?)1 |

| Death* | 15 March 1990 | Paris, France1 |

| Burial* | Notre-Dame, Paris, Seine, France1 |

Family | Philip II Augustus (?) b. 21 Aug 1165, d. 14 Jul 1223 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 16 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Baldwin VIII and V (?)1

M, #3685, b. 1150, d. 13 December 1195

|

| Father* | Baldwin IV (?)1 b. 1109, d. 8 Nov 1171 | |

| Mother* | Alice of Namur (?)1 b. c 1115, d. LATE JULY 1168 | |

Baldwin VIII and V (?)|b. 1150\nd. 13 Dec 1195|p123.htm#i3685|Baldwin IV (?)|b. 1109\nd. 8 Nov 1171|p123.htm#i3687|Alice of Namur (?)|b. c 1115\nd. LATE JULY 1168|p123.htm#i3688|Baldwin I. of Hainault|b. bt 1087 - 1088\nd. 1120|p124.htm#i3691|Adelaide of Gueldres||p124.htm#i3692|Godfrey (?)|b. c 1067\nd. 19 Aug 1139|p124.htm#i3693|Ermensinde o. L. (?)|b. c 1080\nd. 24 Jun 1143|p124.htm#i3694| | ||

| Birth* | 1150 | of Hainault, France1 |

| Marriage* | April 1169 | Principal=Margaret of Alsace1 |

| Death* | 13 December 1195 | Mons, France1 |

| Burial* | St. Waldtrud, Mons, France1 |

Family | Margaret of Alsace b. bt 1140 - 1145, d. 12 Nov 1194 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 30 Dec 2004 |

Citations

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

Margaret of Alsace1

F, #3686, b. between 1140 and 1145, d. 12 November 1194

| Father* | Dietrich II (?)1 b. 1099 or 1101, d. 17 Jan 1168 | |

| Mother* | Sibylla of Anjou (?)1 b. 1116, d. 1167 | |

Margaret of Alsace|b. bt 1140 - 1145\nd. 12 Nov 1194|p123.htm#i3686|Dietrich II (?)|b. 1099 or 1101\nd. 17 Jan 1168|p123.htm#i3689|Sibylla of Anjou (?)|b. 1116\nd. 1167|p123.htm#i3690|Dietrich o. A. (?)|b. 1060\nd. 23 Jan 1115|p124.htm#i3695|Gertrude o. H. (?)|b. c 1070\nd. 1117|p124.htm#i3696|Fulk V. of Anjou "the Young"|b. 1092\nd. 10 Nov 1143|p97.htm#i2898|Erembourg of Maine|d. 1126|p97.htm#i2899| | ||

| Birth* | between 1140 and 1145 | Alsace, France1 |

| Birth | circa 1150 | 2 |

| Marriage* | April 1169 | Principal=Baldwin VIII and V (?)1 |

| Death* | 12 November 1194 | Wyendahl1 |

| Burial* | Bruges1 | |

| Name Variation | Margarite of Lorraine2 |

Family | Baldwin VIII and V (?) b. 1150, d. 13 Dec 1195 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 9 Jan 2005 |

Baldwin IV (?)1

M, #3687, b. 1109, d. 8 November 1171

| Father* | Baldwin III of Hainault1 b. bt 1087 - 1088, d. 1120 | |

| Mother* | Adelaide of Gueldres1,2 | |