William Chamberlayne1

M, #1741, b. circa 1436, d. before 1471

| Father* | Richard Chamberlayne1,2,3 b. 1391, d. 1439 | |

| Mother* | Margaret Knyvet1,3 b. c 1412, d. shortly before 12 May 1458 | |

William Chamberlayne|b. c 1436\nd. b 1471|p59.htm#i1741|Richard Chamberlayne|b. 1391\nd. 1439|p56.htm#i1671|Margaret Knyvet|b. c 1412\nd. shortly before 12 May 1458|p56.htm#i1672|Sir Richard Chamberlayne|b. 1320\nd. 24 Aug 1396|p75.htm#i2232|Margaret Loveyne|b. c 1372\nd. 18 Apr 1408|p75.htm#i2233|Sir John Knyvet|b. c 1380\nd. 9 Nov 1445|p56.htm#i1673|Elizabeth Clifton|b. c 1392\nd. b 8 Dec 1461|p56.htm#i1674| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1436 | 4 |

| Probate | 1470 | Witness=Richard Chamberlayne5 |

| Death* | before 1471 | 4,3 |

| Last Edited | 6 Oct 2004 |

Citations

Maud Cromwell1

F, #1743

| Father* | Sir Ralph Cromwell1,2,3 d. 27 Aug 1398 | |

| Mother* | Maud Bernacke1,4,3 b. bt 1335 - 1338, d. 10 Apr 1419 | |

Maud Cromwell||p59.htm#i1743|Sir Ralph Cromwell|d. 27 Aug 1398|p58.htm#i1715|Maud Bernacke|b. bt 1335 - 1338\nd. 10 Apr 1419|p58.htm#i1716|Ralph de Cromwell|d. b 28 Oct 1364|p59.htm#i1744|Anice de Bellers||p59.htm#i1745|Sir John Bernacke|b. bt 1305 - 1306\nd. 20 Mar 1346|p58.htm#i1717|Joan Marmion|d. 2 Oct 1361 or 13 Oct 1361|p58.htm#i1718| | ||

| Marriage* | before 1377 | Principal=Sir William Fitzwilliam2,5,3 |

| Living* | 1415 | 3 |

| Last Edited | 20 Nov 2004 |

Citations

Ralph de Cromwell1

M, #1744, d. before 28 October 1364

| Father* | Ralph de Cromwell2,3 b. c 1292 | |

| Mother* | Joan de la Mare4,3 d. 9 Aug 1348 | |

Ralph de Cromwell|d. b 28 Oct 1364|p59.htm#i1744|Ralph de Cromwell|b. c 1292|p59.htm#i1747|Joan de la Mare|d. 9 Aug 1348|p85.htm#i2550|Sir Ralph de Cromwell|d. c 2 Mar 1299|p59.htm#i1748|||||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | 1351 | Principal=Anice de Bellers5,3,6 |

| Death* | before 28 October 1364 | 1,3 |

| Residence* | 5 |

Family | Anice de Bellers | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 13 Oct 2004 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-34.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-33.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 138-6.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-33.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-34.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 9.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 138-7.

Anice de Bellers1

F, #1745

| Father* | Roger de Bellers1,2 d. 1326 | |

Anice de Bellers||p59.htm#i1745|Roger de Bellers|d. 1326|p59.htm#i1746|||||||||||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | 1351 | Principal=Ralph de Cromwell3,4,2 |

| Name Variation | Avice3 | |

| Name Variation | Amice4 | |

| Married Name | Cromwell |

Family | Ralph de Cromwell d. b 28 Oct 1364 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 13 Oct 2004 |

Roger de Bellers1,2

M, #1746, d. 1326

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Death* | 1326 | 1 |

| Occupation | England, chief baron of the Exchequer (Edward II).3 | |

| Name Variation | Belers2 | |

| Residence* | Bunny, Nottinghamshire, England3 | |

| Occupation* | England, Chief Baron of the Exchequer under Edward I3 | |

| Residence | Bunny, Nottingham, England3 |

Family | ||

| Children | ||

| Last Edited | 13 Oct 2004 |

Ralph de Cromwell1

M, #1747, b. circa 1292

| Father* | Sir Ralph de Cromwell2,3 d. c 2 Mar 1299 | |

Ralph de Cromwell|b. c 1292|p59.htm#i1747|Sir Ralph de Cromwell|d. c 2 Mar 1299|p59.htm#i1748||||Sir Ralph de Cromwell|d. b 18 Sep 1289|p59.htm#i1751|Margaret de Somery|d. a 18 Jun 1293|p59.htm#i1749||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Principal=Joan de la Mare4,3 | |

| Birth* | circa 1292 | 3 |

Family | Joan de la Mare d. 9 Aug 1348 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 30 Aug 2004 |

Sir Ralph de Cromwell1

M, #1748, d. circa 2 March 1299

|

| Father* | Sir Ralph de Cromwell d. b 18 Sep 1289; son and heir4 | |

| Mother* | Margaret de Somery2,3 d. a 18 Jun 1293 | |

Sir Ralph de Cromwell|d. c 2 Mar 1299|p59.htm#i1748|Sir Ralph de Cromwell|d. b 18 Sep 1289|p59.htm#i1751|Margaret de Somery|d. a 18 Jun 1293|p59.htm#i1749|||||||Sir Roger de Somery|b. c 1208\nd. b 26 Aug 1273|p59.htm#i1753|Nichole d' Aubigny|b. c 1206\nd. 1240|p59.htm#i1752| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

Family | ||

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 26 Dec 2004 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-32.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-31.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 138-4.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 55-29.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 256.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 138-5.

Margaret de Somery1

F, #1749, d. after 18 June 1293

| Father* | Sir Roger de Somery3,4 b. c 1208, d. b 26 Aug 1273 | |

| Mother* | Nichole d' Aubigny2 b. c 1206, d. 1240 | |

Margaret de Somery|d. a 18 Jun 1293|p59.htm#i1749|Sir Roger de Somery|b. c 1208\nd. b 26 Aug 1273|p59.htm#i1753|Nichole d' Aubigny|b. c 1206\nd. 1240|p59.htm#i1752|Ralph de Somery|d. 1211|p86.htm#i2552|Margaret Marshal|d. a 1243|p86.htm#i2553|Sir William d' Aubigny|b. c 1165\nd. 1 Feb 1220/21|p59.htm#i1756|Mabel of Chester|b. c 1172|p59.htm#i1757| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Groom=Sir Ralph Basset of Drayton1,5,6,4 | |

| Marriage* | before 26 January 1270/71 | 2nd=Sir Ralph de Cromwell7,5,8 |

| Death* | after 18 June 1293 | as a nun9,5,10 |

| Event-Misc* | 26 January 1270/71 | He and w. Margaret claim to be coheirs of Ralph de Somery (Inq.), Principal=Sir Ralph de Cromwell11 |

| Event-Misc | 10 October 1273 | Margaret is coheir of Nichola and of Roger de Somery, dec., Principal=Sir Ralph de Cromwell11 |

| Event-Misc | 12 April 1274 | Livery to them of lands at Barwe and Caumpeden as 1.5 Kt. Fee, Principal=Sir Ralph de Cromwell11 |

Family 1 | Sir Ralph Basset of Drayton d. 4 Aug 1265 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Sir Ralph de Cromwell d. b 18 Sep 1289 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 25 Aug 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-31.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-30.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-30.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 261.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-3.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 1, p. 52.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-31.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 14.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 55-29.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 228.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 256.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-4.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 52.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 27.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 138-4.

Sir Ralph Basset of Drayton1

Sir Ralph Basset of Drayton1

M, #1750, d. 4 August 1265

|

| Father* | Baron Ralph Basset of Drayton2,3 d. bt 1254 - 1261 | |

Sir Ralph Basset of Drayton|d. 4 Aug 1265|p59.htm#i1750|Baron Ralph Basset of Drayton|d. bt 1254 - 1261|p86.htm#i2551||||Ralph Basset|d. 1211|p485.htm#i14537|||||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Death* | 4 August 1265 | Evesham, Worchestershire, England, slain at the Battle of Evesham. Burke says: "when the Earl of Leicester perceived the great force and order of the royal army, calculating upon defeat, he conjured Ralph Basset and Hugh Dispenser to retire, and reserve themselves for better times; but they bravely answered, "the if he perished, they would not desire to live."4,2,3,5 |

| Marriage* | 1st=Margaret de Somery1,3,6,7 | |

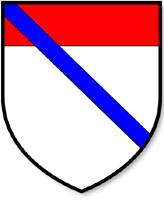

| Arms* | Or. 3 piles gu. A canton ermine (Glover).8 | |

| Occupation* | 1264 | England, M.P.2 |

| (Simon) Battle-Evesham | 4 August 1265 | Evesham, Principal=Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England, Principal=Simon VI de Montfort9,5,10 |

| Event-Misc | Michaelmas 1265 | Rob. de Tateshale, jun., seized Keteby, Olewelle, Someridiby, and Lit. Danby, Leic., which were of Ralph Basset, who was killed at Evesham. He also seized 180 acres at Estwenyr, Norf., from Wm. Constable, who was on the side of the Earl of Leicester. His bailiffs took lands and rents at Marum, Toft, and Cunyngeby from 3 persons who were not rebels. [Since he was only 16 years old at the time, I wonder if this note might refer to his father, who was also a son of Robert, so a "jun.", although the grandfather was dead by this time. -GEB], Principal=Sir Robert de Tateshal11 |

Family | Margaret de Somery d. a 18 Jun 1293 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 1 Feb 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-31.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 55-29.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-3.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-31.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 27.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 1, p. 52.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 261.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 52.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 15.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 31.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 5, p. 11.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-4.

Sir Ralph de Cromwell1

M, #1751, d. before 18 September 1289

|

| Marriage* | before 26 January 1270/71 | 2nd=Margaret de Somery2,3,4 |

| Death* | before 18 September 1289 | 1 |

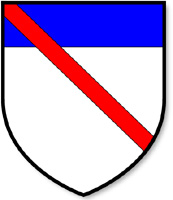

| Arms* | Arg. A chief gu. Over all a baston az. (Segar)5 | |

| Event-Misc* | 26 January 1270/71 | He and w. Margaret claim to be coheirs of Ralph de Somery (Inq.), Principal=Margaret de Somery6 |

| Event-Misc | 10 October 1273 | Margaret is coheir of Nichola and of Roger de Somery, dec., Principal=Margaret de Somery6 |

| Event-Misc | 12 April 1274 | Livery to them of lands at Barwe and Caumpeden as 1.5 Kt. Fee, Principal=Margaret de Somery6 |

| Summoned* | 1 July 1277 | serve against the Welsh, and will serve himself.6 |

| Event-Misc* | 27 June 1282 | Gift of 6 bucks from Sherwood Forest6 |

| Summoned | 30 September 1283 | Shrewsbury, Parliament6 |

| Event-Misc | 2 December 1285 | Having served with K. in Wales, has his scutage in Warw., Leic., Bucks., Glou., Notts., and Derb.6 |

| Summoned | 15 July 1287 | Gloucester, Council6 |

Family 1 | ||

| Child | ||

Family 2 | Margaret de Somery d. a 18 Jun 1293 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 26 Dec 2004 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-31.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-31.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-3.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 14.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 255.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 256.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 55-29.

Nichole d' Aubigny1

F, #1752, b. circa 1206, d. 1240

| Father* | Sir William d' Aubigny2,3,4 b. c 1165, d. 1 Feb 1220/21 | |

| Mother* | Mabel of Chester5,3,4 b. c 1172 | |

Nichole d' Aubigny|b. c 1206\nd. 1240|p59.htm#i1752|Sir William d' Aubigny|b. c 1165\nd. 1 Feb 1220/21|p59.htm#i1756|Mabel of Chester|b. c 1172|p59.htm#i1757|Sir William d' Aubigny|b. c 1139\nd. 24 Dec 1193|p86.htm#i2565|Maud de St. Hilary|b. c 1132|p86.htm#i2566|Hugh of Kevelioc|b. 1147\nd. 30 Jun 1181|p59.htm#i1758|Bertrade de Montfort|b. 1155\nd. 1227|p97.htm#i2903| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1206 | 3 |

| Marriage* | circa 1225 | Barrow, Leicestershire, England, 1st=Sir Roger de Somery6,3,4,7 |

| Death* | 1240 | Dudley Castle, Staffordshire, England3 |

| Death | before 1254 | 4 |

| Married Name | Somery D' |

Family | Sir Roger de Somery b. c 1208, d. b 26 Aug 1273 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 25 Aug 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-30.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-29.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-2.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-29.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-30.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 219.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 228.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 137-3.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 262.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 261.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 264.

Sir Roger de Somery1

M, #1753, b. circa 1208, d. before 26 August 1273

|

| Father* | Ralph de Somery2,3 d. 1211 | |

| Mother* | Margaret Marshal2 d. a 1243 | |

Sir Roger de Somery|b. c 1208\nd. b 26 Aug 1273|p59.htm#i1753|Ralph de Somery|d. 1211|p86.htm#i2552|Margaret Marshal|d. a 1243|p86.htm#i2553|Sir John de Somery|d. bt 1189 - 1199|p86.htm#i2555|Hawise Paynel|d. b 1194|p86.htm#i2554|John FitzGilbert (?)|b. c 1106\nd. b Michaelmas in 1165|p89.htm#i2641|Sybil de Salisbury|b. c 1120|p89.htm#i2642| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1208 | of Sedgley, Staffordshire, England4 |

| Marriage* | circa 1225 | Barrow, Leicestershire, England, Bride=Nichole d' Aubigny5,4,6,3 |

| Marriage* | before 1254 | 2nd=Amabil de Chaucombe7,8,4,9,10 |

| Death* | before 26 August 1273 | shortly before 26 Aug 1273, holding Manors of Clent in Staff., Bradfield, Stanford, Yngepenne, Hodicot, Hildesle, Kingeston, Cumpton, Yatingeden, and Englefield, together 8 1/4 Fees in Berks., Middelton and Abingworth as 1 1/2 Fee in Surr., Woleye, Cradleye, and Dudley with borough, Worc., Seggesley, Mere, and Swyneford in Staff., Bordesle in Warw., Newport Paynel and c. 9 1/2 Fees in Bucks., Campeden and borough, Glou., and Barrow in Leic. He was g.s. of Ralph de S., to whom K. John gave Mere Manor, Staff, and he married 1, Nicholaa de Albiniaco, and 2, Anabel. His s.h. Ralph, 18 on 24 June last ob. s. p. , and the 4 daus. of Nicholaa, viz. Margaret, Joan, Mabel, and Maud are all married.11,4,6,12 |

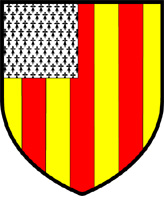

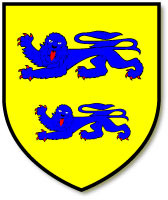

| Arms* | D'or a deux leons d'azure passans (Glover).12 | |

| Residence* | Dudley Castle, Dudley, Warwick, England13,6 | |

| Event-Misc | 1229 | He suceeded his nephew Nicholas and mande an agreement with Maurice de Gant, granting him Dudley and Sedgley for 7 years and undertaking not to marry in that term without Maurice's permission.14 |

| Event-Misc | 1230 | He was involved in the war against France14 |

| Event-Misc | 1234 | He was allied with Hubert de Burgh in rebellion against the Poitevin influence on King Henry III14 |

| Event-Misc | January 1233/34 | He was appointed to remain at Shrewsbury to maintain order14 |

| Summoned | 11 July 1245 | Chester with arms and horses14 |

| Event-Misc | 20 July 1247 | Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire, He had a grant of free warren14 |

| Feudal* | 5 November 1247 | Great Tywe, Oxfordshire, 1 carucate12 |

| Protection* | May 1253 | to Gascony14 |

| Summoned | July 1257 | Chester14 |

| Event-Misc | 1258 | He was one of 12 elected to treat with the King's Council, and one of 24 appointed by the barons14 |

| Feudal | 23 January 1260 | Stanford Manor, Berks., as 1 Kt. Fee12 |

| Note* | 1262 | Dudley, Warwick, England, built Dudley Castle without license for which he was warned6,14 |

| Summoned | 25 May 1263 | Hereford14 |

| Event-Misc* | 10 August 1263 | Roger de Somery was directed to deliver the counties of Salop and Stafford to Hamon Lestrange, Principal=Hamo le Strange14 |

| Summoned* | 16 October 1263 | the King at Windsor for Council9 |

| Event-Misc* | 16 March 1264 | Lic. for him to enclose his dwelling places of Duddeleg Manor, Staff., and of Welegh, Worc., with ditch and wall of stone and lime, and to crenellate same.9 |

| Event-Misc | 23 February 1265 | Complaint re breaking doors of his hall and damaging his Manor of Aspele, Warw.9 |

| Feudal | Michelmas 1265 | Burmingham Manor, Warw.9 |

| Event-Misc* | 19 October 1265 | Roger de Somery is married to Amabel, wid. of Gilb. de Segrave, Principal=Amabil de Chaucombe9 |

| Event-Misc | 1266 | He was one of 8 "persons of most potent nobility" chosen to draw up the "Dictum of Kenilworth"14 |

| Event-Misc | 3 August 1266 | Complaint re burning his houses at Dudley9 |

| Event-Misc | 29 September 1267 | Commissioner re peace between the King and Llwellyn ap Griffin9 |

| Event-Misc | 14 March 1268 | Roger de Somery was a Commissioner re dispute between Llewellyn, P. of Wales, and Gilb., E. of Gloucester, Witness=Sir Gilbert de Clare "the Red"9 |

| Event-Misc* | 11 November 1275 | Grant to Wm. de Valencia custody of his lands and marriage of heirs, Principal=Sir William de Valence12 |

| Event-Misc* | 6 February 1277 | Grant to Joan, wife of Wm. de Valencia, custody of Bradefeld Manor in minority of his heirs, Principal=Joan de Munchensi12 |

Family 1 | Nichole d' Aubigny b. c 1206, d. 1240 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Amabil de Chaucombe b. c 1210, d. c 1278 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 25 Aug 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-30.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 55-29.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 219.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-30.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-2.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-30.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 81-29.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 261.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 217.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 55-28.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 262.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-30.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 228.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 137-3.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 264.

Amabil de Chaucombe1

F, #1754, b. circa 1210, d. circa 1278

| Father* | Robert de Chaucombe1,2 b. c 1175 | |

| Mother* | Julian Chaucomb2 b. c 1170 | |

Amabil de Chaucombe|b. c 1210\nd. c 1278|p59.htm#i1754|Robert de Chaucombe|b. c 1175|p59.htm#i1755|Julian Chaucomb|b. c 1170|p107.htm#i3195|Hugh Chaucombe||p136.htm#i4075|Hodierne Chaucombe||p136.htm#i4076||||||| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1210 | Arundel, Sussex, England2 |

| Marriage* | before 30 September 1231 | Groom=Sir Gilbert de Segrave2,3,4,5 |

| Marriage* | before 1254 | Groom=Sir Roger de Somery1,6,2,3,5 |

| Death* | circa 1278 | 6,2,5 |

| Burial* | Chaucombe Priory, Northamptonshire, England2,5 | |

| Married Name | Somery | |

| Name Variation | Anabel Chaucomb2 | |

| Event-Misc* | 19 October 1265 | Roger de Somery is married to Amabel, wid. of Gilb. de Segrave, Principal=Sir Roger de Somery3 |

| Event-Misc* | 19 October 1265 | Amabil, widow of Gilbert de Segrave and mother of Nicholas, and heiress of Hugh de Chaucombe, founder of Chaucombe Priory, is now wife of Rog. de Sumery7 |

| Event-Misc | 2 November 1273 | She is to have £100 lands in dower, viz., Manors of Bradfield £60, Swyneford £16 18s. 4 3/4d., Clent £8 17s. 5 1/4d., Cradele £8 6s 0 3/4d., and Seggeley Park8 |

| Protection* | 1 August 1276 | over seas.7 |

| Summoned* | 1 July 1277 | serve against the Welsh7 |

| Summoned | 2 August 1282 | serve against the Welsh7 |

Family 1 | Sir Gilbert de Segrave b. c 1185, d. b 8 Oct 1254 | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | Sir Roger de Somery b. c 1208, d. b 26 Aug 1273 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 25 Aug 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-30.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 261.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 16B-26.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 217.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 81-29.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 235.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 262.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 233.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 16B-27.

Robert de Chaucombe1

M, #1755, b. circa 1175

| Father* | Hugh Chaucombe2 | |

| Mother* | Hodierne Chaucombe2 | |

Robert de Chaucombe|b. c 1175|p59.htm#i1755|Hugh Chaucombe||p136.htm#i4075|Hodierne Chaucombe||p136.htm#i4076||||||||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Julian Chaucomb2 | |

| Birth* | circa 1175 | of Chaucomb, Northamptonshire, England2 |

Family | Julian Chaucomb b. c 1170 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Sir William d' Aubigny1,2

Sir William d' Aubigny1,2

M, #1756, b. circa 1165, d. 1 February 1220/21

|

| Father* | Sir William d' Aubigny3,4,2 b. c 1139, d. 24 Dec 1193 | |

| Mother* | Maud de St. Hilary3 b. c 1132 | |

Sir William d' Aubigny|b. c 1165\nd. 1 Feb 1220/21|p59.htm#i1756|Sir William d' Aubigny|b. c 1139\nd. 24 Dec 1193|p86.htm#i2565|Maud de St. Hilary|b. c 1132|p86.htm#i2566|Sir William d' Aubigny "Pincerna (Strong Hand)"|b. 1110\nd. 12 Oct 1176|p86.htm#i2571|Adeliza of Louvain|b. 1103\nd. 23 Apr 1151|p86.htm#i2570|James de St. Hilary|b. c 1110\nd. c 1154|p86.htm#i2567|Aveline (?)||p86.htm#i2568| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Mabel of Chester5,4,2,6 | |

| Birth* | circa 1165 | of Arundel, Essex, England4 |

| Burial* | Wymondham Abbey, Wymondham, Norfolk, England4,7 | |

| Death* | 1 February 1220/21 | Cainell, near Rome, Italy, |while returning from crusade7,8 |

| Title* | 3rd Earl of Arundel8 | |

| Arms* | Gu. A lion rampant double queued or (M. Paris I)2 | |

| Name Variation | William de Albini2 | |

| Event-Misc* | 15 May 1213 | He was a favorite of King John and witnessed the king's concession of the kingdom to the Pope, Principal=John Lackland8 |

| (Barons) Magna Carta | 12 June 1215 | Runningmede, Surrey, England, King=John Lackland9,10,11,12,8,13 |

| Event-Misc* | 14 July 1217 | He joined Henry III after the royal faction won at Lincoln, had forfeiture of his possessions reversed and became justiciar., Principal=Henry III Plantagenet King of England8 |

| Event-Misc* | 1218 | He left on crusade8 |

Family | Mabel of Chester b. c 1172 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 27 Apr 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-29.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 6.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-25.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-29.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 50.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 129-1.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 8.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Longespée 3.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 3.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 56-27.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 60-28.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 34.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 132-2.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-26.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 134-2.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 29.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-2.

Mabel of Chester

F, #1757, b. circa 1172

| Father* | Hugh of Kevelioc1,2 b. 1147, d. 30 Jun 1181 | |

| Mother* | Bertrade de Montfort3,2 b. 1155, d. 1227 | |

Mabel of Chester|b. c 1172|p59.htm#i1757|Hugh of Kevelioc|b. 1147\nd. 30 Jun 1181|p59.htm#i1758|Bertrade de Montfort|b. 1155\nd. 1227|p97.htm#i2903|Ranulph de Gernon|b. c 1100\nd. 16 Dec 1153|p59.htm#i1763|Maud de Caen|b. c 1120\nd. 29 Jul 1189|p59.htm#i1762|Simon de Montfort|d. c 13 Mar 1180/81|p59.htm#i1760|Maud (?)|d. 1168|p59.htm#i1761| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Sir William d' Aubigny4,2,5,6 | |

| Birth* | circa 1172 | 2 |

| Married Name | Aubigny |

Family | Sir William d' Aubigny b. c 1165, d. 1 Feb 1220/21 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 18 May 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-28.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-28.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-29.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 6.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 50.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 8.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-26.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-2.

Hugh of Kevelioc1

M, #1758, b. 1147, d. 30 June 1181

| Father* | Ranulph de Gernon2,3 b. c 1100, d. 16 Dec 1153 | |

| Mother* | Maud de Caen2,3 b. c 1120, d. 29 Jul 1189 | |

Hugh of Kevelioc|b. 1147\nd. 30 Jun 1181|p59.htm#i1758|Ranulph de Gernon|b. c 1100\nd. 16 Dec 1153|p59.htm#i1763|Maud de Caen|b. c 1120\nd. 29 Jul 1189|p59.htm#i1762|Ranulph I. le Meschin de Briquessart|b. c 1070\nd. 17 Jan 1128/29 or 27 Jan 1128/29|p102.htm#i3036|Lucy (?)|b. c 1068\nd. 1141|p59.htm#i1764|Robert de Caen|b. c 1090\nd. 31 Oct 1147|p59.htm#i1765|Maud FitzRobert|d. 1157|p59.htm#i1766| | ||

| Birth* | 1147 | Kevelioc, Monmouthshire, Wales4,3 |

| Marriage* | 1169 | Principal=Bertrade de Montfort5,3,6 |

| Death* | 30 June 1181 | Leek, Staffordshire, England4,3,6 |

| Burial* | St. Werburg's, Chester, Cheshire, England3 | |

| Title* | Earl of Chester, Viscount of Avranches6 | |

| DNB* | Hugh [Hugh of Cyfeiliog], fifth earl of Chester (1147-1181), magnate, was the son of Ranulf (II), fourth earl of Chester, and his wife, Matilda, daughter of Robert, earl of Gloucester, the illegitimate son of Henry I. He is sometimes called Hugh of Cyfeiliog (Meirionydd), because, according to a late writer, he was born in that district of Wales. His father died on 16 December 1153, when Hugh was still under age. His inheritance, on both sides of the channel, included the hereditary viscountcies of Avranches, Bessin, and Val de Vire, the honours of St Sever and Briquessart, and the Chester earldom together with its associated honours in England and Wales, making the earl one of the greatest of all Anglo-Norman landholders. Hugh came of age in 1162, when he took seisin of his lands and received his title. He was present in 1163 at Dover for Henry II's renewal of the Flemish money fief, and also attended the Council of Clarendon in January 1164. He failed to make a return to the English survey of knight's fees in 1166, and later apparently went unassessed under the 1168 aid taken for the marriage of the king's daughter. Hugh joined the rebellion of Henry II's sons in 1173. Aided by Ralph de Fougères he utilized his great influence in the north-eastern marches of Brittany to incite the Bretons to revolt. Henry II dispatched an army of Brabant mercenaries against them. The rebels were defeated in a battle, and on 20 August were shut up in the castle of Dol, which they had captured by fraud not long before. On 23 August, Henry II arrived to conduct the siege in person. Hugh and his comrades had no provisions, and were therefore forced to surrender on 26 August on a promise that their lives and limbs would be saved. Eighty knights surrendered with them. Hugh was treated leniently by Henry, and was confined at Falaise, where the earl and countess of Leicester were also soon brought as prisoners. When Henry II returned to England he took the two earls with him. They were conveyed from Barfleur to Southampton on 8 July 1174. Hugh was probably afterwards imprisoned at Devizes. On 8 August, however, he was taken back from Portsmouth to Barfleur, when Henry II returned to Normandy. He was now imprisoned at Caen, and from there removed to Falaise. He was admitted to terms with Henry before the general peace, and witnessed the treaty of Falaise on 11 October. Hugh seems to have remained some time longer without restoration. At last, at the Council of Northampton on 13 January 1177, he received grant of the lands on both sides of the channel which he had held fifteen days before the war broke out. In March he witnessed Henry II's award in the dispute between Alfonso IX, king of Castile, and Sancho V, king of Navarre. In May, at the Council of Windsor, Henry restored to him his castles, and required him to go to Ireland, along with William fitz Audelin and others, to prepare the way for the king's son. But no great grants of Irish land were conferred on him, and he took no prominent part in the Irish campaigns. Nevertheless, Chester's increased trade with Ireland amply profited the earldom in years to come. Hugh's liberality to the church was not as great as that of his predecessors. He granted some lands in the Wirral to the abbey of St Werburgh, Chester, and made other special gifts to Stanlow Priory, St Mary's, Coventry, and the nuns of Bullington and Greenfield priories. He also confirmed his mother's grants to her foundation of Augustinian canons at Calke, Derbyshire, and those of his father to his convent of the Benedictine nuns of St Mary's, Chester. In 1171 he confirmed the grants of Ranulf to the abbey of St Stephen in the diocese of Bayeux. More substantial were his grants of Belchford church to Trentham Priory, and of Combe in Gloucestershire to the abbey of Bordesley, Warwickshire. Hugh married in 1169 Bertrada, the daughter of Simon, count of Évreux. Hugh died at Leek in Staffordshire on 30 June 1181. He was buried next to his father on the south side of the chapter house of St Werburgh's, Chester, now the cathedral. His only legitimate son, Ranulf (III), succeeded him as earl of Chester. He and his wife also had four daughters, who became, on their brother's death, coheirs of the Chester earldom. They were: Maud, who married David, earl of Huntingdon, and became the mother of John the Scot, earl of Chester from 1232 to 1237, on whose death the line of Hugh d'Avranches became extinct; Mabel, who married William d'Aubigny, earl of Arundel (d. 1221); Agnes, the wife of William Ferrers, earl of Derby; and Hawise, who married Robert de Quincy (d. 1217), son of Saer de Quincy, earl of Winchester. Hugh was also the father of several bastards, including Pagan, lord of Milton; Roger; Amice, who married Ralph Mainwaring, county justice of Chester; and another daughter, who married Richard Bacon, the founder of Rocester Abbey. T. F. Tout, rev. Thomas K. Keefe Sources G. Barraclough, ed., The charters of the Anglo-Norman earls of Chester, c.1071–1237, Lancashire and Cheshire RS, 126 (1988), 140–96 · R. C. Christie, ed. and trans., Annales Cestrienses, or, Chronicle of the abbey of S. Werburg at Chester, Lancashire and Cheshire RS, 14 (1887), 19, 28 · T. A. Heslop, ‘The seals of the twelfth-century earls of Chester’, Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, 71 (1991) [G. Barraclough issue, The earldom of Chester and its charters, ed. A. T. Thacker] · J. Tait, ed., The chartulary or register of the abbey of St Werburgh, Chester, Chetham Society, 82 (1923) · W. Stubbs, ed., Gesta regis Henrici secundi Benedicti abbatis: the chronicle of the reigns of Henry II and Richard I, AD 1169–1192, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 49 (1867), 1.161, 277 · Chronica magistri Rogeri de Hovedene, ed. W. Stubbs, 2, Rolls Series, 51 (1869), 51, 118 · R. Howlett, ed., Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, 1, Rolls Series, 82 (1884) · Jordan Fantosme’s chronicle, ed. and trans. R. C. Johnston (1981), 12–18 · Ralph de Diceto, ‘Ymagines historiarum’, Radulfi de Diceto … opera historica, ed. W. Stubbs, 1: 1148–79, Rolls Series, 68 (1876), 378 · G. Barraclough, The earldom and county palatinate of Chester (1953) · G. Ormerod, The history of the county palatine and city of Chester, 2nd edn, ed. T. Helsby, 1 (1882), 29 · T. K. Keefe, ‘King Henry II and the earls: the pipe roll evidence’, Albion, 13 (1981), 191–222 · M. T. Flanagan, Irish society, Anglo-Norman settlers, Angevin kingship: interactions in Ireland in the late twelfth century (1989), 75, 144, 168, 291 · T. K. Keefe, Feudal assessments and the political community under Henry II and his sons (1983) · English historical documents, 2nd edn, 2, ed. D. C. Douglas and G. W. Greenaway (1981), 449, 767 · Pipe rolls, 20 Henry II, 21 · W. Dugdale, The baronage of England, 2 vols. (1675–6) · L. Delisle and others, eds., Recueil des actes de Henri II, roi d'Angleterre et duc de Normandie, concernant les provinces françaises et les affaires de France, 4 vols. (Paris, 1909–27), vol. 1, p. 380; vol. 2, p. 23 · T. Stapleton, ed., Magni rotuli scaccarii Normanniae sub regibus Angliae, 2 vols., Society of Antiquaries of London Occasional Papers (1840–44) · H. Hall, ed., The Red Book of the Exchequer, 3 vols., Rolls Series, 99 (1896) · J. W. Alexander, Ranulf of Chester: a relic of the Conquest (1983) Likenesses seal, repro. in Ormerod, History of the county palatine, 1.32 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press T. F. Tout, ‘Hugh , fifth earl of Chester (1147-1181)’, rev. Thomas K. Keefe, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14059, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Hugh (1147-1181): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/140597 | |

| (Witness) Event-Misc | He was given Fallybrome by Hugh, 2nd Earl of Chester, Principal=Sir Richard de Phytun8 | |

| Name Variation | Hugh de Meschines3 | |

| Event-Misc* | 13 July 1174 | Alnwick, He joined the rebellion against Henry II and was taken prisoner6 |

| Note* | Normandy, France, Vicomte d'Avranches4 |

Family 1 | ||

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Bertrade de Montfort b. 1155, d. 1227 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-28.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-27.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 125-28.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-28.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 50.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 107.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Wales 4.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 127-28.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 125-29.

Bertrade de Montfort1

F, #1759, b. circa 1060, d. 14 February 1117

| Father* | Simon I de Montfort2,3 b. c 1026, d. 25 Sep 1087 | |

| Mother* | Agnes d' Evreux2,3 b. c 1030 | |

Bertrade de Montfort|b. c 1060\nd. 14 Feb 1117|p59.htm#i1759|Simon I de Montfort|b. c 1026\nd. 25 Sep 1087|p97.htm#i2904|Agnes d' Evreux|b. c 1030|p97.htm#i2905|Amauri de Montfort|d. 1053|p113.htm#i3367|Bertrarde du Gommets|d. a 1051/52|p113.htm#i3368|Richard d' Evereux|b. 986\nd. 13 Dec 1067|p113.htm#i3369|Estephania de Barcelona|d. 1051|p113.htm#i3370| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1060 | Montfort l'Amauri, France3 |

| Marriage | 1089 | 5th=Count Fulk IV of Anjou "Rechin"3,4 |

| Marriage* | 1090/91 | Conflict=Count Fulk IV of Anjou "Rechin"2,5 |

| Divorce* | 15 April 1092 | Principal=Count Fulk IV of Anjou "Rechin"4 |

| Marriage* | 15 May 1092 | Groom=Philip I of France3,4 |

| Death* | 14 February 1117 | Fontevrault, France3,4 |

| Name Variation | Beatrice (?)2 |

Family 1 | Philip I of France b. 1053, d. 29 Jul 1108 | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | Count Fulk IV of Anjou "Rechin" b. 1043, d. 14 Apr 1109 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Jul 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-28.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 118-23.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 159.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 198.

Simon de Montfort1

M, #1760, d. circa 13 March 1180/81

| Father* | Amaury III de Montfort2,3 b. c 1070, d. a 19 Apr 1136 | |

| Mother* | Agnes de Garlande2 d. 1143 | |

Simon de Montfort|d. c 13 Mar 1180/81|p59.htm#i1760|Amaury III de Montfort|b. c 1070\nd. a 19 Apr 1136|p113.htm#i3365|Agnes de Garlande|d. 1143|p113.htm#i3366|Simon I. de Montfort|b. c 1026\nd. 25 Sep 1087|p97.htm#i2904|Agnes d' Evreux|b. c 1030|p97.htm#i2905|Anselm d. Garland|b. c 1069\nd. 1118|p113.htm#i3375|(?) de Monthery|b. c 1073|p113.htm#i3376| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Maud (?)4,2 | |

| Burial* | Evreux Cathedral, France2 | |

| Death* | circa 13 March 1180/81 | 4,2 |

| Burial | Évreux Cathedral, Normandy, France3 | |

| Title* | Count of Évreux3 | |

| Name Variation | Simon III de Montfort2 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1159 | He was a vassal of both the King of France and the King of England in Normandy. He sided with Henry II in the war between those kings. Since Simon controlled the castles of Rochefort and Montfort, Louis was forced to make a truce, since communications between Paris, Orleans and Etampes were cut5 |

| Event-Misc | 1175 | He joined the revolt of Young King Henry against his father, but was captured by the Count of Flanders who successfully besieged the castle of Aumale5 |

| Event-Misc | 1177 | He attended the treaty of Ivry5 |

Family | Maud (?) d. 1168 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 22 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 125-28.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 159.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 125-28.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 160.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 126-28.

Maud (?)1

F, #1761, d. 1168

| Marriage* | Principal=Simon de Montfort2,3 | |

| Death* | 1168 | 3 |

| Married Name | Montfort2 |

Family | Simon de Montfort d. c 13 Mar 1180/81 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Maud de Caen1

F, #1762, b. circa 1120, d. 29 July 1189

| Father* | Robert de Caen2,3 b. c 1090, d. 31 Oct 1147 | |

| Mother* | Maud FitzRobert2,3 d. 1157 | |

Maud de Caen|b. c 1120\nd. 29 Jul 1189|p59.htm#i1762|Robert de Caen|b. c 1090\nd. 31 Oct 1147|p59.htm#i1765|Maud FitzRobert|d. 1157|p59.htm#i1766|Henry I. Beauclerc|b. 1068\nd. 1 Dec 1135|p55.htm#i1629|Nesta verch Rhys|b. c 1073|p117.htm#i3498|Robert FitzHamon|b. c 1050\nd. Mar 1107|p59.htm#i1767|Sybil Montgomery|b. c 1058\nd. 1107|p117.htm#i3499| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1120 | 3 |

| Marriage* | circa 1141 | Principal=Ranulph de Gernon4,3 |

| Death* | 29 July 1189 | 4,3 |

| DNB* | Matilda, countess of Chester (d. 1189), magnate, was the granddaughter of Henry I by his illegitimate son Robert, earl of Gloucester (d. 1147), and Sibyl, the daughter of Roger de Montgomery, earl of Shrewsbury (d. 1157). Before 1135 she married Ranulf (II), fourth earl of Chester (d. 1153), with whom she had a son, Hugh (d. 1181), who subsequently succeeded his father to the earldom. Matilda's marriage thus created a strong kinship alliance between two of the most powerful earldoms in twelfth-century England which was to prove especially significant during the disturbances of King Stephen's reign. Matilda may have played a central role in the capture of Lincoln Castle in December 1140, a key turning point in the conflict that set in train the series of events that led eventually to the capture of Stephen. While their husbands were besieging Lincoln Castle, Matilda and her sister-in-law Hawise, countess of Lincoln, made a friendly social visit to the wife of the castellan. Under the pretext of providing an escort for his wife's safe return to his armed camp, Earl Ranulf penetrated and captured the castle. On the subsequent approach of the king's army towards Lincoln, it is unclear whether Matilda held the castle while Ranulf attempted to rally support or whether she was captured. None the less Ranulf escaped from the castle leaving his wife and sons to face the besieging royalists. Robert, earl of Gloucester, went to the aid of Ranulf since he was worried about the safety of his daughter and grandchildren. In the subsequent battle of Lincoln on 2 February 1141 King Stephen was captured. Matilda survived her husband by forty-four years and remained unmarried throughout that period. She had dower of lands of the earldom of Chester valued at over £22 in 1185. She was occasionally involved in the public affairs of her husband's administration: for example she witnessed his charter in 1147–8 of a grant to the monks of Lenton, Nottinghamshire, which was witnessed also by, among others, the Welsh prince Cadwalader ap Gruffudd (d. 1172). Between 1141 and 1145 she received maritagium at Campden, Gloucestershire, lands that were strategically important to her husband, strengthening his position in the more southerly areas of his lordship. She also held maritagium at Great Gransden, Huntingdonshire. She was an active patron of religious houses. When married to Earl Ranulf she granted lands to Belvoir Priory, Leicestershire, between 1141 and 1147, to Bordesley Abbey, Worcestershire, in 1153, and refounded Repton Priory, Derbyshire, c.1150–1154. She witnessed her husband's charters to Garendon Abbey, Leicestershire, and to the nuns of St Mary's, Chester. In 1154–7, jointly with her son, she gave a charter to Walter, bishop of Chester, in reparation for the injuries inflicted by Earl Ranulf which had resulted in his dying excommunicate. As a widow she continued to patronize religious houses, making benefactions to her favourite priory at Repton. In 1185 she held dower in Waddington, Lincolnshire, worth £400. Matilda died on 29 July 1189. Susan M. Johns Sources Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist. · William of Malmesbury, The Historia novella, ed. and trans. K. R. Potter (1955) · K. R. Potter and R. H. C. Davis, eds., Gesta Stephani, OMT (1976) · GEC, Peerage · G. Barraclough, ed., The charters of the Anglo-Norman earls of Chester, c.1071–1237, Lancashire and Cheshire RS, 126 (1988) · J. H. Round, ed., Rotuli de dominabus et pueris et puellis de XII comitatibus (1185), PRSoc., 35 (1913) · W. Farrer, Honors and knights' fees … from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, 2 (1924) © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Susan M. Johns, ‘Matilda, countess of Chester (d. 1189)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/47213, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Matilda (d. 1189): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/472135 | |

| Name Variation | Maud of Gloucester6 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1172 | She founded Repton Priory, Derbyshire7 |

Family | Ranulph de Gernon b. c 1100, d. 16 Dec 1153 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-27.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-26.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-27.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 132A-27.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 49.

Ranulph de Gernon1

Ranulph de Gernon1

M, #1763, b. circa 1100, d. 16 December 1153

| Father* | Ranulph III le Meschin de Briquessart1,2 b. c 1070, d. 17 Jan 1128/29 or 27 Jan 1128/29 | |

| Mother* | Lucy (?)1,2 b. c 1068, d. 1141 | |

Ranulph de Gernon|b. c 1100\nd. 16 Dec 1153|p59.htm#i1763|Ranulph III le Meschin de Briquessart|b. c 1070\nd. 17 Jan 1128/29 or 27 Jan 1128/29|p102.htm#i3036|Lucy (?)|b. c 1068\nd. 1141|p59.htm#i1764|Vicomte Ranulph I. of Bayeux|b. b 1046\nd. 1129|p102.htm#i3033|Margaret d' Avranches|b. c 1054|p102.htm#i3034||||||| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1100 | Castle of Gernon, Normandy, France3,2 |

| Marriage* | circa 1141 | Principal=Maud de Caen4,2 |

| Death* | 16 December 1153 | poisoned by his wife and William Peverell3,2,5 |

| Burial* | St. Werberg's, Chester, England3,2 | |

| Title | Earl of Chester5 | |

| DNB* | Ranulf (II) [Ranulf de Gernon], fourth earl of Chester (d. 1153), magnate, was the son of Ranulf (I), third earl of Chester (d. 1129), and his wife, Lucy of Bolingbroke (d. c.1138). He had a half-brother, William de Roumare, Lucy's son from a previous marriage to Roger fitz Gerold, and a sister, Alice, who married Richard de Clare (d. 1136). Among those who witnessed his charters were Benedict ‘brother of the earl’ (presumably an illegitimate son of Ranulf (I)), Foulque de Bricquessart (probably either a nephew of Ranulf (I) or another illegitimate son), and Richard Bacun, founder c.1143 of Rocester Abbey, Staffordshire, who described Ranulf (II) as his uncle (avunculus). Succession to the earldom On his father's death in January in 1129 Ranulf (II) succeeded to his lands and titles in England and Normandy. He had evidently attained his majority, so would probably have been born during the first decade of the twelfth century. His Norman interests lay in the Bessin (the area around Bayeux) and the Avranchin (the area around Avranches), and included the hereditary vicomté of Bayeux. In England his honour as earl of Chester lay principally in the north and midlands, with the most important demesnes in north and east Cheshire (such as Eastham and Macclesfield), in Warwickshire (Coventry), Leicestershire (Barrow upon Soar), and Lincolnshire (Greetham). On or after becoming earl of Chester, Ranulf (I) had surrendered to the crown his lordship of Carlisle and most of his wife's Lincolnshire inheritance based upon Bolingbroke, none of which came later to Ranulf (II). However, about one-third of Lucy's Lincolnshire estate, largely within the soke of Belchford, had remained with Ranulf (I), was retained by Lucy until her death c.1138, and did subsequently pass to their son. The disposition of these holdings was clearly the subject of negotiation with Henry I, for among the accounts charged to Ranulf (II) in the 1130 pipe roll was a debt of £1000 left by his father ‘for the land of Earl Hugh [of Chester]’ and another debt of 500 marks for a concord over his mother's dower. Lucy herself rendered further accounts, including one of 400 marks ‘for her father's land’. Relations with Henry I and Stephen During the closing years of Henry I's reign Ranulf (II) was present at royal councils in Northampton (8 September 1131, when magnates were required to swear fealty to the Empress Matilda), Westminster (29 April 1132), and Windsor (Christmas 1132). Although favoured by geld pardons in 1130 in Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, Staffordshire, and Warwickshire, totalling £21 4s. 0d., there is no sign that he enjoyed the king's familiarity as his father had done. On the other hand, his marriage (not later than 1135) to Matilda, daughter of Robert, earl of Gloucester, associated him with the party favouring the empress's succession (after his death, his widow issued a charter referring to the empress as her aunt). Despite this, in common with nearly every other Anglo-Norman magnate, he accepted King Stephen's accession, attending the royal council at Westminster at Easter (22 March) 1136 and witnessing the Oxford charter of liberties (which signalled the earl of Gloucester's submission to Stephen) in April of that year. To all appearances Ranulf remained a loyal subject until 1140, despite his father-in-law's formal defiance of the king (May 1138) and military leadership of the Angevins in England following the empress's invasion (September 1139). An early test of Ranulf's allegiance came in February 1136, when Stephen granted Carlisle to Henry of Scotland in the first treaty of Durham. The terms were confirmed in a second treaty of 9 April 1139. Ranulf's resentment at the alienation of a lordship formerly held by his father explains, at least in part, his withdrawal from the royal council at Easter 1136 in protest at the elevated position enjoyed there by Henry of Scotland, and his attempt in 1140 to capture Henry and his wife on their return from Stephen's court. However, the significance of Carlisle in motivating Ranulf's behaviour should not be exaggerated. It lay far from his main territorial interests, and he seems to have played no part in the military campaigns against the Scots which reached a climax with their defeat at the battle of the Standard in August 1138. The earl of Chester's principal ambitions were focused instead on the north midlands, especially in Lincolnshire where his mother's inheritance lay. Having antagonized the king through his bid to capture Henry of Scotland, Ranulf compounded his offence later in 1140 by contriving the seizure of the royal castle at Lincoln. He arrived unarmed with three knights, ostensibly to collect his wife, and the wife of William de Roumare, who had been paying a social visit. On being allowed in, they seized weapons, expelled the royal garrison, and admitted Roumare and his men. The king's response was to visit Lincolnshire, but instead of taking reprisals against the half-brothers he treated them with favour: William of Malmesbury said that he ‘added to [their] honours’ (Malmesbury, 80–81), the Gesta Stephani that he peaceably renewed a pact with Ranulf while intending to watch whether the promises were kept. Stephen left for London before Christmas, but made a surprise return during the festival to lay siege to Lincoln Castle. Ranulf managed to escape, obtained the armed assistance of his father-in-law, Robert, earl of Gloucester, and other Angevin adherents, raised soldiers from Cheshire and Wales, and marched back to Lincoln, where his wife and half-brother were continuing to resist the siege. At the battle of Lincoln on 2 February 1141 both Stephen and Ranulf fought on foot. The king was captured, and the earl followed up his victory with sack and slaughter in the city itself. Ranulf and the Empress Matilda Although he played a leading role in the king's downfall, an event which looked set to bring the Empress Matilda to power, it seems clear that Ranulf fought primarily not on behalf of a contender for the throne, but for himself and his family. According to William of Malmesbury ‘he seemed ambivalent in his loyalty’ (Malmesbury, 82–3), and promised fealty to the empress only on condition that the earl of Gloucester would help him relieve Lincoln Castle. The speeches before the battle, put into the mouths of the protagonists by Henry of Huntingdon, have Ranulf perceiving the conflict in personal terms, to avenge the wrong done to himself, in contrast to Robert of Gloucester for whom the crown was at stake. Ranulf's ambivalence over the succession dispute, and consequent distrust by both parties, was repeatedly illustrated during the years which followed. He is not known to have attested any of the empress's charters after Stephen's accession. At the siege of Winchester in September 1141 he initially joined the queen's army, only to encounter such suspicion and hostility that he switched to the empress's camp; here, according to William of Malmesbury, his arrival was ‘late and ineffective’ (ibid., 102–03). His Norman castle at Bricquessart fell to the Angevins in 1142, and the castle he had taken at Lincoln withstood a siege by Stephen two years later. Although he subsequently met Stephen at Stamford (probably early in 1146, when the royalist cause was gaining ground) and apparently renewed his fealty to the king, even this reconciliation did not persist. He duly helped Stephen to capture Bedford town and besiege Wallingford Castle, but the king and the royalist magnates remained deeply suspicious of his failure to restore revenues from royal lands and castles he had seized, and thought he should give hostages to secure his good faith. He was again with the king at Northampton on 29 August 1146, but here his request that Stephen help him to campaign against the Welsh was seen as an attempted entrapment, and his refusal to give hostages or restore royal property led to his sudden arrest and imprisonment. He was released after agreeing to Stephen's terms and taking an oath not to resist the king in future, whereupon he set about trying to recover by force what he had been obliged to surrender. Subsequent campaigns led to armed confrontations with Stephen's son Eustace, and on at least two occasions, near Coventry (probably early in 1147) and Lincoln (1149), with the king himself. Extension of Ranulf's basis of power In the years following the battle of Lincoln Ranulf was also involved in a series of conflicts and negotiations with northern and midlands barons, including Alan, earl of Richmond, William, count of Aumale, Robert Marmion, and Gilbert de Gant, who was captured in the battle and forced to marry the earl's niece Rohese de Clare. His consistent purpose was to strengthen his authority from the west coast to the east, and to this end he kept a house in Lincoln with separate household officials, refined his honorial administration especially for financial affairs, and employed a scribe as accomplished as those in royal service. A charter issued by Stephen, undated but probably attributable to the brief reconciliation of 1146, demonstrates the extent of his ambitions. He was granted royal manors in Warwickshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, and Lincolnshire, the towns of Newcastle under Lyme, and Derby, land in Grimsby, and the soke of Grantham, plus the honours of William d'Aubigny Brito (Belvoir), Roger de Bully (Tickhill), and Roger de Poitou (Lancaster, although that which lay north of the Ribble was under Scottish control). He was also confirmed in his tenure of Lincoln Castle, including the right to retain ‘Lucy's tower’, a reference which hints at the hereditary claims which had underlain his seizure of the castle. Much of this may already have been encroached upon by Ranulf, and much was presumably surrendered as the price of his release following his arrest at Northampton: Lincoln, for example, was in Stephen's hands by Christmas 1146, and, despite attacks on the castle in 1147 and 1149, Ranulf failed to regain it. The death of Robert, earl of Gloucester, in October 1147, followed by the retirement of the Empress Matilda to Normandy early in 1148, brought a change in the political context, and with it Ranulf's closer association with the Angevin party. There is charter evidence of a gathering at Chester of the king's principal baronial opponents, such as Roger, earl of Hereford, and Gilbert fitz Richard, earl of Hertford, some time in 1147 or 1148, and also of a visit by Ranulf during this period to the Angevin headquarters at Bristol. Most significantly, when the future Henry II (then aged sixteen) was knighted by David, king of Scots, at Carlisle on Whitsunday (22 May) 1149, Ranulf was in attendance. He did homage to King David, who granted him the honour of Lancaster (including lands north of the Ribble) in exchange for a renunciation of claims to Carlisle; it was also agreed that Ranulf's son would marry one of the daughters of Henry of Scotland. Ranulf almost certainly did homage to the future Henry II on this occasion also, for he addressed him as ‘his lord’ in a charter of March 1150 at the latest. The immediate consequences of this meeting were slight: a plan to launch a combined assault on York was thwarted by Stephen's arrival, Ranulf was blamed by the king of Scots for failing to deliver his promises, and the proposed marriage never took place. But the earl of Chester had clearly made a firmer commitment to the Angevin cause than at any previous time in the civil war, and he was prepared to be a witness to Henry's charters both on this visit and on his return to England in 1153. Even so, Ranulf continued to put his own interests first. Some time between 1149 and 1153 he made a formal agreement with Robert, earl of Leicester, whereby each pledged to bring only twenty knights if obliged by his liege lord to fight against the other, and generally to limit the impact of the war upon their estates. In the event, both earls joined the Angevin campaign in 1153, but Ranulf still struck a hard bargain, securing from Henry (not later than April) a charter issued at Devizes attested by ten men ‘on the part of earl Ranulf’ to complement the eleven other witnesses. This made lavish grants in the north midlands, many repeating those given by Stephen probably in 1146 but also including the estates of several royalist barons which the earl was effectively being invited to seize. Among these were the holdings of William Peverel of Nottingham, who was widely believed to have been responsible for Ranulf's death, and who in 1155 was disinherited for the crime. As a marcher earl, Ranulf had to cope with a resurgence of Welsh aggression. In 1136 or 1137 he led a disastrous expedition into Wales from which he was one of the few to escape alive. In 1146 raids into Tegeingl east of the River Clwyd by Owain, king of Gwynedd, prompted Ranulf's appeal to Stephen for military assistance; within days of the earl's arrest, the Welsh were invading Cheshire, and reached Nantwich before being driven out by his seneschal Robert de Montalt on 3 September. Four years later, in alliance with Madog ap Maredudd, king of Powys, he prepared an attack on Owain Gwynedd, but the enterprise collapsed after defeat at Coleshill. As this episode demonstrates, Ranulf fully appreciated the value of co-operation as well as confrontation with the Welsh princes. Cadwaladr, brother of Owain Gwynedd, was a son-in-law of Ranulf's sister Alice. He accompanied Ranulf to the battle of Lincoln, where Welsh forces figured prominently, and was welcomed to the earl's court in the late 1140s and early 1150s, when he witnessed charters as ‘king of Wales’ in defiance of his brother. A Welsh prince referred to by Orderic Vitalis as Maredudd—probably Cadwaladr's brother-in-law Madog ap Maredudd of Powys, but possibly Cadwaladr's son Maredudd—was also with Ranulf at the battle of Lincoln. Despite Ranulf's interests in Normandy, none of his charters is known to have been issued there, and the focus of his attention was clearly upon the English side of the channel. He certainly lost his Norman estates during the civil war: Bricquessart fell to the Angevins in 1142, and the lands Ranulf held from the bishop and cathedral of Bayeux featured in a charter of Robert, earl of Gloucester, in September 1146. At Devizes in 1153 the future Henry II duly restored Ranulf's ‘Norman inheritance’, interpreting this liberally to include Breuil, the castle of Vire, and other holdings once associated with his family, together with comital status and extensive lordship in the Avranchin. As with Henry's other promises to Ranulf in 1153, however, these did not survive the earl's death, and his son succeeded, in Normandy as in England, substantially to the position enjoyed at Stephen's accession. Philanthropy, death, and reputation Ranulf founded four religious houses, an abbey for Savignac monks at Basingwerk, Flintshire, in 1131, priories for Benedictine monks and nuns at Minting, Lincolnshire, and Chester respectively (both at uncertain dates), and a priory for Augustinian canons at Trentham, Staffordshire. The last foundation, made on his deathbed in 1153, was probably the restoration of a house originally established by Hugh d'Avranches. At the end of his life he also compensated Lincoln Cathedral and the abbeys at Burton and Chester for the evils inflicted upon them, and soon after his death his widow and son made a grant to Walter, bishop of Chester, specifically for his absolution. The author of the Gesta Stephani suggests that he was excommunicated some time in the late 1140s, but, if so, reconciliation with the church seems apparent from a gift he made to Bordesley Abbey, Worcestershire, between 1149 and 1153, at the instigation, and in the presence, of Bishop Walter, and also from the fact that, according to later tradition, he was buried next to his father in Chester Abbey. Ranulf died on 17 December 1153 at Gresley, Derbyshire. According to the Gesta Stephani, the earl was given poisoned wine while a guest at the house of William Peverel. In this version, he ‘just recovered, only because he had not drunk much’, but in any event he did not survive for long. Ranulf's wife, Matilda, who in 1172 founded Repton Priory, Derbyshire, died on 29 July 1189. Their son Hugh of Cyfeiliog, born in 1147, succeeded him as earl of Chester, taking seisin of the lands in 1162. Most contemporary verdicts upon Ranulf were unfavourable. Although Orderic Vitalis acknowledged his resourcefulness and daring, the Gesta Stephani criticized ‘the cunning devices of his accustomed bad faith’ (Gesta Stephani, 192–3), and Henry of Huntingdon, through a speech supposedly by the royalist spokesman at the battle of Lincoln, called him ‘a man of reckless daring, ready for conspiracy … panting for the impossible’, prone to defeat or, at best, to Pyrrhic victories (Historia Anglorum, 734–5). Clearly, his strategy during the civil war was to take every opportunity to enhance his territorial position, especially in the north midlands, and such commitments as he made, either to the king or to the Angevins, were calculated to that end. Other magnates followed similar policies, but Ranulf (II) was exceptionally ruthless in pursuit of his ambitions, and accordingly he was hated by many and trusted by none. Graeme White Sources G. Barraclough, ed., The charters of the Anglo-Norman earls of Chester, c.1071–1237, Lancashire and Cheshire RS, 126 (1988) · Reg. RAN, vols. 2–3 · K. R. Potter and R. H. C. Davis, eds., Gesta Stephani, OMT (1976) · Henry, archdeacon of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum, ed. D. E. Greenway, OMT (1996) · William of Malmesbury, Historia novella: the contemporary history, ed. E. King, trans. K. R. Potter, OMT (1998) · Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., vol. 6 · R. C. Christie, ed. and trans., Annales Cestrienses, or, Chronicle of the abbey of S. Werburg at Chester, Lancashire and Cheshire RS, 14 (1887) · Pipe rolls, 31 Henry I · M. V. Taylor, ‘Some obits of abbots and founders of St Werburgh's Abbey, Chester’, Liber Luciani de laude Cestrie, ed. M. V. Taylor, Lancashire and Cheshire RS, 64 (1912) · Dugdale, Monasticon, new edn, vols. 3, 6 · Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, 71 (1991) [G. Barraclough issue, The earldom of Chester and its charters, ed. A. T. Thacker] · P. Dalton, ‘In neutro latere: the armed neutrality of Ranulf II, earl of Chester in King Stephen's reign’, Anglo-Norman Studies, 14 (1991), 39–59 · F. M. Stenton, The first century of English feudalism, 1066–1166, 2nd edn (1961) © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Graeme White, ‘Ranulf (II) , fourth earl of Chester (d. 1153)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/23128, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Ranulf (II) (d. 1153): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/231286 | |

| Name Variation | Radnulf de Gernon2 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1 September 1131 | Northampton, He witnessed the Charter to Salisbury granted by Henry I5 |

| Event-Misc | 1136 | He was a witness to the Charter of Liberties5 |

| Battle-Lincoln* | 2 February 1140/41 | Principal=Stephen of Blois, Stephen=John d' Eu, Stephen=Hugh Bigod, Ranulph=Robert de Caen, Stephen=William Peverell, Stephen=Sir William de Warenne, Stephen=Waleran de Beaumont7 |

| Event-Misc | 29 August 1146 | He was seized at court by King Stephen5 |

| Title* | Normandy, France, Vicomte d'Avranches3 |

Family | Maud de Caen b. c 1120, d. 29 Jul 1189 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-27.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 132A-27.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-27.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 49.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 28.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 50.

Lucy (?)1

F, #1764, b. circa 1068, d. 1141

| Birth* | circa 1068 | 2 |

| Marriage* | Groom=Ives Taillebois3 | |

| Marriage* | Groom=Roger FitzGerold3,2 | |

| Marriage* | circa 1098 | Groom=Ranulph III le Meschin de Briquessart3,4 |

| Death* | 1141 | 2 |

| Living* | 1130 | 3 |

Family 1 | Roger FitzGerold d. 15 Jul | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | Ranulph III le Meschin de Briquessart b. c 1070, d. 17 Jan 1128/29 or 27 Jan 1128/29 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 15 May 2005 |

Robert de Caen1

M, #1765, b. circa 1090, d. 31 October 1147

| Father* | Henry I Beauclerc2,3 b. 1068, d. 1 Dec 1135 | |

| Mother* | Nesta verch Rhys3 b. c 1073 | |

Robert de Caen|b. c 1090\nd. 31 Oct 1147|p59.htm#i1765|Henry I Beauclerc|b. 1068\nd. 1 Dec 1135|p55.htm#i1629|Nesta verch Rhys|b. c 1073|p117.htm#i3498|William I. of Normandy "the Conqueror"|b. 1027\nd. 9 Sep 1087|p59.htm#i1768|Maud of Flanders|b. 1032\nd. 3 Nov 1083|p59.htm#i1769|Rhys ap Tewdr Mawr|d. Apr 1093|p136.htm#i4068|Gwladus fil Rhiwallon||p136.htm#i4069| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1090 | 2 |

| Birth | 1100 | Caen, France3 |

| Marriage* | 1119 | Principal=Maud FitzRobert4,3 |

| Death* | 31 October 1147 | Bristol, Gloucestershire, England, of fever2,3,5 |

| Burial* | Priory of St. James, Bristol5 | |

| Title | 1st Earl of Gloucester6 | |