Nesta FitzOsbern1

F, #2701, b. circa 1079

| Father* | Osborn FitzRichard2,3,4 d. a 1086 | |

| Mother* | Nesta of North Wales2,3,4 b. c 1057 | |

Nesta FitzOsbern|b. c 1079|p91.htm#i2701|Osborn FitzRichard|d. a 1086|p91.htm#i2710|Nesta of North Wales|b. c 1057|p91.htm#i2709|Richard FitzScrob|d. 1067|p91.htm#i2711|Anonyma de Essex||p160.htm#i4773|Gruffydd ap Llywelyn|b. c 1011\nd. 5 Aug 1063|p91.htm#i2712|Aldgyth of Mercia|d. a 1086|p91.htm#i2713| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Bernard de Neufmarché5,6,3 | |

| Birth* | circa 1079 | Herefordshire, England3 |

| Name Variation | Nesta fil Trahern3 |

Family | Bernard de Neufmarché b. c 1050, d. 1093 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 29 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 176.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 177-2.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S232] Don Charles Stone, Ancient and Medieval Descents, 21-4.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 177-3.

- [S232] Don Charles Stone, Ancient and Medieval Descents, 21-5.

Geoffrey (?)1

M, #2702

| Father* | Thurcytel (?)1,2 | |

Geoffrey (?)||p91.htm#i2702|Thurcytel (?)||p91.htm#i2703||||Anchetil de Harcourt|d. a 1027|p199.htm#i5960|Eva d. Boessey la Chastel||p198.htm#i5918||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Ada FitzRichard1,2 | |

| Name Variation | Geoffrey de Neufmarch2 |

Family | Ada FitzRichard | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Thurcytel (?)1

M, #2703

| Father* | Anchetil de Harcourt2 d. a 1027 | |

| Mother* | Eva de Boessey la Chastel2 | |

Thurcytel (?)||p91.htm#i2703|Anchetil de Harcourt|d. a 1027|p199.htm#i5960|Eva de Boessey la Chastel||p198.htm#i5918|Turchetil de Harcourt|b. c 960\nd. a 1027|p198.htm#i5919|Anceline d. Montfort-sur-Risle||p198.htm#i5920||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | 2 | |

| Name Variation | Thurcytal Neufmarche2 |

Family | ||

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Ada FitzRichard1

F, #2704

| Father* | Richard FitzGulbert1,2 | |

| Mother* | Ada Hugleville2 | |

Ada FitzRichard||p91.htm#i2704|Richard FitzGulbert||p91.htm#i2705|Ada Hugleville||p198.htm#i5922|Gulbert St. Valerie|d. a 1011|p91.htm#i2706|Papia (?)||p91.htm#i2707|Herluin d. Hugleville||p198.htm#i5923|||| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Geoffrey (?)1,2 | |

| Name Variation | Ada de Hugleville2 |

Family | Geoffrey (?) | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Richard FitzGulbert1

M, #2705

| Father* | Gulbert St. Valerie1,2 d. a 1011 | |

| Mother* | Papia (?)1,2 | |

Richard FitzGulbert||p91.htm#i2705|Gulbert St. Valerie|d. a 1011|p91.htm#i2706|Papia (?)||p91.htm#i2707|Bernard I. de Gamaches||p147.htm#i4383|Emma de St. Valerie||p147.htm#i4384|Richard I. of Normandy "the Fearless"|b. 933\nd. 20 Nov 996|p91.htm#i2708|Papie (?)||p358.htm#i10735| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Ada Hugleville2 | |

| Name Variation | Richard Hugleville2 | |

| Living* | between 1025 and 1053 | Normandy, France1 |

| Title* | Seigneur of Hugleville and Auffay1 |

Family | Ada Hugleville | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Gulbert St. Valerie1

M, #2706, d. after 1011

| Father* | Bernard I de Gamaches2 | |

| Mother* | Emma de St. Valerie2 | |

Gulbert St. Valerie|d. a 1011|p91.htm#i2706|Bernard I de Gamaches||p147.htm#i4383|Emma de St. Valerie||p147.htm#i4384|William d. Gamaches||p147.htm#i4386|Alice o. P. Gamaches||p147.htm#i4387|Renaud I. (?)||p147.htm#i4388|||| | ||

| Birth* | of Saint-Valery-en-Caux, France2 | |

| Marriage* | Principal=Papia (?)1,2 | |

| Death* | after 1011 | 2 |

| Name Variation | Gilbert de St. Valerie2 | |

| Living* | 1011 | 1 |

Family | Papia (?) | |

| Children | ||

| Last Edited | 30 May 2005 |

Papia (?)1

F, #2707

| Father* | Richard I of Normandy "the Fearless" b. 933, d. 20 Nov 996; illegitimate1 | |

| Mother* | Papie (?)2 | |

| Father | Richard II of Normandy "the Good"2 b. c 958, d. 28 Aug 1026 | |

Papia (?)||p91.htm#i2707|Richard I of Normandy "the Fearless"|b. 933\nd. 20 Nov 996|p91.htm#i2708|Papie (?)||p358.htm#i10735|William of Normandy "Longsword"|b. c 891\nd. 17 Dec 942|p147.htm#i4389|Espriota d. St. Liz|b. c 911|p147.htm#i4390||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Gulbert St. Valerie1,2 | |

| Name Variation | Papia of Normandy2 |

Family | Gulbert St. Valerie d. a 1011 | |

| Children | ||

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Richard I of Normandy "the Fearless"1

Richard I of Normandy "the Fearless"1

M, #2708, b. 933, d. 20 November 996

| Father* | William of Normandy "Longsword"2,3 b. c 891, d. 17 Dec 942 | |

| Mother* | Espriota de St. Liz2,3 b. c 911 | |

Richard I of Normandy "the Fearless"|b. 933\nd. 20 Nov 996|p91.htm#i2708|William of Normandy "Longsword"|b. c 891\nd. 17 Dec 942|p147.htm#i4389|Espriota de St. Liz|b. c 911|p147.htm#i4390|Hrólfr Rögnvaldsson|b. 846\nd. c 927|p149.htm#i4449|Poppa de Valois||p149.htm#i4450|Hubert (?)||p149.htm#i4451|||| | ||

| Birth* | 933 | Fecamp, France2,4 |

| Marriage* | 960 | (his Christian wife), Bride=Emma of Burgundy2,4 |

| Marriage* | after 968 | "Danish" wife, c 945, but married her after death of Emma to legitimize her children, born prior to marriage to Emma., Bride=Gunnora (?)2,4 |

| Mistress* | Principal=Papia (?)2 | |

| Death* | 20 November 996 | Fecamp, France2,4 |

| HTML* | The Little Duke The Normans The Norman World Wikipedia article |

Family 1 | Papie (?) | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | ||

| Children |

| |

Family 3 | Gunnora (?) d. 1031 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 4 | Emma of Burgundy b. c 943, d. 19 Mar 968 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 2 Jul 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 177-3.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 121E-19.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 121E-20.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 51.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 182.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 39-22.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 68.

Nesta of North Wales1

F, #2709, b. circa 1057

| Father* | Gruffydd ap Llywelyn2,3,4 b. c 1011, d. 5 Aug 1063 | |

| Mother* | Aldgyth of Mercia2,3 d. a 1086 | |

Nesta of North Wales|b. c 1057|p91.htm#i2709|Gruffydd ap Llywelyn|b. c 1011\nd. 5 Aug 1063|p91.htm#i2712|Aldgyth of Mercia|d. a 1086|p91.htm#i2713|Llewelyn ap Seisyll|b. c 980\nd. 1023|p160.htm#i4774|Angharad ferch Maredudd|b. c 982|p160.htm#i4771|Ælfgar I. Earl of Mercia|b. c 1030\nd. 1062|p156.htm#i4676|Ælgifu of England|b. c 997|p80.htm#i2388| | ||

| Of | Rhuddlan, Flintshire, Wales3 | |

| Marriage* | Principal=Trahearn (?)3 | |

| Birth* | circa 1057 | 1,5 |

| Marriage* | Principal=Osborn FitzRichard1,3,5 | |

| Name Variation | Nesta verch Gruffydd3 |

Family 1 | Osborn FitzRichard d. a 1086 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Trahearn (?) b. c 1044, d. 1129 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 12 Jul 2005 |

Osborn FitzRichard1

M, #2710, d. after 1086

| Father* | Richard FitzScrob1,2 d. 1067 | |

| Mother* | Anonyma de Essex2 | |

Osborn FitzRichard|d. a 1086|p91.htm#i2710|Richard FitzScrob|d. 1067|p91.htm#i2711|Anonyma de Essex||p160.htm#i4773|Cynfyn ap Gwerystan||p159.htm#i4770|Angharad ferch Maredudd|b. c 982|p160.htm#i4771|Robert d. E. (?)|b. 1007\nd. 1071|p306.htm#i9175|||| | ||

| Birth* | of Arwystle2 | |

| Marriage* | Principal=Nesta of North Wales1,2,3 | |

| Death* | after 1086 | 2 |

| Name Variation | Osbert1 | |

| Name Variation | Osbern FitzRichard2 | |

| Occupation* | 1060 | Herefordshire, England, Sheriff of Herefordshire1,3 |

| Residence* | Richard's Castle, Herefordshire, England1 | |

| Living* | 1100 | 1,3 |

Family | Nesta of North Wales b. c 1057 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Richard FitzScrob1

M, #2711, d. 1067

| Father* | Cynfyn ap Gwerystan2 | |

| Mother* | Angharad ferch Maredudd2 b. c 982 | |

Richard FitzScrob|d. 1067|p91.htm#i2711|Cynfyn ap Gwerystan||p159.htm#i4770|Angharad ferch Maredudd|b. c 982|p160.htm#i4771|Gwerystan ap Gwaithfoed|b. c 950|p160.htm#i4784|Nest ferch Cadell ap Brochwel|b. c 954|p244.htm#i7293|Maredudd ap Owain ap Hywel Dda|b. c 938\nd. 999|p160.htm#i4785|Asritha (?)||p160.htm#i4786| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Anonyma de Essex2 | |

| Death* | 1067 | 1 |

| Death | circa 1080 | 2 |

| Residence* | Richard's Castle, Herefordshire, England1 |

Family | Anonyma de Essex | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Oct 2003 |

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn1

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn1

M, #2712, b. circa 1011, d. 5 August 1063

| Father* | Llewelyn ap Seisyll2 b. c 980, d. 1023 | |

| Mother* | Angharad ferch Maredudd2 b. c 982 | |

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn|b. c 1011\nd. 5 Aug 1063|p91.htm#i2712|Llewelyn ap Seisyll|b. c 980\nd. 1023|p160.htm#i4774|Angharad ferch Maredudd|b. c 982|p160.htm#i4771|Seissyllt a. E. (?)||p171.htm#i5121|Trawst v. E. (?)||p171.htm#i5122|Maredudd ap Owain ap Hywel Dda|b. c 938\nd. 999|p160.htm#i4785|Asritha (?)||p160.htm#i4786| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1011 | of Rhuddlan, Flintshire, Wales2 |

| Marriage* | circa 1057 | 1st=Aldgyth of Mercia1,2,3 |

| Death* | 5 August 1063 | (slain)1,2,3 |

| Name Variation | Griffith ap Llewelyn (?)2 | |

| HTML* | King of Wales |

Family | Aldgyth of Mercia d. a 1086 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 12 Jul 2005 |

Aldgyth of Mercia1

F, #2713, d. after 1086

| Father* | Ælfgar III Earl of Mercia2,3,4 b. c 1030, d. 1062 | |

| Mother* | Ælgifu of England2,4 b. c 997 | |

Aldgyth of Mercia|d. a 1086|p91.htm#i2713|Ælfgar III Earl of Mercia|b. c 1030\nd. 1062|p156.htm#i4676|Ælgifu of England|b. c 997|p80.htm#i2388|Leofric I. Earl of Mercia|b. 975\nd. 31 Aug 1057|p156.htm#i4678|Godgifu (?)|b. c 1010\nd. 10 Sep 1067|p156.htm#i4679|Æthelred I. of England "the Unready"|b. 968\nd. 23 Apr 1016|p55.htm#i1636|Ælfgifu (?)|d. bt 1002 - 1003|p55.htm#i1637| | ||

| Marriage* | circa 1057 | Groom=Gruffydd ap Llywelyn1,2,5 |

| Marriage* | circa 1064 | Groom=Harold II Godwinson2,5 |

| Death* | after 1086 | 2,3 |

| Name Variation | Edith (?)1 | |

| Name Variation | Agatha fil Algar (?)2 |

Family 1 | Harold II Godwinson b. 1022, d. 14 Oct 1066 | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | Gruffydd ap Llywelyn b. c 1011, d. 5 Aug 1063 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 12 Jul 2005 |

Sir John le Strange of Blackmere1,2

M, #2714, b. 26 January 1306/7, d. 21 July 1349

|

| Father* | Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere1 b. c 1267, d. 23 Jan 1324/25 | |

| Mother* | Eleanor Gifford b. 1275, d. b 1325 | |

Sir John le Strange of Blackmere|b. 26 Jan 1306/7\nd. 21 Jul 1349|p91.htm#i2714|Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere|b. c 1267\nd. 23 Jan 1324/25|p91.htm#i2715|Eleanor Gifford|b. 1275\nd. b 1325|p99.htm#i2952|Sir Robert le Strange|d. b 10 Sep 1276|p99.htm#i2963|Eleanor de Whitchurch|d. c 1304|p99.htm#i2966|Sir John Gifford|b. c 1232\nd. 28 May 1299|p99.htm#i2955|Maud de Clifford|d. bt 1282 - 1285|p99.htm#i2956| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | 26 January 1306/7 | 3 |

| Birth | circa 1306/7 | (aged 18 on 23 Jan 1324/5)2 |

| Marriage* | before 1328 | 1st=Ankaret le Boteler3 |

| Death* | 21 July 1349 | 4,3 |

| Title* | 2nd Lord Strange of Blackmere3 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1 August 1325 | John, son of Fulk le Strange, is made Custos of his lands at £400 rent2 |

| Event-Misc | 26 February 1326/27 | proved his age and did homage5 |

| Summoned* | from 23 October 1330 to 20 April 1344 | Parliament by writs directed Johanni Lestraunge3 |

| Event-Misc | 1346 | He accompanied the King to Normandy and was present at the seige of Crecy and Calais3 |

| Summoned | between 1 January 1348/49 and 10 March 1348/49 | Parliament by writs directed Johanni Lestraunge de Blakemere3 |

Family | Ankaret le Boteler d. 8 Oct 1361 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Apr 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8-32.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 295.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Blackmere 8.

- [S230] Adrian Channing, Le Strange in "Origin of Strange," listserve message 11 Apr 2003.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 232.

Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere1

Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere1

M, #2715, b. circa 1267, d. 23 January 1324/25

|

| Father* | Sir Robert le Strange2 d. b 10 Sep 1276 | |

| Mother* | Eleanor de Whitchurch2 d. c 1304 | |

Sir Fulk le Strange of Blackmere|b. c 1267\nd. 23 Jan 1324/25|p91.htm#i2715|Sir Robert le Strange|d. b 10 Sep 1276|p99.htm#i2963|Eleanor de Whitchurch|d. c 1304|p99.htm#i2966|Sir John le Strange|b. s 1190|p99.htm#i2964|Lucy de Tregoz|b. c 1202\nd. a 1294|p99.htm#i2965|William de Blauminster||p474.htm#i14218|||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1267 | 2,3 |

| Marriage* | before 1307 | Principal=Eleanor Gifford2,3,4 |

| Death* | 23 January 1324/25 | shortly before 23 Jan 1324/25, holding Manors of Chalghton (Chawton) as 1 Fee in Hants., Wrocworthyn and Whitchurch, Salop, and in right of his w. Eleanor, dec., Corfham Castle as 1 Fee in Salop, and 1/3 of Thornhagh Manor, Notts., and left s. h. John, 18. He and 2 others held 15 Fees at Gresham, howton, Aylmerton, and elsewhere in Norf., late of Aymer, E. of Pembroke.2,5 |

| Title* | Seneschal of Aquitaine, Lord Stange of Blackmere6 | |

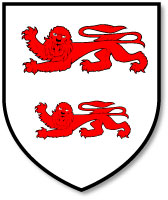

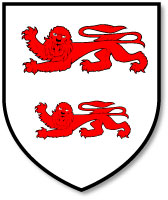

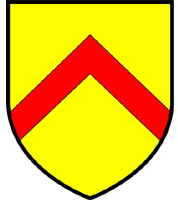

| Arms* | De argent a ii lions passanz de goules (Parl., Stepney).3 | |

| Event-Misc* | 13 September 1276 | S. of Rob. le Strange, who before going to the Holy Land enfeoffed him of Sutton Madok Manor, Salop., Principal=Sir Robert le Strange3 |

| Event-Misc* | 18 June 1289 | Aged 21-2, bro. h. of Jn. le Strange, s. of Rob. le Strange by Eleanor, d. coh. of Wm. de Blauminster, Principal=John le Strange3 |

| Event-Misc | 16 July 1289 | He should have his brother's lands on the condition of doing homage to the King when Edward I was next in England7 |

| Event-Misc* | 14 July 1294 | Going to Gascony for the King, he has Lic. to cut wood val. £40 in his wood of Chalghton in Porcestre Forest3 |

| Feudal* | 3 March 1297 | Chauton Manor, Hants., late of Hamo le Strange, and for his good service in Gascony has quittance of £24 owing by Hamo as Sheriff of Hants.3 |

| Summoned* | 7 July 1297 | serve over seas.3 |

| Summoned | 25 May 1298 | serve against the Scots3 |

| Protection* | 16 November 1299 | to Scotland for the King with Wm. le Latimer, Principal=Sir William de Latimer3 |

| Event-Misc | 14 January 1300 | He is to summon Kts. and others of Cheshire to the King at Carlisle3 |

| Event-Misc | 1301 | Sealed letter to the Pope as lord of Corfham3 |

| Event-Misc* | 22 October 1305 | Fulk le Strange is Custos of the lands of Richard FitzAlan in Salop and Wales, Principal=Sir Richard FitzAlan8 |

| Event-Misc* | 20 December 1307 | Dispensation to Fulk le Strange, lord of Witechirche, and Margaret (als. Eleanor), d. of late Jn. Giffard, lord of Corsham, to continue married and their issue legitimate, though related in 4th degree, Principal=Eleanor Gifford3 |

| Summoned | between 4 March 1309 and 26 December 1323 | Parliament9 |

| Event-Misc | 4 May 1309 | Appointed Commissioner in Cheshire3 |

| Event-Misc | 31 December 1312 | He complains that being an adherent of Thos., E. of Lancaster, though having safe conduct, his goods were seized to the King3 |

| Event-Misc | 16 October 1313 | He was pardoned re Gaveston3 |

| Event-Misc | 6 November 1313 | Granted amnesty re siege of La Pole Castle and deeds of arms in Powys5 |

| Feudal | 5 March 1318 | Blaunchminster (Whitchurch), Rocardyne, Corsham als. Corfham, Longenolr', and Sutton in Salop, Chalston, Clanfield, Blendworth, and Catherington, Hants5 |

| Event-Misc | 22 October 1318 | Pardoned as an adherent of Thos. of Lancaster5 |

| Event-Misc | 19 January 1321 | He is a commissioner to make peace with Robert the Bruce.5 |

| Event-Misc | 1322 | He was appointed Seneschal of Aquitaine7 |

| Summoned | 14 February 1322 | march against the rebels5 |

| Protection* | 6 May 1322 | to Gascony for the King5 |

| Event-Misc | 14 July 1322 | Has lic. to crenellate his dwelling place of Whitecherche5 |

| Event-Misc | 2 June 1323 | He was Senschal of Gascony5 |

Family | Eleanor Gifford b. 1275, d. b 1325 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 27 Aug 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8-32.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-30.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 294.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 123.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 295.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Blackmere 8.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 234.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 31.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 231.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 29A-31.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 232.

Mary FitzAlan1

F, #2716, d. 1361

| Father-Oth* | Sir Edmund FitzAlan7 b. 1 May 1285, d. 17 Nov 1326 | |

| Mother-Oth* | Alice de Warrenne7 b. bt 1285 - 1287, d. b 23 May 1338 | |

| Father | Sir Richard "Copped Hat" FitzAlan2,3,4,5 b. c 1313, d. 24 Jan 1375/76 | |

| Mother | Isabel le Despenser2,3,4,6 b. 1312 | |

Mary FitzAlan|d. 1361|p91.htm#i2716|Sir Edmund FitzAlan|b. 1 May 1285\nd. 17 Nov 1326|p69.htm#i2054|Alice de Warrenne|b. bt 1285 - 1287\nd. b 23 May 1338|p69.htm#i2053|Sir Richard FitzAlan|b. 3 Feb 1266/67\nd. 9 Mar 1301/2|p100.htm#i2985|Alasia de Saluzzo|b. c 1271\nd. 25 Sep 1292|p100.htm#i2986|Sir William de Warrenne|b. 15 Jan 1256\nd. 15 Dec 1285|p69.htm#i2052|Joan de Vere|b. c 1264\nd. 21 Nov 1293|p69.htm#i2051| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | before 1354 | Principal=Sir John le Strange8,9,10,5,11 |

| Death-alt* | 1361 | 1 |

| Death | 29 August 1363 | 6 |

| Death | 29 August 1396 | 3,9 |

| Name Variation | Isabel FitzAlan8 |

Family | Sir John le Strange b. 19 Apr 1332, d. 12 May 1361 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Dec 2004 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 36.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8-31.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-6.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 8.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cergeaux 10.

- [S213] Chris Philips,Corrections to Complete Peerage, online http://www.medievalgenealogy.org.uk/cp/

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8-32.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-7.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p.36.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Blackmere 9.

- [S230] Adrian Channing, Le Strange in "Origin of Strange," listserve message 11 Apr 2003.

Sir William la Zouche Mortimer1

M, #2717, b. after 1274, d. 28 February 1336/37

| Birth* | after 1274 | 2 |

| Marriage* | circa 26 October 1316 | 3rd=Alice de Tony2 |

| Marriage* | circa February 1329 | 2nd=Eleanor de Clare1,3,4,5 |

| Death* | 28 February 1336/37 | 4,5 |

| Burial* | Tewkesbury Abbey, Gloucestershire, England5 | |

| Criminal* | 5 February 1328/29 | ordered arrested, Principal=Eleanor de Clare2 |

Family | Eleanor de Clare b. Oct 1292, d. 30 Jun 1337 | |

| Children | ||

| Last Edited | 30 Oct 2004 |

Sir Richard Talbot M.P.1

M, #2718, b. circa 1305, d. 23 October 1356

| Father* | Sir Gilbert Talbot b. 18 Oct 1276, d. 24 Feb 1346; son and heir2,3 | |

| Mother* | Anne le Boteler4 | |

Sir Richard Talbot M.P.|b. c 1305\nd. 23 Oct 1356|p91.htm#i2718|Sir Gilbert Talbot|b. 18 Oct 1276\nd. 24 Feb 1346|p365.htm#i10933|Anne le Boteler||p365.htm#i10934|Richard Talbot|b. c 1250\nd. b 3 Sep 1306|p365.htm#i10936|Sarah de Beauchamp|d. a Jul 1317|p231.htm#i6905|Sir William le Boteler of Wem|d. b 11 Dec 1283|p365.htm#i10935|Ankaret verch Griffith|b. c 1248\nd. a 22 Jun 1308|p478.htm#i14325| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1305 | 1,5 |

| Marriage* | between 24 July 1326 and 23 March 1327 | Principal=Elizabeth Comyn1,6,7,8 |

| Death* | 23 October 1356 | 1,6 |

| Burial* | Flanesford Priory, Herefordshire, England7 | |

| DNB* | Talbot, Richard, second Lord Talbot (c.1306-1356), soldier and administrator, was the eldest son of Gilbert Talbot, the first Lord Talbot (1276-1346), a knight-banneret from Gloucestershire and Herefordshire, and an unknown mother. One of that company of young knights and bannerets who surrounded Edward III during the years of his greatest victories, Talbot fought in Scotland and France, served in the king's household, and presided as a justice. Earlier, in 1321–2, he joined the contrariants' uprising against Edward II. Said to have been dispatched with his brother Gilbert by the bishop of Hereford, Adam Orleton, to bolster Roger Mortimer's forces, Talbot was captured at Boroughbridge with his father on 16 March, when he was styled ‘bachelor’. Like his father he served in Gascony in 1324–5. With the overthrow of Edward II in 1326–7, Talbot's fortunes dramatically improved. Some time before February 1327 he married Elizabeth Comyn, sister and coheir of John Comyn of Badenoch (d. 1314), the possessor of a plausible claim to the Scottish throne, and a daughter and coheir of Joan, sister of Aymer de Valence, earl of Pembroke. When Aymer died on 23 June 1324 his estate was to be divided among the descendants of his sisters, Joan and Isabel. Elizabeth was potentially a very wealthy woman and thus attracted the notice of the grasping Despensers. On Aymer's death they imprisoned her and then moved her from castle to castle, until, on 20 April 1325, she granted Hugh Despenser the elder the manor of Painswick, Gloucestershire, and Hugh the younger Castle Goodrich, Herefordshire. She was also forced to acknowledge a debt of £20,000 and was apparently kept imprisoned until the Despensers were executed in 1326. After their marriage Talbot and Elizabeth embarked on a successful campaign to recover her portion of the Pembroke and Comyn estates. In 1330 Talbot and his father, Gilbert, were both summoned to royal councils, and in 1331–2 Talbot was named one of the keepers of Ireland, beginning two decades of intense service. Like his father he was summoned to parliament for the first time in January 1332 and, on 21 March, was named a keeper of the peace in Gloucestershire. Because of Elizabeth's claim to the Comyn lands in Scotland, which had been confiscated by Robert I for Comyn's support of England, Talbot counted himself among the disinherited who rallied to support Edward Balliol's claim to the throne of Scotland in 1332. In July Talbot joined the invasion of Scotland and was present at the battle of Dupplin Moor on 12 August; in recognition of his support Balliol named him lord of Mar and summoned him to a parliament at Edinburgh on 10 February 1334. That summer, however, the Scots rebelled against Balliol. Fleeing the insurrection, Talbot was captured on 8 September and ransomed a year later for about 2000 marks. In 1336 he was again named to a Gloucestershire peace commission, and in December 1337 became keeper of the town of Berwick and justiciar of the English lands in Scotland. He held that position until April 1340 but in February and March 1339 was keeper of Southampton, responsible for garrisoning the town. According to Froissart Talbot was at the unsuccessful siege of Tournai in September 1339. During the 1340s Talbot continued to divide his time between military and domestic service, sometimes serving with his father. They were commissioned to make arrests in Wales in 1340, were appointed justices of oyer and terminer in Shropshire and Staffordshire in February 1341, and in 1344 sat as justices in Wales. In May 1341 Richard Talbot became the chief justice on a trailbaston commission for the counties of Gloucester, Worcester, and Hereford, which sat on and off through 1343, and presided as a justice in Oxfordshire in 1344–5. In the summer of 1342, however, he fought as a captain of the English forces under William de Bohun at the battle of Morlaix in Brittany, where he captured Geoffroi de Charney. Recognizing his valuable services, Edward appointed Talbot steward of the household in May 1345, in which office he served for four years. In the spring of 1346 he was on another trailbaston commission in Worcestershire and, as steward, investigated accusations against the king's purveyors in several counties. That summer he embarked with Edward for France, where he was wounded during the campaign leading up to Crécy, although he was with the king at the battle and later at the siege of Calais. Talbot continued this brisk pace of military and judicial service through the last decade of his life. He sat on several commissions of oyer and terminer, some dealing with trespasses in the royal households. Once again he served on local peace commissions: in the counties of Oxford and Worcester in 1348 and 1353 and in Gloucester and Hereford in 1351, which included enforcement of the Statute of Labourers. While still steward he was a member of the great council in 1348. Between 1348 and 1351 he had custody of Pembroke during the minority of the heir to the earldom. In 1349 he served on a commission to halt the smuggling of uncustomed wool from England into Flanders. As a result of his faithful service he reaped impressive awards, including wardships, marriages, cash, and pardons of debts. He also had some setbacks, losing the castles of Blaenllyfni and Bwlchydinas which he claimed had been granted to his father in fee. In 1343 the papacy gave him permission to found an Augustinian priory at Flanesford, Herefordshire. Talbot died between 23 and 26 October 1356. His lands, most of which were of Elizabeth's inheritance and had been settled jointly on themselves or feoffees, passed to his son and heir, Gilbert, who was aged between twenty-five and thirty. Elizabeth remarried and survived until 1372. Scott L. Waugh Sources GEC, Peerage · F. Palgrave, ed., The parliamentary writs and writs of military summons, 2 vols. in 4 (1827–34) · RotP · Chancery records · Rymer, Foedera · Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke, ed. E. M. Thompson (1889) · Œuvres de Froissart: chroniques, ed. K. de Lettenhove, 25 vols. (Brussels, 1867–77) · Scalacronica, by Sir Thomas Gray of Heton, knight: a chronical of England and Scotland from AD MLXVI to AD MCCCLXII, ed. J. Stevenson, Maitland Club, 40 (1836) · Chronicon Henrici Knighton, vel Cnitthon, monachi Leycestrensis, ed. J. R. Lumby, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 92 (1889–95) · The ‘Original chronicle’ of Andrew of Wyntoun, ed. F. J. Amours, 6 vols., STS, 1st ser., 50, 53–4, 56–7, 63 (1903–14) · Adae Murimuth continuatio chronicarum. Robertus de Avesbury de gestis mirabilibus regis Edwardi tertii, ed. E. M. Thompson, Rolls Series, 93 (1889) · W. Stubbs, ed., Chronicles of the reigns of Edward I and Edward II, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 76 (1882–3), esp. Annales Paulini, Gesta Edwardi de Carnarvon, Vita et mors Edward II · Justices Itinerant, PRO, Just1/1388 · J. R. S. Phillips, Aymer de Valence, earl of Pembroke, 1307–1324: baronial politics in the reign of Edward II (1972), 2, 15, 24, 235 · N. Fryde, The tyranny and fall of Edward II, 1321–1326 (1979), 114–15, 230, 253 · N. Saul, Knights and esquires: the Gloucestershire gentry in the fourteenth century (1981), 79, 123, 173, 276, 281 · P. Chaplais, ed., The War of Saint-Sardos (1323–1325): Gascon correspondence and diplomatic documents, CS, 3rd ser., 87 (1954), 240, no. 1 · R. A. Griffiths and R. S. Thomas, The principality of Wales in the later middle ages: the structure and personnel of government, 1: South Wales, 1277–1536 (1972), 26 · R. Nicholson, Edward III and the Scots: the formative years of a military career, 1327–1335 (1965), 66, 73, 80, 152, 158, 159–61, 163, 168–9, 172, 185 · Tout, Admin. hist. · W. Rees, ed., Calendar of ancient petitions relating to Wales (1975), 274–5, 493–4 · G. Wrottesley, Crécy and Calais (1897); repr. (1898) · CIPM, 8, no. 714; 10, no. 326 · CPR, 1327–1330, 1350–54 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Scott L. Waugh, ‘Talbot, Richard, second Lord Talbot (c.1306-1356)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/26938, accessed 23 Sept 2005] Richard Talbot (c.1306-1356): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/269389 | |

| Event-Misc* | 13 March 1322 | Battle of Boroughbridge, was taken in arms against the King with his father.5 |

| Event-Misc | 14 April 1329 | had letters of protection, being ready to cross the sea with the King.5 |

| Event-Misc | between 27 January 1332 and 20 September 1355 | summoned to parliament by writ directed Ricardo Talbot5 |

| Event-Misc | 12 August 1332 | Dupplin Moor, Scone, Scotland, joined Edward Balliol in his invasion of Scotland, contrary to the King's orders, and was present at the defeat of the Scots by the "disinherited lords" at Dupplin Moor .5 |

| Event-Misc | 10 February 1334 | Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland, sat as "dominus de Mar" in the Parliament held by Edward balliol and, as such, witnessed the treat of Newcastle, whereby Balliol surrendered Berwick, Roxburgh, etc, to Edward III, having previously received of Balliol a conditional grant of Kildrummy Castle, Aberdeen, 17 Feb.5 |

| Event-Misc | September 1334 | Linlithgow, Scotland, was captured by the Scots and impresoned at Dumbarton; but after leaving hostages for his ransom of £2000, was brough south to the Marches under safe conduct from Edward III (2 Apr 1335).5 |

| Event-Misc | 21 December 1337 | Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland, England, Keeper of Berwick-upon-Tweed and Justiciar of the lands in Scotland occupied by the King of England.5 |

| Event-Misc | 23 February 1340 | Southampton, Hampshire, England, He was appointed keeper of Southampton.7 |

| Event-Misc | July 1340 | Tournay, France, He served at the siege of Tournay.7 |

| Event-Misc | 30 September 1342 | Morlaix, France, He was a captain in the army of Sir William de Bohun which defeated Charles of Blois at Morlaix, when he took prisoner Geoffrey de Charny, one of the French leaders, and sent him to his castle at Goodrich, Hereford., Witness=Sir William de Bohun K.G.7 |

| Event-Misc | May 1345 | He was Steward of the King's household.7 |

| Event-Misc | 26 August 1346 | Although wounded earlier near the Seine, he was with the King at the battle of Crecy and at Calais.7 |

| Event-Misc | 18 December 1346 | Flanesford Priory, Herefordshire, England, He had a license to found the priory of Austin Canons at Flanesford within the Lordship of Castle Goodrich.7 |

| Title* | 2nd Lord Talbot5 |

Family | Elizabeth Comyn b. 1 Nov 1299, d. 20 Nov 1372 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 95-31.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 84A-30.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 5, p. 3.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 242.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 612.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-5.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 613.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 10.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

Elizabeth Comyn1

F, #2719, b. 1 November 1299, d. 20 November 1372

|

| Father* | John Comyn d. 10 Feb 1306; 2nd Daughter and co-heir2,3,4,5 | |

| Mother* | Joan de Valence2,4 | |

Elizabeth Comyn|b. 1 Nov 1299\nd. 20 Nov 1372|p91.htm#i2719|John Comyn|d. 10 Feb 1306|p91.htm#i2720|Joan de Valence||p91.htm#i2721|Sir John Comyn|d. c 1303|p91.htm#i2723|Eleanor de Baliol||p91.htm#i2724|Sir William de Valence|b. c 1226\nd. b 18 May 1296|p91.htm#i2722|Joan de Munchensi|d. b 21 Sep 1307|p365.htm#i10939| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | 1 November 1299 | 1,6,4 |

| Marriage* | between 24 July 1326 and 23 March 1327 | Principal=Sir Richard Talbot M.P.1,6,7,5 |

| Marriage* | between 21 February 1358 and 16 February 1361 | Principal=Sir John Bromwych4 |

| Death* | 20 November 1372 | 1,4 |

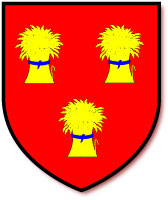

| Arms* | between 1322 and 1326 | Goodrich Castle, Hereford, England, Sealed: Three Garbs (Birch).8 |

Family | Sir Richard Talbot M.P. b. c 1305, d. 23 Oct 1356 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 30 Aug 2004 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 95-31.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 95-30.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-4.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 614.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 10.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-5.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 613.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-6.

John Comyn1

John Comyn1

M, #2720, d. 10 February 1306

| Father* | Sir John Comyn2,3 d. c 1303 | |

| Mother* | Eleanor de Baliol2,4 | |

John Comyn|d. 10 Feb 1306|p91.htm#i2720|Sir John Comyn|d. c 1303|p91.htm#i2723|Eleanor de Baliol||p91.htm#i2724|Sir John Comyn|d. a 1273|p365.htm#i10940|Amabilia (?)||p365.htm#i10941|Sir John de Baliol|d. 27 Oct 1268|p91.htm#i2725|Devorguilla of Galloway|d. 28 Jan 1289/90|p91.htm#i2726| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Principal=Joan de Valence1,5,6,7 | |

| Death* | 10 February 1306 | Church of the Grey Friars, Dumfries, Scotland, Murdered by Robert the Bruce1,5,8 |

| Death | 5 April 1306 | Church of the Grey Friars, Dumfries, Scotland, He was murdered by Robert the Bruce.3 |

| DNB* | Comyn, Sir John, lord of Badenoch (d. 1306), magnate, was the son and heir of John Comyn, known as the Competitor (d. c.1302), and his wife, Eleanor (Marjory in Scottish sources), sister of John de Balliol, later king of Scots. He married Joan de Valence, daughter of William de Valence, earl of Pembroke (d. 1296), a cousin of Edward I, and had three children—John (d. 1314), Elizabeth (married Richard Talbot), and Joan (married David, earl of Atholl). He was known as ‘the younger’ or ‘the son’ until he inherited his father's extensive estates—the last reference to him as ‘the son’ appears to have been in 1301. He was made a knight by King John (de Balliol) probably soon after 1292. John Comyn had received the gift of the important manors of Walwick, Thornton, and Henshaw in Tynedale by c.1295 but on his father's death he inherited wide-ranging and vast estates in the Scottish highlands (Badenoch and Lochaber), in Roxburghshire (Bedrule and Scraesburgh), in Dumfriesshire (Dalswinton), in Perthshire (Findogask and Ochtertyre), in the Clyde valley (Machan), in Dunbartonshire (Lenzie and Kirkintilloch), and in Atholl. Lands in England included important estates in Tynedale (Tarset and Thornton) and Lincolnshire (Ulseby). The castles of Lochindorb, Ruthven, Inverlochy, and Blair Atholl made a formidable defence to his power in northern Scotland, while the castle of Dalswinton, and probable castle sites at Machan and Kirkintilloch, added weight to his influence further south. Apart from this substantial landed base, John Comyn inherited powerful family support and a long tradition of involvement at the centre of Scottish politics. His family links—John Comyn, earl of Buchan (d. 1308), who dominated north-east Scotland, was his cousin, King John was his uncle, and William, earl of Pembroke, was his brother-in-law—had a significant influence on his key role at the forefront of Scottish political affairs from 1296 to 1306. As a relative of John de Balliol, and one of the leading supporters of his kingship, John Comyn the younger took a prominent role when open rebellion broke out in Scotland against English overlordship in 1296. On 26 March, with seven Scottish earls, he crossed the Solway from Annandale (which had been given to him by King John), burning villages to the suburbs of Carlisle itself before trying unsuccessfully to take the city by storm. He was also present when Hexham Priory was burnt two weeks later, before retreating northwards on news of Edward I's imminent arrival, and he helped to capture Dunbar Castle on 22 April. However, this castle was forced to surrender to Edward I on the 28th, John Comyn having been handed over as a hostage to the English king on the previous day. His wife, Joan, was already in England, having been given letters of safe conduct to go to London as soon as her husband came out in open rebellion. In September 1296 she was given lands worth 200 marks in Tynedale for her support. Along with other Scottish nobles taken into captivity at Dunbar, John Comyn was taken to England where he became a prisoner at the Tower of London. In 1297 he promised to go with the king overseas, and to serve him well and faithfully against the king of France, but by 1298 he was back in Scotland. The years 1296 to 1298 had been significant for the Badenoch branch of the family. Not only did they have their valuable Northumberland lands confiscated, but the Comyn leadership of the Scottish political community, little challenged since the mid-thirteenth century, no longer went unquestioned after the enforced absence of the chief members of the family from 1296 to 1298. James Stewart (d. 1309), Bishop Robert Wishart (d. 1316), and William Wallace (d. 1305) came to the fore in these years, and Wallace became sole guardian early in 1298. By then John Comyn was once more in opposition to Edward I, as is indicated by the English king's peremptory command on 26 March of that year to Comyn's wife, Joan, to come to London with her children without delay. After the defeat of an English army at Stirling Bridge by William Wallace and Andrew Murray (d. 1297) on 11 September 1297, Edward I had taken the Scottish threat more seriously. He set up headquarters at York in the summer of 1298, and on 22 July defeated the Scots at the battle of Falkirk. John Comyn probably contributed cavalry to the Scottish forces, led by Wallace. According to the fourteenth-century Scottish historian John Fordun, Wallace's defeat was caused by the flight of the cavalry, and he blamed the Comyns for this. However, it is more probable that panic rather than cowardice was the cause of defeat, and it seems unlikely that the Comyns were blamed at the time. Following his defeat, Wallace resigned as guardian, and between July and December 1298 John Comyn the younger and Robert Bruce, earl of Carrick, the future king, were elected joint guardians of Scotland. It is possible that there had been tension between the Comyns and Wallace, who had risen to prominence in their absence. And there was certainly tension between John Comyn and Robert Bruce, probably resulting from the Bruce claim to the Scottish crown, and the strong Comyn championing of Balliol's kingship, during the Great Cause. These resentments came into the open at a council held at Peebles on 19 August 1299, when an argument over claims to William Wallace's lands led to a brawl between Comyn and Bruce supporters, in the course of which ‘John Comyn leaped at the earl of Carrick and seized him by the throat’ (Barrow, 107). The bishop of St Andrews, William Lamberton (d. 1328), was elected as guardian alongside Comyn and Bruce to help preserve unity in government, but this unity lasted only until May 1300, when Bruce was forced from office. At a parliament held in Rutherglen on 10 May, Comyn argued with Lamberton, saying that he would no longer serve with him. Another reorganization of the guardianship led to the preservation of unity with Comyn and Lamberton remaining in office, but being joined by Sir Ingram de Umfraville, an ally of the Comyns and Balliol's kinsman. This alliance appears to have dissolved between December 1300 and May 1301, with John Soulis (d. c.1310) appearing as sole guardian at that time. It seems, from official record sources, that Comyn resigned for a short time, although, according to John Fordun, John Comyn remained in office continuously from 1298 to 1304, with John Soulis being associated with the guardianship by John de Balliol's express wish in 1301 and 1302. John Comyn was sole guardian in the autumn of 1302, however, when Soulis went with an embassy to France. Early in 1303 Comyn's leadership of the Scottish political community was again apparent, since on 24 February he was ‘leader and captain’ of the Scottish army which defeated an English force at Roslin. After this victory the Scots, led by Comyn, described by the chronicler Bower as chief guardian of Scotland, and Simon Fraser (d. 1305), harassed the English king's officers as well as the English king's supporters in southern Scotland. They were still active in the autumn of 1303 when they raised Lennox, causing Margaret, countess of Lennox, to ask Edward I's help against John Comyn. Edward's retaliation had already started in the summer of 1303. He marched north to assert English authority, and in October 1303 stayed for a while at Lochindorb, a castle at the heart of John Comyn's northern power base. A combination of the peace made between France, hitherto Scotland's ally, and England on 20 May 1303, and the realization that the Scots could not muster an army big enough to match the English in pitched battle, led to all the leading Scottish magnates, except William Wallace, Simon Fraser, and John Soulis, submitting to Edward I on 9 February 1304. John Comyn, no doubt in his capacity as sole guardian, negotiated conditions for surrender on behalf of the community of Scotland. Negotiations had begun between the earl of Ulster, the royal commander in the west of Scotland, and Comyn on 6 February. Comyn refused to surrender unconditionally. He demanded firstly an amnesty and restoration of estates for those who had fought against Edward, and secondly that the Scottish people should be ‘protected in all their laws, customs and liberties in every particular as they existed in the time of King Alexander III’ (Barrow, 130). There was no disinheritance, but not all of Comyn's demands were met—the good old days of Alexander III could not be restored, and varying degrees of exile were imposed on the leading men. Robert Wishart, bishop of Glasgow, for instance, was initially required to leave Scotland for two to three years; in addition, John Comyn, Alexander Lindsay, David Graham, and Simon Fraser were ordered to capture William Wallace and hand him over to Edward. Edward I took over the government of Scotland, appointing his nephew, John of Brittany (d. 1334), as lieutenant of Scotland. John Comyn was one of a council of twenty-two Scots (including Robert Bruce) appointed to advise the new lieutenant. The savage execution of William Wallace on 23 August 1305 may have raised the level of indignation in Scotland at English overlordship. This forms the background to the infamous murder of John Comyn by Robert Bruce in the Greyfriars Church at Dumfries on 10 February 1306 and Robert Bruce's inauguration as king of Scots six weeks later. According to tradition, first recounted by Scottish chroniclers of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Bruce and Comyn, rivals and the two most powerful nobles in Scotland, made an agreement that Bruce should take the Scottish crown and Comyn should take Bruce's lands in return. Comyn, however, betrayed Bruce and told Edward I of Bruce's plans. After being confronted with his treachery in the church at Dumfries, Comyn quarrelled with Bruce and was murdered along with his uncle, Robert. More contemporary, though still biased, English accounts give a different angle to the murder, and the narrative of Walter of Guisborough deserves some precedence. According to Guisborough, Bruce feared that Comyn would hinder him in his attempt to gain the Scottish crown, and sent two of his brothers, Thomas and Nigel, from his own castle at Lochmaben to Comyn's castle at Dalswinton, 10 miles away, asking Comyn to meet him at the Greyfriars Church, Dumfries, to discuss ‘certain business’. It seemed that Bruce wanted to put a plan to Comyn, no doubt involving the revival of Scottish kingship with Bruce on the throne. After initially friendly words, Bruce turned on Comyn and accused him of treacherously reporting to Edward I that he, Bruce, was plotting against him. It seems probable that their bitter antagonisms of the past were instantly revived and that in a heated argument mutual charges of treachery were made. Bruce struck Comyn with a dagger and his men attacked him with swords. Mortally wounded, Comyn was left for dead. Comyn's uncle, Robert, was killed by Christopher Seton (d. 1306) as he tried to defend his nephew. According to tradition in both Scotland and England, John Comyn was killed in two stages, with Bruce's men returning to the church to finish off the deed. According to Bower, Bruce returned to Lochmaben Castle and reported to his kinsmen James Lindsay and Roger Kirkpatrick ‘I think I have killed John the Red Comyn’ (Bower, 6.311). Bruce's men returned to the church to make sure that the deed was done, with Roger Kirkpatrick, according to a wholly fabulous tale, exclaiming ‘I mak siccar’. What is clear is that Comyn's rivalry with Bruce must have been intense since 1286. The Comyns had suppressed Bruce rebellions in 1286 and 1287, and were strong supporters both of John de Balliol's candidature for the Scottish crown in the Great Cause, 1291–2, and of Balliol's kingship after 1292. John Comyn represented a long tradition of Comyn leadership of the Scottish political community during most of the thirteenth century. He was a major obstacle to Robert Bruce's ambitions, especially as he could make a double claim to the Scottish crown himself, as heir to John de Balliol as well as in his own right. Contemporary English sources like Guisborough emphasize John Comyn's refusal to support Robert Bruce's treachery by overturning the lawful sovereign, Balliol. The importance of John Comyn's murder was soon recognized in both Scotland and England. Edward I's initial response was phlegmatic, but by 5 April he had appointed Aymer de Valence (d. 1324), Comyn's brother-in-law, as his special lieutenant in Scotland with wide-ranging and drastic powers against Bruce and the alliance between the English and the remaining members of the Comyn family continued until the battle of Bannockburn in 1314. In Scotland, Bruce was forced to follow up the murder by destroying the Comyn power base in the north before being fully assured of his kingship. A civil war thus accompanied the Anglo-Scottish war. In 1306 Edward I ordered Joan de Valence to send her son, John, John Comyn's son and heir, to England where he was to be in the care of Sir John Weston, master and guardian of the royal children. His father's vast landholding was divided up among Bruce's supporters. This John Comyn lost his life, and any hope of retrieving the vast Scottish inheritance of the Comyns of Badenoch, at the battle of Bannockburn, when he fought on the side of Edward II. Alan Young Sources G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce and the community of the realm of Scotland, 3rd edn (1988) · N. Reid, ‘The kingless kingdom: the Scottish guardianships of 1286–1306’, SHR, 61 (1982), 105–29 · R. Nicholson, Scotland: the later middle ages (1974), vol. 2 of The Edinburgh history of Scotland, ed. G. Donaldson (1965–75) · W. Bower, Scotichronicon, ed. D. E. R. Watt and others, new edn, 9 vols. (1987–98), vol. 6 · CDS, vol. 2 · The chronicle of Walter of Guisborough, ed. H. Rothwell, CS, 3rd ser., 89 (1957) · J. Stevenson, ed., Chronicon de Lanercost, 1201–1346, Bannatyne Club, 65 (1839) · J. Barbour, The Bruce, ed. W. W. Skeat, 2 vols., STS, 31–3 (1894) · Scalacronica, by Sir Thomas Gray of Heton, knight: a chronical of England and Scotland from AD MLXVI to AD MCCCLXII, ed. J. Stevenson, Maitland Club, 40 (1836) · Johannis de Fordun Chronica gentis Scotorum / John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish nation, ed. W. F. Skene, trans. F. J. H. Skene, 2 vols. (1871–2) © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Alan Young, ‘Comyn, Sir John, lord of Badenoch (d. 1306)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/6046, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Sir John Comyn (d. 1306): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/60469 | |

| Name Variation | The Red Comyn1,5 | |

| Event-Misc | March 1296 | He was one of the leaders of a Scottish Army which raided Cumberland8 |

| Event-Misc* | 27 April 1296 | He was captured at Dunbar and sent to the Tower of London.3,8 |

| Event-Misc | 30 July 1297 | John Comyn was released after giving his son John as hostage., Principal=Sir John Comyn3,8 |

| Event-Misc | 19 August 1299 | Peebles, At a meeting with other nobles he scuffled with Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, and seized the Bruce by the throat. It was agreed that Comyn should be one of three guardians of the Kingdom.8 |

| Event-Misc | 24 February 1302/3 | Rosslyn, He defeated the English8 |

| Event-Misc* | 9 February 1303/4 | Comyn was defeated by Edward I at Strathord, and was banished unless he would deliver William Waleys, Principal=Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England8 |

| Event-Misc | October 1305 | The fines for his rebellion were reduced to three years' rental from his estate.8 |

| Title* | Lord of Badenoch1,5 | |

| HTML* | Clan Comyn The Clan Comyn (Cumming) John Comyn Electric Scotland |

Family | Joan de Valence | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 95-30.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 95-29.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 231.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-3.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-4.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 614.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 5, p. 91.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 64.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 232.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 10.

Joan de Valence1

F, #2721

| Father* | Sir William de Valence1,2,3 b. c 1226, d. b 18 May 1296 | |

| Mother* | Joan de Munchensi4 d. b 21 Sep 1307 | |

Joan de Valence||p91.htm#i2721|Sir William de Valence|b. c 1226\nd. b 18 May 1296|p91.htm#i2722|Joan de Munchensi|d. b 21 Sep 1307|p365.htm#i10939|Hugh X. of Lusignan|b. b 1196\nd. a 6 Jun 1249|p97.htm#i2883|Isabella of Angoulême|b. 1188\nd. 31 May 1246|p55.htm#i1621|Sir Warin de Munchensi|d. c 20 Jul 1255|p231.htm#i6906|Joan Marshall|b. c 1204\nd. b Nov 1234|p227.htm#i6804| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Principal=John Comyn1,5,3,6 |

Family | John Comyn d. 10 Feb 1306 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 4 Nov 2004 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 95-30.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 148-3.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 614.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 154-29.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-4.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 5, p. 91.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 232.

Sir William de Valence1

Sir William de Valence1

M, #2722, b. circa 1226, d. before 18 May 1296

|

| Father* | Hugh X of Lusignan2,3,4,5 b. b 1196, d. a 6 Jun 1249 | |

| Mother* | Isabella of Angoulême2,6 b. 1188, d. 31 May 1246 | |

Sir William de Valence|b. c 1226\nd. b 18 May 1296|p91.htm#i2722|Hugh X of Lusignan|b. b 1196\nd. a 6 Jun 1249|p97.htm#i2883|Isabella of Angoulême|b. 1188\nd. 31 May 1246|p55.htm#i1621|Hughes le Brun (?)|d. 5 Nov 1219|p144.htm#i4303|Agatha de Preuilly||p461.htm#i13816|Count Aymer de Valence of Angoulême|b. b 1165\nd. 1218|p97.htm#i2884|Alice de Courtenay|b. c 1160\nd. c 14 Sep 1205|p97.htm#i2885| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Burial* | Westminster Abbey, London, England2 | |

| Birth* | circa 1226 | 3,4 |

| Marriage* | 13 August 1247 | Principal=Joan de Munchensi7,4 |

| Death* | before 18 May 1296 | 4 |

| Inquisition Post Mor | 24 May 1296 | he held Manors of Dunham, Notts., Geynesburgh, Lincos., Waddone, Glou., Bampton, Oxon., Inteberne, Worc., Cumptone-Pundelarch, Dors., Ixning, Kentewell, Roydon, and Wrydelington, Suff., and Nyweton, Hants., mess. and lands at Gt., Lit., and Pont-Eyland, Merdesfen, and Calverdon, Northumb., Chardesly, Bucks., and in Co.'s Wexford and Kilkenny, with Goodrich Castle, Here., and leaving s. h. Ayer, 21-8.8 |

| Burial | Westminster Abbey, Westminster, Middlesex, England5 | |